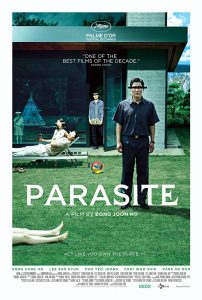

A review of Parasite, (South Korea, written and directed by Bong Joon-ho) by Dave Kellaway

“Ki-taek: They are rich but still nice

Chung-sook, Ki-taek’s wife: They are nice because they are rich

Chung-sook, Ki-taek’s wife: If I had all this I would be kinder”

This is a film for our dark times. Director, Bong Joon-ho, looks behind the shiny Samsung phones and Hyundai cars of the South Korean economic miracle and unmasks the reality of capitalist class relations. He shows how they affect people’s choices and actions. On different levels it is a black comedy, a ghost story and even a bit of a horror film. It manages to engage the audience with a plot that rips along with a great mid-way twist and with characters that seem real and human. At the same time, as the young son says several times in the movie, it’s all about the metaphors. What interests Bong Joon-ho is the huge inequality in Korean society. He creates a lively, enjoyable cuckoo in the nest story but infuses it with some explosive messages.

The story is straightforward. A poor working class family living in a basement in urban South Korea gradually insinuates itself into the life and, more importantly, the domestic economy of a rich upper class one. A friend of the son suggests he takes over the English tutoring role of the rich daughter. Once hired, he manages to get his sister to take over the ‘art therapy’ of the daughter’s young brother. They use a certain creativity and intelligence to achieve this but add a dose of ruthlessness in getting the rich family’s driver and live-in maid sacked and replaced by their own father and mother. The family had to deny its very existence to carry out these roles, an inspired symbolic example of how our very identity is alienated by this system.

The story is straightforward. A poor working class family living in a basement in urban South Korea gradually insinuates itself into the life and, more importantly, the domestic economy of a rich upper class one. A friend of the son suggests he takes over the English tutoring role of the rich daughter. Once hired, he manages to get his sister to take over the ‘art therapy’ of the daughter’s young brother. They use a certain creativity and intelligence to achieve this but add a dose of ruthlessness in getting the rich family’s driver and live-in maid sacked and replaced by their own father and mother. The family had to deny its very existence to carry out these roles, an inspired symbolic example of how our very identity is alienated by this system.

Throughout you get a very physical, visual expression of the gulf between working class and upper middle class living standards. The contrast between the squalor of the basement with people pissing on their windows and the superb architect designed house in the upper quarters could not be clearer. This upper/lower spatial division has been repeated in many dystopian stories with the proles living underground. Most urban centres throughout the world have this very clear physical division between the classes.

A recurrent reference in the film is made to how the rich identify the poor with an unpleasant smell. The businessman in the back of the car talks about the smell of people in the subway and the driver begins to try and smell himself. George Orwell made some similar comments when he wrote ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’.

“It may not greatly matter if the average middle-class person is brought up to believe that the working classes are ignorant, lazy, drunken, boorish, and dishonest; it is when he is brought

up to believe that they are dirty that the harm is done. And in my childhood we were brought up to believe that they were dirty” (Chapter 8)

The smartness, adaptability and abilities of the poor family contrast with the naiveté and vacuity of the rich family further reinforcing the idea that the system does not reward intelligence. But the director does not romanticise working people. The story shows a vicious fight for survival between working people, scrabbling to monopolise the benefits of working for the rich household. There is a great riff in the film on the idea of having a plan. The poor family keeps coming back to that discussion when they find themselves in a crisis. For a while their plans work effectively then their guard falls and they are unmasked. The father comes out with a great line that sums up to some degree the state of things today for working people in many countries. He says – in response to his son asking what the plan is –

‘You know what kind of plan never fails? No plan. No plan at all. You know why? Because life cannot be planned. Look around you. Did you think these people made a plan to sleep in the sports hall with you? But here we are now, sleeping together on the floor. So, there’s no need for a plan. You can’t go wrong with no plans. We don’t need to make a plan for anything. It doesn’t matter what will happen next. Even if the country gets destroyed or sold out, nobody cares. Got it?’

The protagonist role, the collective solidarity and organisation of working people is everywhere in crisis today.

The father’s frustrations at the impasse ends in a bloody denouement in the midst of an expensively organised birthday party for the young son while classical opera is being sung and canapes consumed.

The film reminded me of some of the progressive Italian black comedies of the 1970s by Scola, Monicelli and others such as Brutti, Sporchi et Cattivi (Down and Dirty) with Nino Manfredi or Scopone Scientifico (The Scientific Cardplayer) with Bette Davies directed by Comencini. Films that worked as popular comedies but which had a serious, anti-capitalist point to make. Some of the best Ealing comedies of the 1950s also had this quality, such as the Man in the White Suit (with Alec Guinness). Korean cinema has been making some great films – Burning (2018) was tremendous.

What is striking is the way cinema more easily than some other art forms – through subtitles – can make different cultural realities accessible. Some people have commented that in any case the direction is so adept that the film can be followed visually most of the time without needing the dialogue. The best films always have that visual quality that keeps scenes in your mind long after you have seen it. A good example here is the slapstick antics of the poor family having to escape the house when the rich family come back unexpectedly.

Deservedly winning the top prize at Cannes, this film merits recognition at the Oscars which would be poetic justice in Trump’s America today. Bong Joon-ho brilliantly makes us think about whom the worst parasites are, the rich family or the poor one.