It is shocking how little people know about how their clothes are made and the inhumanity of the fashion industry.

Slave to Fashion is the latest book by Safia Minney, and is made up of interviews and micro-documentaries with the men, women and children caught in slavery, making the clothes sold on our high streets, in Europe and the developing world. She is interviewed by Tansy Hoskins, author of Stitched Up: The Anti-Capitalist Book of Fashion.

What made you want to write this book?

When I founded ethical clothing brand People Tree over 20 years ago, I was shocked at how inhumane the fashion industry is and how little people know about how their clothes are made. I regularly visited and supported labour unions to learn about conventional fashion business and how Fair Trade fashion needed to be different. We developed the first Fair Trade standards for fair trade, organic cotton growing and garment manufacture.

When the British government Included supply chains in the Modern Slavery Act at the end of 2015, it suddenly meant that companies with a £36mn sales turn over or more, would have to report on what they were doing to eradicate slavery in their supply chains. I was really excited! This is a window of opportunity and has the potential to create a level playing field where fashion companies make clothes with respect to workers and the environment. It could mean the end to poverty wages and paying bribes to avoid paying fines for ignoring human rights & labour & environmental law abuses.

It’s shocking that criminal gangs and brokers use poverty and lack of power to force women and children into further vulnerability and slavery. Over the years I commonly heard the stories from women forced into servitude, ‘sold’ by their families and forced to accept the sexual advances by their male bosses and silenced by the fear of their children going hungry.

Fair Trade companies have proven partnership with their suppliers work and they have built systems of transparency and accountability. The Modern Slavery Act gives us a chance to move all businesses and Boards to do business to legal norms and deliver human rights for their workers, social equity and hopefully realign our economic systems within our planets limited resources.

Who was the audience you had in mind when you were writing it?

I hope Slave to Fashion will be easy to understand by anybody keen to learn more about fair trade, social justice, ethical fashion and new economics. I really wish that Fair Trade was taught in Geography as it was 10 years ago in most schools … good economics is everyone’s responsibility.

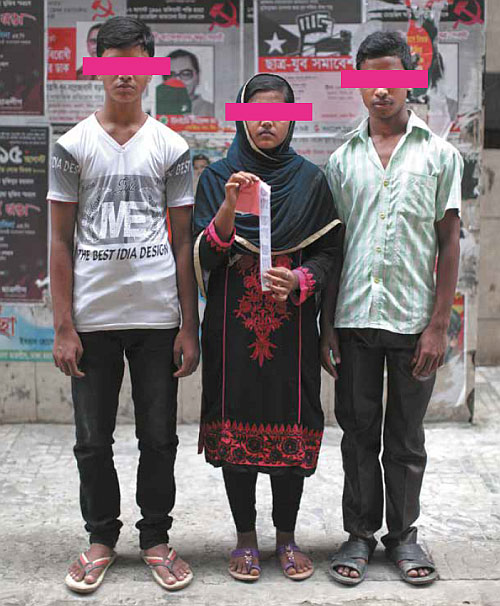

Three workers in a Bangladesh knitwear factory: Millat, aged 15, earns $38 a month. Nodi, 14, earns $66 a month. Mossaraf, 16, earns $44 a month

“Slave” is a very emotive and politically charged word, how have you defined slavery in the book?

Slave is an emotionally charged word and it is political too. It needs to be, slavery and exploitation is abhorrent. Slavery in my book means bonded, forced and child labour. It also covers human trafficking.

This book is full of interviews that will shock even people engaged in labour rights campaigns, were you shocked by what you found and are there any particular stories that have stayed with you?

The stories of people I met writing this book have all stayed with me. In particular the story of Seema in Delhi, India who faced regular sexual advances by her boss and who faced the choice of being assaulted or moving factory and losing all her employment benefits. Also the lovely children of 14 who make clothes for Europe and Japan who are happy to work but need the tea breaks, shorter working hours and a living wage. If only they had the right to belong to a union that would help protect them.

You have gone to great lengths to get first hand testimony from garment workers and bring much needed exposure to marginalised women’s voices. How important is this to you and why?

We hear too little from the workers themselves about what they want and need and what’s needed to empower people and communities. I wanted readers to hear from the people themselves. I founded the first ethical fashion brand to prove that another way of doing business is possible and I’m a campaigner.

Social dialogue and collaboration is key to holding businesses accountable and the ETI and other institutions are helping create a new way of doing business that In many ways copies the Fair Trade model. Today we also have tech companies to help unions and their members to get the word out and expose companies with Slavery and exploitation in their supply chains and help build strong local NGOs to enforce local laws. There are great campaigning organisations like CCC & I think we need to be more conscious as consumers. We need to be the voice of the voice less.

Why have you picked freedom of association and the living wage as the two things that most need to happen in the fashion industry? How can people support these aims?

After years of working in Bangladesh, India and other developing countries I think that working to pay a Living wages and Freedom of Association is the only way to bring workers the chance for a decent life, social justice and an equitable economy. These will eradicate slavery and the worst kinds of exploitation in fashion supply chains.

It also means that local associations can do what is needed to improve law enforcement locally. That’s important. Shoppers can buy from ethical brands, they can look out for labels that price this like WFTO, and they can ask their favourite brands what they are doing to eradicate modern slavery. They can write to their local MP too and ask for an ethical fashion manifesto. Baroness Lola Young is working on this now and the ethical fashion movement will support her.

In contrast to the subject mattered , Slave To Fashion is a beautiful looking book, that feels like a piece of art. What can you reveal about the design process? What can people taking on the fashion industry gain from great design?

I’ve never found that shocking topics are digestible or that they hold with a new audience unless they feel comfortable with the tool of communication. I’m glad of the format and graphics of STF make the subject matter easy to read. Hopefully that will stir the heart and make people promote awareness and act.

When I started People Tree in Japan 25 years ago, I knew if the product wasn’t of quality and beauty, people wouldn’t keep buying it. And to make Fair Trade work it relies on equal partnership and sustained trade. Making beautiful product respects the artisan and telling the story of slavery needs to respect the people caught in it.

I understand you had an interesting path to funding this project – what were the pros and cons of crowdfunding and would you recommend it?

Using Kickstarter to raise money to fund the research, photography and production of the book was brilliant. 500 people supported it and raised £38k. The project didn’t cover my work, but that’s OK – like all the best projects – it was a labour of LOVE!

Safia Minney is a pioneer in ethical business. She is the founder of Fair Trade and sustainable fashion label, People Tree. Slave to Fashion is published by New Internationalist Books.