Charisma is an overused word, but he had it by the bucket load, he was the man you most wanted to bump into walking round a corner.

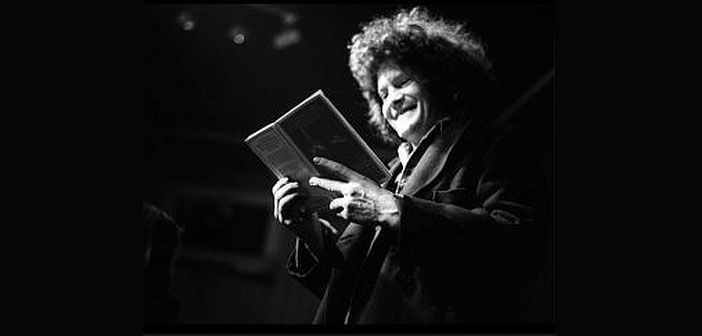

Source: Albion Beatnik Bookstore

Heathcote Williams died recently, undoubtedly to be missed greatly by all who met and spoke with him. His life’s narrative of creative achievement, if a medical graph, flipped from artistic ruddy health to a hypochondriacal sick bed, but always back to health again; his basic pulse was brilliance.Heathcote Williams’ finest hour was as a Royal Court playwright. He had been discovered, encouraged and then feted first by Harold Pinter, who he had met in a barber’s shop. The play AC/DC was his theatrical high tide, it met near ecstatic critical review when staged first in 1970; it transferred to New York the next year.

Evident even then was his profound anarchism: the play presaged the chaos and intellectual free fall of the digital age (it closes with an amateur trepanning as riposte to the “information explosion” in which “all ideas and opinions would be available to all people and therefore rendered impotent”); it lambasted the hollowness of fame and the pall of the media (it is thespian McLuhan with make-up), also the vox pop self-obsession of the work of his friend, the psychiatrist R.D. Laing (they remained friends even after Heathcote was reputed to have had an affair with Laing’s wife). It grew out of a one act play he had written at Pinter’s behest, The Local Stigmatic (Al Pacino became obsessed with it and, funded with Jon Voight, filmed it himself). It was described at the time as the “first play of the twenty-first century” by the Times Literary Supplement, and its bold experimentation greatly influenced Ken Campbell and Mike Bradwell’s later work (Campbell had already directed an earlier play by Williams at the Royal Court); its utter contempt for the media was way ahead of its time, and possibly that came to fruition only thirty years later with the death of Diana Spencer, Chris Morris and Ali G in its tragic wake.

Heathcote himself was a Hollywood parvenu character actor, most credibly as an excellent Prospero in Derek Jarman’s The Tempest (“occasionally intelligible,” wrote The Times) [1979], most lucratively in Basic Instinct 2 [2006]. He was a guest in the star-studded final episode of the fourth series of Friends. His CD recordings of Dante, the Bible and his own work sparkle.

He was a pioneering squatter. He founded Albion Free State in a derelict bingo hall in early 1970s Portobello; the Notting Hill office for Free Head Press, set up in 1974 to publish and distribute “anarchist porn,” became the Embassy of the Republic of Frestonia in 1977, an emblematic thorn in the side of the landlords of London for nearly a decade; he helped establish the Ruff Tuff Cream Puff estate agency to match squatters to abandoned buildings. He was a prolific graffiti artist, and his calligraphic Tourettes erupted like acne on the walls of Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove in the late 1960s and early 1970s, even once on the walls of Buckingham Palace. His one-liners became humourous haiku-style legend.

He was, too, a proud conjurer, a member of the Magic Circle; despite a botched attempt at levitation in the National Theatre a few decades ago and a disastrous fire-eating episode on the doorstep of Jean Shrimpton in the 1960s, his magician’s self-belief incredibly never wavered. His short TV play What the Dickens!, about Dickens and magic, was shown by the BBC over Christmas, 1983.

Periodically he was also an occasional artist and sculptor: he spent reclusive years in Cornwall for apprenticeship. He loved nature, reflected in his poetry, and he very proudly discovered a breed of honey-making wasp on one naturalist trip to South America.

Heathcote had a reassuring and magnetic personality. Charisma is an overused word, but he had it by the bucket load. With such a gift he became a useful catalyst to meld the otherwise diverse shards of London’s counterculture of the 1960s (when he lived as tenant of fellow poet Michael Horovitz) and the 1970s (a decade of attitude and squatting), whose underground newspapers were rent asunder so often by maverick ego.

His febrile imagination, quick repartee and grandstanding gifts imagined and crafted ideal front page stories. His work in the 1970s for International Times helped maintain its momentum, his commitment to its resurrection more recently was more than nostalgic.

He wrote also for the vegetarian newspaper Seed, the animal rights newspaper The Beast, and other more peripatetic and European based journals. In 1969 he co-founded Suck, a mouthpiece for the sexual revolution that followed the swinging sixties; Germaine Greer was a partner in this venture. The magazine’s self-conscious childishness and felt tip design mentality was a forerunner for the latter-day zine; its content ranged from the tame to the disturbing (as were his lyrics for a 1979 Marianne Faithfull record, Why D’ya Do It, when, it is said, EMI’s female warehouse workforce threatened extraordinarily to strike). Suck was published in Amsterdam, and Heathcote continued to be published in Holland for Rotterdam’s stylish Cold Turkey Press.

Throughout his life Heathcote Williams was notoriously reclusive. He retreated after each dabble with fame – as a playwright in the 1970s, as a bestselling poet in the late 1980s. He declared fame to be the “first disgrace.” Rarely would he be interviewed, though he was open and discursive whenever he was. A 1993 BBC mock documentary, Every Time I Cross the Tamar I Get Into Trouble was made exploiting this evasiveness; he made an incognito guest appearance at its end.

His polemical, lengthy poem Whale Nation met great acclaim (to his horror) and was published in 1988, when it paid booksellers’ rents for several months: he gave its substantial royalties away (his American advance alone was said to be six figures). His recount of a reading at the Glastonbury Festival was hilarious. That book was followed by Sacred Elephant [1989] and Autogeddon [1992], both similarly erudite and didactic, occasionally prolix. A publishing hiatus was stalled in the last decade of his life by a flurry of collections; a recent pamphlet demolished Boris Johnson in the Swiftean tradition of broadside, became a cause célèbre and a bestseller before the referendum: Brexit Boris: From Mayor to Nightmare.

As a poet he stood in the tradition of William Blake, his tenor and his rhetoric. Form and rhyme were arbitrary, the crooked road more interesting. Like many Anglo-bijou beatnik poets of his generation, his true heroes were Blake and Shelley, and he was well versed in both the English poetic and political tradition.

That Heathcote was a very great poet, I have no doubt. But for what he stood for rather than for what he wrote or how he wrote it; to me his poetry suggested boulders falling from cliff tops, sometimes they smashed beauty in their descent. He was anarchic (in his routine life as well, snatches of repast and rest where taken as required, his work station a playpen with no fixed abode), anachronistic, playful and prone to an idée fixe (he sort of didn’t care for Bob Dylan, for example, and he ran with that idea quite a bit), humourous, ribaldic, tolerant, forgiving and kind. He stood for invention and wit, the democratic and demotic, above all he was a random and fearless free spirit, a poetic blunderbuss in an age troubled by dissent and doubting of free speech.

He was always well mannered: his social dish of choice was high tea, his humble variant of High Table (he had been schooled at Eton and studied law at Christ Church, although he never matriculated, he chose to write his first book, The Speakers, instead). The resolve and purpose of its crockery, cutlery and cruet, although clattering and noisy when passed around the table, is gentility and deportment; its ritual is hierarchical, there is nothing more deferential than a place mat, the table cloth is the stuff of order. He was always a blunt instrument in print – words, garrulous and scabrous lava so often, came easy to Heathcote, he could toss off a lengthy poem in no time at all, repression or tongue-tied would have been inappropriate adjectives to use – but in person he was frustratingly modest, to a fault. He was considered, would always give way, so often silent, a mild minx rather than a hussy.

The anarchy of his writing and his life’s mannered decorum rattled likes peas in his emotional pod, but were, for him I think, vital and almost rational schizophrenia (AC/DC was titled originally Skizotopia). This skizotopic aspect gave him ballast, and he rejoiced in its lack of resolution. If you disputed this conflict within him he would only grin, for wit and grace were his bedfellows. In life he was gentle, rarely acerbic, his eyes agog with observation. Theatre director Nicholas Wright said that Heathcote was “the man you most want to bump into walking round a corner.” Indeed he was.

But for all of that, his polemic voice came as a birthright: the polemic, like satire, is the last refuge of the privileged. “Poetry is heightened language,” he said a few years ago, “and language exists to effect change, not to be a tranquilizer.” I’m not so sure about the consistency of that: Marx, for one, made a bad poet. And if the privileged do either polemic or satire (the middle class do sitcom), it is only the working class who do revolution. Heathcote never did revolution, he did reportage, be it writing for the Royal Court theatre, countercultural magazines or poetry presses. He wrote once of Shelley as an outsider, as a traitor to his class, too. But that’s not the stuff of revolution. Perhaps that observation of Shelley was autobiographical displacement.