Source: The Guardian

Rosa Luxemburg’s letters bring to life a humane socialist whose ideas still resonate today

Edwardian England, with its rituals of roast beef and empire, was grimly inimical to social change, yet Lenin sought refuge there in the early 1900s while on the run from the tsarist police. In London he took his protege Trotsky round the Jewish heartlands off Brick Lane. The Whitechapel backstreets had long served as an asylum for international socialists and dreamers of every stripe.

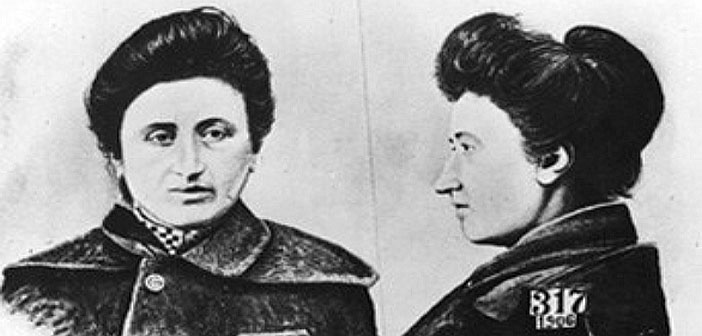

Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-born internationalist, found the Whitechapel district “dark and dirty” on her arrival in 1907. The 36-year-old had come to London from Berlin to attend a congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour party (soon to become the Soviet Communist party). Among the delegates were Lenin, Trotsky and a walrus-moustached future apparatchik called Stalin.

Revolution was in the air. Stalin, then little known outside his native Georgia, had settled in a Whitechapel Road boarding house. His landlord, a poor Jew, spoke Russian. The area, with its obscure exuberance of life, fascinated Luxemburg. It was a sanctuary for Ashkenazi Jews who had escaped the pogroms in 1880s Russia. Their side-locks, kaftans and Yiddish would have struck Luxemburg as backward tribal marks.

Like Trotsky, Luxemburg was an example of Europe’s new, secularised Jew. Her father, a Warsaw timber trader, considered himself assimilated within the Catholic majority. Luxemburg herself regarded her Jewishness as an irrelevance. She cared little for the derision and sorrows heaped on her co-religionists in Russian territories. “What do you want with this theme of the ‘special suffering of the Jews’?” she upbraided her friend Mathilde Wurm in 1917. “I am just as much concerned by the poor blacks of Africa.”

Yet, to judge by this absorbing new collection of her letters, she was inevitably shaped by Judaism and its fierce moral parables of deliverance and survival. The self-ironical humour and love of learning of her “forefathers” were characteristics that Luxemburg saw in herself. Written in German, Polish, French and Russian in the years 1891-1919, the letters radiate erudition (as well as an occasionally acid tongue). During her imprisonment in Berlin for anti-militarist beliefs she read Goethe and Cervantes, and marvelled at the “bantering hobgoblin mood of A Midsummer Night’s Dream“. The letters are also fraught with punctilious descriptions of nature, from honey bees to the “dwarf-sized yarrow plants” blooming in the prison yard.

Like many secular Jews, Luxemburg applauded the 1917 uprising against the Romanov monarchy. “The events in Russia are of amazing grandeur and tragedy,” she wrote to a social democrat friend from her cell. At the same time she was appalled by the prospect of Bolshevik mob rule and condemned the violence unleashed by Lenin and Trotsky against counter-revolutionaries. The Bolshevik use of terror was, in Luxemburg’s pacifist view, an expression of political “weakness” and the trapdoor disappearance of innocents disconcerted her greatly.

In January 1919, against her better judgment, she lent her support to the communist uprising in Berlin. Hoping to repeat the success of the October revolution, the left-wing Spartacist League (of which Luxemburg was a founder) was brutally crushed by proto-Hitlerite Freikorps. Luxemburg was clubbed to death by nationalists and her body dumped in the Landwehr Canal, between what would later be west and east Berlin. She was 47. “The old slut is swimming now,” somebody remarked. No one stood trial for the murder of “Red Rosa”.

In the 30s, her name was blackened further by Stalin, who scorned the apparently bourgeois cult of “Luxemburgism”. Her reputation was allowed to revive only after 1956, when Khrushchev publicly denounced Stalin. Her most famous slogan – “Freedom is also the freedom of those who think differently” – was adopted by student protestors in East Germany in 1988, a year before the Berlin Wall came down. That same year, Margarethe von Trotta’s soberly elegiac film, Rosa Luxemburg, was released.

If anything, Luxemburg’s insistence on social justice seems more pertinent now with the world financial crisis. Her main theoretical work, The Accumulation of Capital, sought to counter the lure of the market. A deep-dyed democrat, Luxemburg hated what she called the “German mentality” and reputation for officiousness, and saw her role as somehow Russifying Germany. Punctilious in answering her letters, she fired off hundreds of missives to friends, lovers and colleagues, some of them very lengthy. Her need to write was clearly overwhelming and she wrote as though she was thinking aloud, the words pouring out. “God forgive me this prose poem of wretched quality!” she apologises to a journalist friend in 1898.

In her personal life, Luxemburg displayed a middle-class fastidiousness at odds with her combative politics. The sight of women on bicycles she found “aesthetically displeasing” and she flinched from displays of too much leg. A soapbox “fighter” rather than a soulless statistician, she championed the cause of Polish and German coal miners, shoemakers, tailors, party workers. Socialism for her was above all a comradely ideology that sought to address inequalities. Notably, these letters reflect personal anxieties of betrayal (“The jibber-jabber of our wavering friends”) and political danger. Speaking to audiences of up to 5,000 people, she was vulnerable to the assassin’s bullet.

Published to coincide with the 140th anniversary of Luxemburg’s birth in March 1871, The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg come as near as anything to the way this extraordinary woman talked with loved ones and friends. Perhaps for the first time in English, Rosa Luxemburg emerges whole from the shadows of Stalinism and previous biographers. This is a wonderfully compelling record, both poignant and timely.

The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg

The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg

Edited by Georg Adler, Peter Hudis, and Annelies Laschitza

Translated by George Shriver