Colin Leys writes: The UK government’s handling of the pandemic does not look good. The country is locked down at enormous economic, social, and psychological cost, while the number of people dying from the infection is rising towards a thousand a day.

As a result of the lockdown, which began on 23 March, it is hoped that the numbers being admitted to hospital, and the numbers dying, will soon start to decline, thanks to the interruption of community transmission. Of course, the interruption is only partial, because essential services must continue to be provided, and people need to go out to shop and see their doctor and take exercise and not all keep a safe distance. The government says the hospitals can cope, but so far they cannot prevent some 15% of their COVID-19 patients, especially those with co-morbidities, from dying. One hospital in London that had four wards ready for COVID-19 patients a few weeks ago now has eighteen wards open and full, while huge temporary hospitals are being prepared in several conference centres around the country, with correspondingly large temporary mortuaries.

The problem now is that until an effective vaccine is developed and mass-produced, which could take up to eighteen months, the lockdown will have to continue, which is impracticable on every ground, until some other way of containing the pandemic is found. Anthony Costello, a professor of global health at University College London and former director of maternal and child health at the World Health Organization, argues that there is only one option: to test for the virus on a mass scale, with a nation-wide field force capable of tracing and isolating contacts at the local level, until a vaccine is available. This could enable something like normal life to resume, with ongoing local lockdowns sufficient to prevent a fresh surge in infections – the policy being pursued, notably, by China and South Korea. At this point, however, no such field force is on the government’s agenda.

How the UK arrived at this situation may one day be fully accounted for. Perhaps there will be a public inquiry, like the Chilcot inquiry into the UK’s participation in the attack on Iraq, which lasted seven years and thus reported too late to prevent the disaster being repeated. But it is possible to work out what has happened, or has not happened, and we need to try to keep the record straight. The decisions that the cabinet and prime minister – himself now in intensive care with COVID 19–have had to make are undeniably difficult. Little is yet known about the new virus, and balancing the need to protect people from it against the need to protect people with every other kind of health need, and all the collateral victims of the lockdown, is extraordinarily complex and involves painful choices. But we should nonetheless record the circumstances and what we have been told about them.

A team of Chinese doctors submitted a report to The Lancet, the leading British medical journal, which published it on 24 January. It concluded that the new coronavirus was being transmitted between humans and had a case fatality rate among the hospitalized patients studied of 15%, and urged other countries to prepare for it. At that time Boris Johnson’s government was fresh from winning a large parliamentary majority in the general election of December 2019, on the basis of promising to “get Brexit done” by 31 January 2020.

In these circumstances the Chinese warning clearly did not reach the cabinet, which the prime minister was in any case busy planning to “reshuffle” with a view to delivering on its other main election promise: to “level up” the economies of the deindustrialized North and Midlands, from where the key support for Brexit, and for the Conservatives in the December election, had come. Apart from the flooding, this was the only significant concern of the cabinet throughout February.

The cabinet reshuffle began on 13 February, and involved a telling incident: the Chancellor of the Exchequer (the minister of finance) resigned rather than accept that his special advisers should be replaced by advisers selected by the prime minister’s chief adviser, Dominic Cummings. Cummings was credited with having been the mastermind behind both the 2016 referendum vote to leave the European Union and the Conservatives’ December 2019 election victory, and had been given the extraordinary powers that led to the departure of the finance minister. He was openly contemptuous of the way government had traditionally been conducted. He intended to run it in a new way, using new kinds of unorthodox thinkers as policy advisers, strongly controlled from the prime minister’s office. Civil servants were under notice to conform or quit.

This new policymaking culture was being imposed just when the pandemic was taking hold. Such senior professional advisors as the government’s Chief Medical Officer (CMO) and Chief Scientific Adviser (CSA) represented yesterday’s way of doing business. Their advice on how the pandemic should be tackled was mixed with advice from Cummings and also from David Halpern, the head of the prime minister’s “Behavioural Insights Team”, or “nudge unit”. Halpern was interested in the potential of the pandemic to give rise to “herd immunity” through the infection of a large enough proportion of the population. Cummings also showed an interest in this, and the CSA, Patrick Vallance, even put a figure of 60% on the proportion that would need to be infected.

This gave rise to heated protests from epidemiologists, who pointed out that it was not even known whether the new virus conferred any immunity–or, if it did, for how long it did so. It also attracted criticism from many others who considered it outrageous to rely on herd immunity at the expense of an unknown toll in deaths. It actually seems unlikely that anyone was pushing this as policy. The development of herd immunity was assumed, rightly or wrongly, to be a fact, and its casual introduction in the debate seems rather to indicate a lack of appreciation of the gravity and urgency of the threat on the part of the non-medical advisers. Halpern, for example, speculated as late as 11 March that while herd immunity was being acquired vulnerable people in care homes might need to be “cocooned” for their protection, with the help of a volunteer force of students who could be trained over the coming summer.

The impact of Cummings’ new policymaking culture was all the more serious because of the effects of the Conservatives’ attempt in 2012 to turn the National Health Service (NHS) into a healthcare market. This had included abolishing the Health Protection Agency (HPA), an organization independent of the Department of Health, which had been charged with protecting the population in health emergencies; its functions were merged with those of health promotion, in a new organization called “Public Health England” that was attached to the Department of Health. HPA’s regional personnel were redistributed to some 150 town and county councils and subjected to budget cuts which by 2020 had reduced them to impotent teams of as few as two or three people. So by the time the pandemic struck, protection against an epidemic was no longer the responsibility of any single body with resources and status, or implementation capacity on the ground. The CMO was no longer in direct charge of managing pandemics, but only one adviser among others, with no budget. A symptom of the consequences was that serious shortcomings in pandemic preparedness revealed in a routine exercise in 2016, and reported by the then CMO, were not acted on. Another striking symptom of the dispersal of responsibility is that there is still (in early April) no single official website, such as exists in other countries, providing daily updated comprehensive official information on the progress of the pandemic.

During February the Department of Health and Social Care did, however, produce a Coronavirus Action Plan, and the prime minister called a meeting of the Civil Contingencies Committee to discuss it on 2 March. The plan called for “phased actions to Contain, Delay, and Mitigate any outbreak, using Research to inform policy development”. “Containment” meant following up new cases and isolating them and their contacts, focusing mainly on individuals entering the UK from abroad. “Delay” meant slowing the spread by encouraging people to wash their hands and self-isolate if they had symptoms, so as to slow the onset of peak demand on the NHS. “Mitigation” meant caring for infected patients, and helping other people and organizations affected by the pandemic. The plan document foresaw that the virus would spread and warned of likely deaths, but its general tone still suggested that the impact was not likely to need more than good behaviour on the part of the public.

This impression was reinforced when on 11 March the government introduced a budget which, while providing £3 billion for the mitigation phase of the Action Plan, was otherwise entirely focused on delivering Brexit and “levelling up”. At the same time, the NHS started restricting testing to patients admitted to hospital. This was presented as a shift from containment to mitigation, but it was dictated by the fact that the NHS’s whole testing capacity–then just 1500 tests a day–was barely adequate to deal even with the sharply rising number of suspected COVID-19 patients being admitted to hospital.

Behind the scenes, however, both Public Health England and a team of modellers based at Imperial College London were finally getting their message through to the politicians in reports which became public on 14 and 15 March. They concluded that the existing policy was likely to lead to 7.9 million hospital admissions, which would overwhelm the NHS, and cost some 250 000 lives. In a series of reluctant steps over the next week, the cabinet eventually accepted the need for an enforced national lockdown. Their reluctance was due partly to awareness that the public would hate it and fear that the government would pay a political price, partly to the fact that the cost would bury their political project for “levelling up”, as indeed it did. The £3 billion allocated to mitigation in the 11 March budget disappeared into the £350 billion committed to supporting the lockdown less than three weeks later. They also had to swallow their intense dislike of state intervention of any kind. Worst of all, there was no exit strategy.

There were plenty of criticisms of the lockdown, most of them based on the fact that the modelling it was based on depended on assumptions for which there was little solid evidence. It was bound to reflect the experience of previous epidemics, but the new coronavirus was unlike previous ones in crucial ways: for example, its lethality might prove much less than was being assumed. But the most telling criticisms came, as described earlier, from Anthony Costello, and the editor of the Lancet, Richard Horton. They endorsed the precautionary principle that underlay government policy but attacked the government for failing to act much faster, and above all for failing to undertake mass testing while tracing and isolating the contacts of every positive case. Epidemics, they pointed out, have regional and local areas of intensity, arguing that it is only by identifying these and clamping them down that national epidemics can be suppressed – not eliminated, but managed – so that national life can recover.

This criticism showed how the lockdown could be ended, but it also highlighted the fact that even if the government had been focused on the pandemic in February, the capacity to implement the nation-wide community-based testing, tracing, and enforcement of local quarantines that are needed did not exist. An adequate pandemic preparedness plan in a rich country should have included this, but the UK’s did not. On the contrary, the deliberate financial starvation of the NHS over the previous decade had left it short of capital equipment; bed numbers, including intensive care beds, had been cut to the bone, and there was still a shortage of some 5,000 doctors and 40,000 nurses. As the disease spread during the lockdown the lack of preparedness came into public view in a new way: there was not enough testing capacity even to test NHS staff to ensure that they were safe to work with patients, or enough personal protection equipment to keep them, or the staff of residential care homes, from becoming infected. Ventilators were also in short supply. It emerged, too, that the government had spurned an opportunity to join an EU initiative that had begun in January for the collective procurement of equipment to fight the pandemic. The government later claimed, falsely, not to have known about it.

Unfortunately, spin has become the default response of UK governments to any criticism, and the fact that the NHS’s lack of readiness and capacity was the result of successive Conservative government policies pushed the official spinners into overdrive. Besides routinely understating the risk, officials and ministers serially misled the public and substituted nationalistic and militaristic rhetoric for honest acknowledgement of the problems they and the country faced.

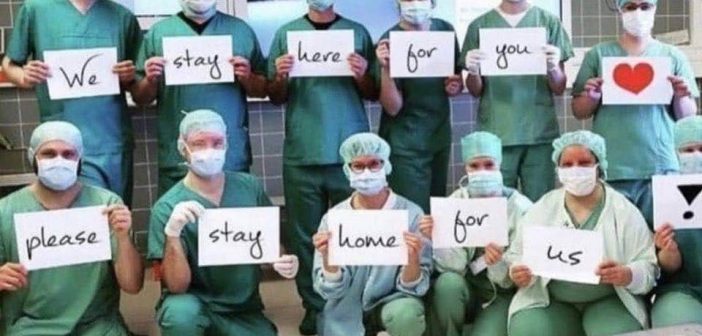

Meantime, and in contrast, NHS hospital staff at all levels have responded with impressive speed to the terrifying surge of seriously ill patients, rapidly repurposing both hospitals and clinical specialists and caring devotedly for COVID-19 patients at high risk of becoming infected themselves – a risk hugely increased by the shocking shortage of adequate protective equipment. In the hospitals no one goes uncared for, even as the dead become too numerous for the mortuaries to contain (the plight of the 400,000 highly vulnerable people in predominantly private care homes is another story, and a shocking one). The surge will fall back, and sooner or later a rational programme to manage the pandemic will be adopted, the lockdown will be limited, and eventually a reliable vaccine will, presumably, be available. But new viruses will appear, and the question remains whether the UK will learn a sharp enough lesson from this one to restore the NHS to financial health and adequate preparedness for the future.

Colin Leys is an emeritus professor of political studies at Queen’s University, Canada, and an honorary research professor at Goldsmiths, University of London. A political economist of development and healthcare whose work has spanned a wide range of topics, from decolonization in Kenya and Namibia to socialism in contemporary Britain, Leys has written powerfully and extensively against the privatization of the UK National Health Service (see, e.g., here, here, and here).

This article was first published here