Source: Infernal Machine

In framing the problem of the far-right as a problem of integration, it shifts the blame and the onus of responsibility for these movements onto migrants themselves.

There is no doubt that the resurgence of far-right populist politics across the world poses a direct threat to the rights and safety of migrants and minorities, to the future of democratic coexistence, and to the future of the nation-state as a multicultural and multiethnic space.Now no less an intellectual authority than Tony Blair has lent his money and his wisdom to this issue, and found the explanation for it.

In a forward to ‘The Glue that Binds: Integration in a Time of Populism’ by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, the Great Man notes that

failures around integration have led to attacks on diversity and are partly responsible for a reaction against migration. On the other hand, the word multiculturalism has been misinterpreted as meaning a justified refusal to integrate, when it should never have meant that…In this report, we make it clear that there is a duty to integrate, to accept the rules, laws and norms of our society that all British people hold in common and share, while at the same time preserving the right to practise diversity, which is fully consistent with such a duty.

Blair goes on to argue that:

…government cannot and should not be neutral on this question. It has to be a passionate advocate and, where necessary, an enforcer of the duty to integrate while protecting the proper space for diversity. Integration is not a choice; it is a necessity.

This is not the first time that Blair has made these arguments. In a 2006 speech as Prime Minister he warned that Britain’s different communities had a ‘duty to integrate’ and that that ‘basic values’ should take priority over ‘separate beliefs and customs’.

Blair also insisted that ‘Our tolerance is part of what makes Britain, Britain. So conform to it; or don’t come here.’ These warnings were clearly aimed at Muslims in Britain, and in case anyone had any doubt, Blair also noted that the July bombings had thrown the question of ‘multiculturalism’ into ‘sharp relief.’

So it isn’t surprising to find him making similar arguments now as an antidote to far-right populism. The report is more nuanced and balanced in its conclusions than its media coverage suggested, but its basic line is that the rise of the far-right is primarily due to ‘ Anxiety in host communities ….driven by the rapid pace of change, fears of segregated communities, competition for scarce resources, fears over values and fears of crime.’

There is a lot to unpick about these claims. Which communities are ‘segregated’ and how did this happen? Is such ‘segregation’ due to a failure on the part of governments or the ‘host communities’, or is it due to migrants who have interpreted ‘multiculturalism’ as a ‘justified refusal to integrate?’

Why do ‘fears of crime’ always equate with ‘anxiety’ about migrants and immigration? What basis do ‘fears over values’ have in reality, and why are they always raised in regard to migration?

The report does not really answer these questions clearly. It doesn’t engage at all with the possibility that these anxieties have been deliberately fueled, for example in coverage like this:

Though its authors include case studies of integration policies by some governments, the report avoids specific analyses of the rise of Trump, Salvini, Golden Dawn, UKIP etc, and makes no attempt to analyse the common threads that connect these movements.

Instead it concentrates almost exclusively on the absence of integration as a common explanation for the rise of the far-right:

One of the principal fears associated with immigration is that it undermines the norms and values that bind society together. These fears are exacerbated when newcomers are perceived as not adapting to the host country’s language, culture and identity—or, worse, when newcomers are perceived as retaining cultural norms and practices seen as fundamentally in conflict with those of the majority. Communities that live apart from the mainstream, whether religiously, ethnically or linguistically segregated, reinforce these fears and make publics wary of growing diversity.

Once again such observations do not ask why migrants are ‘perceived’ in this way, nor do they address the constant slippage between perception and reality. Usually these notions of ‘segregation’ refer to Muslim communities, though the report does not spell this out.

It does not address the extent to which questions of culture, religion, values and identity have replaced ‘race’ in the new ‘identity politics’ of the far-right and its populist variants. It does not consider the possibility that white supremacist, white nationalist and fascist movements have an ideological worldview and political salience of their own that has always used the supposed unwillingness or inability to integrate as a justification for racial Othering.

There was a time, for example, when the supposed unwillingness of Jews to assimilate was constantly used by antisemites as a justification for their exclusion and removal. Similar arguments are now routinely used in the depiction of Muslim ‘no go areas’ and ‘Londonistans.’

The report’s unwillingness to look at the continuities and differences between the new far-right and its predecessors, or between the fringe movements and their more mainstream populist representatives is not entirely surprising.

After all, Blair himself once declared that we should ‘build bridges’ with Steve Bannon and the far-right – a generosity of spirit that he has never extended to the left.

In keeping with his political ecumenism, Blair also a ‘friendly meeting’ last year with the Lega’s Mateo Salvini in Italy, where according to Salvini they discussed ‘immigration, Brexit and energy polices.’

One wonders if this discussion covered the ‘anxieties’ that led Salvini to block boats of refugees and impose a curfew on ‘ethnic shops‘ because their clientele consists of ‘drunk people and drug dealers’ who ‘ piss and shit everywhere.’

Salvini was clearly not trying to assuage ‘anxieties’ about immigration when he said this, anymore than Trump was when he referred to undocumented migrants as ‘animals’ and criminals.

Whether intentionally or not, the unwillingness of Blair’s foundation to consider that racists might actually be racists because they are racist effectively shifts the blame for such movements on migrants themselves or on ‘progressive governments’ that have supposedly failed to take the interrelated issues of integration and national identity seriously.

Few people would disagree with the report’s suggestion that ‘ respect for the law, democratic norms, the ability to speak a common language and the desire to contribute positively to society’ are essential elements for integration.

But the report suggests that migrants are not doing this, and that perhaps they are not willing to belong to a model that favours a ‘ single unified story over parallel lives and asks every group to contribute to a common culture.’

Last but not least, the report ignores the obstacles to integration emanating from within the ‘host communities’ – that have resulted, for example, in EU citizens who have lived in the UK for decades being told to ‘go back where they came from’ and physically and verbally abused for speaking their own languages or even speaking with an accent.

The report is not without useful proposals, though many of them are common sense. As a tool for combating the far-right it is worse than useless. It does what too many governments – including the ones that Blair once headed – have done again and again.

Instead of challenging the ‘anxieties’ that far-right movements feed on, the report’s framing and use of language only confirms these anxieties.

In framing the problem of the far-right as a problem of integration, it shifts the blame and the onus of responsibility for these movements onto migrants themselves. Without actually endorsing forced assimilation it flirts with vague authoritarian notions of coercion that are not far removed from it.

This didn’t work when Blair was in power, and the experience of the last decade makes it clear that it is not going to work now.

Matt Carr is a writer, campaigner and journalist. His latest book is The Savage Frontier: The Pyrenees in History and the Imagination (New Press/Hurst, 2018). He blogs regularly at The Infernal Machine.

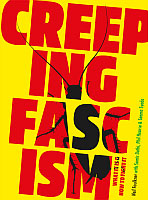

Creeping Fascism: What It Is and How To Fight It

Creeping Fascism: What It Is and How To Fight It

By Neil Faulkner with Samir Dathi, Phil Hearse and Seema Syeda

How can we stop a ‘second wave’ of fascism returning us to the darkest times? How do we prevent the history of the 1930s repeating itself?