Source: Rebel Notes

The fascists were beaten back in the 1930s but they have returned with new names, new flags; Britain First, English Defence League, The Football lads Alliance…

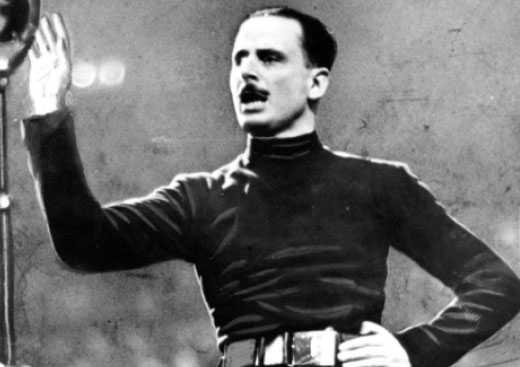

A long neglected piece of radical working class and anti-fascist history was movingly celebrated at a ceremony in the Market Square of Stockton on 9 September 2018. In September 1933, it was one of several small towns in the North East of England devastated by the economic depression that was targeted by Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists for recruitment to his street army and political project. The 30 or so members of the fascists resident in Stockton were joined by 100 more drawn from other northern towns and cities. They planned to march along the high street and then rally in the Market Square by the Town Hall. Local anti-fascists had got wind of this but the police hadn’t. Barely a handful of police were present when the BUF were ambushed by more than 2,000 anti-fascists drawn from the Communist Party, Independent Labour Party, National Unemployed Workers Movement, Labour Party and trade unions. It was a violent clash. The BUF rally was closed down and their activists chased out of the town.

A plaque was unveiled on 9 September by Stockton’s mayor in that same Market Square, who spoke of her pride as a trade unionist in the anti-fascist spirit of resistance that day. She was one of several platform speakers, which included local MP Alex Cunningham, Jude Kirton-Darling an MEP for the North East region and granddaughter of a Czech-born Holocaust survivor, and Marlene Sidaway, of the International Brigade Memorial Trust, born locally, whose late husband fought against fascism in the Spanish Civil War.

A plaque was unveiled on 9 September by Stockton’s mayor in that same Market Square, who spoke of her pride as a trade unionist in the anti-fascist spirit of resistance that day. She was one of several platform speakers, which included local MP Alex Cunningham, Jude Kirton-Darling an MEP for the North East region and granddaughter of a Czech-born Holocaust survivor, and Marlene Sidaway, of the International Brigade Memorial Trust, born locally, whose late husband fought against fascism in the Spanish Civil War.

This was David Rosenberg’s speech.

I am so honoured to be here for this commemoration of the people of Stockton who understood so early on the danger posed by Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists and showed by their collective action that they had no use for fascism.Mosley could only hope to build a movement at a time of crisis and the key to that crisis was unemployment. In 1929 Britain’s unemployment reached an unprecedented total of 1.5 million. 2 years later doubled 3 million – 20% of the workers nationally, but we know it was not evenly spread. Everywhere was hit badly, but nowhere worse than the northeast where in some parts it 80% of the workforce were out of work.

In October 1932, the same month that Mosley created the British Union of Fascists, there was a conference in East London about unemployment, organised by father Groser, an Australian born Anglo-Catholic priest, who studied theology in Yorkshire and would go on to play a key part in the anti-fascist movement. In his earlier days Father Groser acknowledged that his political ideas were conservative and imperialist. All that changed with his first placement – in a slum parish in Newcastle. And everything he learnt in Newcastle about supporting the poorest people, he brought with him to London’s East End.

In his conference invitation Groser described the effects of long-term unemployment: “physical depression, ill-health, frustration of personality, the loss of proper self-respect, which created an embittered and hopeless section of the community.”

People devoid of hope were ripe for receiving fascist messages that promised to make them feel good about themselves and their country again. Mosley denounced the political system of democracy that, he said, had created the crisis and given us the tired old gang of politicians who could not navigate their way out of it. He promised strong and effective government unencumbered, as he put it, by a daily opposition.

Like other fascist leaders in Europe – he portrayed himself as a saviour and redeemer who would fight for the disempowered and disenfranchised, and make the country great again. The day his party was formed he launched a book called The Greater Britain, but it was really about the greater Mosley.

He made a special appeal to youth, saying his party alone would offer young people a chance to serve their country in times of peace, not just as fodder in times of war. he promised a party of action that would mobilise energy, vitality and manhood to save and rebuild the nation.

Between 1932-34 the BUF built a national infrastructure of 500 branches and that included fascist groups in Newcastle, Sunderland, Gateshead, Durham and here in Stockton.

In the North East and in south Wales, Mosley’s movement made an appeal to miners; in Lancashire they sought support from Cotton workers, in south-west England it was farmers. In many small towns Mosley sought support from small shopkeepers and the lower middle class. He appealed to the unemployed, especially those who served in wartime but were now on the scrapheap.

In London, by contrast, he sought out the wealthy and powerful. In late 1933, three months after the events in Stockton, that he won the support of one of the most powerful people in the land, Lord Rothermere – the publisher of the most widely read newspaper in Britain the Daily Mail.

Unlike other political movements who tried to capture town halls and parliament they tried to capture the street. Mosley told his followers that they were invincible, that the streets belong to them, and that is why the courageous actions of people in Stockton were important.

You recognised what his movement was about very early on and showed that Blackshirts were not welcome here. Other parts of the country took longer to wake up to the menace of fascism. They thought Mosley had something to offer.

In London in 1934 he held a huge rally in London’s Olympia Exhibition Centre. It was packed with 15,000 people. Among them were 150 members of parliament looking for inspiration. Members of the House of Lords came in Blackshirts. They had already been inspired. But there were also protesters – thousands of them outside the venue – mobilised by the Communist Party and the Independent Labour Party, but also protesters inside, who obtained tickets in an interesting way. The Daily Mail ran a competition and you could win £1 and a ticket to a Mosley rally if your letter was published in the Daily Mail but for the purposes of this competition your letter had to begin with the words: “why I like the Blackshirts”. Anti-fascists wrote spoof letters, got tickets and forged more.

When Mosley walked up to the platform through a guard of honour with a spotlight on him he had no idea demonstrators were inside as well as outside, but he had 1,000 uniformed, jackbooted, stewards, just in case.

Just three minutes into his speech a protester stood up and shouted “Down with Mussolini, down with Hitler, down with Mosley, fascism means hunger and war” and sat down again. Every three minutes a protester stood up with a similar heckle, until Mosley gave a sign. The next time it happened the heckler was yanked out of their seat by 15 fascists who beat the living daylights out of him in front of everyone Mosley wanted to impress. It was a chaotic and violent evening – 80 protesters needed hospital treatment. And amid the violence, Mosley made his most anti-Semitic speech to date.

It needed both a physical and ideological response. Stockton had shown the way in terms of a physical response. That was repeated in three other northern towns – Liverpool Manchester and Leeds. But the biggest confrontation would come in October 1936 in London’s East End, when a march and show of strength by 4,000 fascists, protected by 7,000 police, was stopped by around 200,000 people taking to the streets mounting a mass blockade of the streets the fascists wanted to march through then putting up barricades in Cable Street the alternative route.

In Cable Street two remarkable things took place. The first two-thirds of Cable Street was mainly Jewish the last third mainly Irish. Two poor communities bordering each other. Mosley tried to win Irish catholics against their Jewish neighbours. The anti-fascists had tried to unite both communities against the fascists. On the day Irish people came from their end of Cable Street to help Jews building barricades against the fascists.

The second remarkable thing – the first barricade was a truck on its side. The police could not see beyond it, but other barricades were built behind reinforced with furniture. Eventually the police dislodged enough of the first barricade to run through and check if they had a clear path, but they got stuck between that barricade and the next one. Women in flats above the shops saw this, picked up everything to hand in their kitchens, and rained down on the police. With resistance from above and at ground level they had to retreat and tell Mosley he could not march.

1930s rent strike

Stockton was a battle, Cable Street was a battle, but the war against fascism in 1930s Britain was ultimately won on housing estates, especially in East End, where anti-fascists helped to set up tenants defence committees to bring the communities that Mosley had tried to divide with hate – the Jewish and the Irish – into a common fight for better housing. The unity and solidarity they forged made it much harder for the fascists to get a hearing among them.

In an age of plenty when each person felt secure and valued and none experienced pangs of hunger and resentment, Mosley’s malicious sentiments would have floated away with the wind. The beliefs of his movement could only manipulate people’s consciousness when there was profound and pernicious social inequality, in a society beset my mass unemployment, low pay, poor housing, poor access to education, neglect by those with power and wealth, a widespread hopelessness, and a longing for personal and national salvation. Such problems though are not confined to the past.

The fascists were beaten back in the 1930s but they have returned with new names, new flags; Britain First, English Defence League, The Football lads Alliance, National Action… If we are to stay true to the traditions of resistance established in Stockton and in Cable Street we must stand not just against fascism but every manifestation of racism and authoritarianism that feeds it, and work to strengthen an anti-racist and anti-fascist majority in our society. No Pasaran! They shall not pass!

The Young’uns – The Battle Of Stockton (Live)

Two of the award-winning group the Young’Uns are from Stockton. Their song, The Battle of Stockton, is dedicated to their grandfathers who said no to Mosley’s fascists.