“My health depends on your health. Your health depends on my health. We cannot escape one another. The liberties that we prize so highly depend on the health of all of us.” Richard Horton, Editor of The Lancet

While French health workers have won a pay rise here, in the UK, they are to be charged for parking their cars at work. This in a situation where the UK has 2.7 hospital beds per 1000 population compared to France’s 6.2 and an EU average of 5.2.

I am angry and I don’t think I am alone. Certainly those who have been, or are, NHS patients, will understand me.

For the last six years I have depended on the NHS for my continued existence – for being alive. Not just alive, but able to live an active life in mind and body. This is what happened to me.

In August 2014 I was on the Croatian island of Mljet where every morning my wife Anne and I drank coffee overlooking the Adriatic from the terrace above the harbourside cafe in the small village of Kozarica. Our favourite table was shaded by a pine tree. One morning I stood up and hit my head on an overhanging branch. I was probably on Planet Zembar where Anne says I go when I’m not paying attention to my surroundings. I was left with a mildly throbbing pain.

Two months later and back in London we arranged to meet a friend at The Victoria and Albert Museum. A wet, cold, November Saturday afternoon, an ideal day for a museum visit. Titled ‘Disobedient Objects’ the exhibition we visited was examining ‘the powerful role of objects in movements for social change’.

Hanging from the ceiling was a battered pan lid used by one of the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, on their demonstrations when campaigning for their ‘disappeared’ children during the military dictatorship in the 1970s. There was a slingshot made from the tongue of a shoe that a Palestinian had used against Israeli tanks. There were homemade shields made to look like book covers that had been carried by students in Rome demonstrating against austerity cuts – Boccaccio’s The Decameron, Dante’s the Divine Comedy and George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia. Protected with literature.

It was surreal and my head started to spin. I couldn’t read the text that accompanied the photos and displayed objects. I had to sit down.

We went to the cafe, ordered tea and scones and I tried to pour my tea over the jam. While this was going on, our friend received a call from his wife, and when he told her what was happening she told him to tell Anne to get me to hospital. Anne said that I had been behaving strangely for some weeks. That morning she had found me taking a pee without lifting the toilet lid and that, on our way to the V & A, I had tried to use my mobile phone in place of my travel card.

By the time Anne and I reached Archway station I was incapable of doing little more than lean on her and stagger up the hill to the Whittington hospital.

It was early on a Saturday evening and already busy. I was placed on a trolley in the corridor, but after half an hour was wheeled off and given a CT scan. The diagnosis was not a condition I’d heard of nor wanted to, left chronic subdural haematoma. My brain had been pushed to the right side of my cranium.

I was told that they were finding it hard to get me a bed in a neurological hospital, The London and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen’s Square were the options. Two days later I was moved to Queen’s Square.

There are two types of haematoma: acute and chronic. Acute is the more serious of the two and is caused by trauma when rapid bleeding fills the area between the outer layer of the brain – the meninges – and the brain itself. This can occur as a result of a major blow to the head, in a car accident for example or when skiing. Michael Schumacher was one such victim when he fell, not in a car crash, but while skiing, his injury caused by the camera mounted on his helmet. .

Chronic haematoma also involves bleeding, but this may takes several days or weeks after injury to become apparent. As we get older, our brains shrink which makes us more susceptible to haematomas because the veins are stretched. It can occur after a minor head injury, especially among the elderly. The bleeding presses on the brain. There is competition between blood and brain and when blood wins, the brain is moved off-centre. In severe cases, the lower part of the brain can be pushed where the spinal cord is attached. This is very dangerous because the brain stem is where the impulse to breathe is located.

With all haematomas, small veins between the surface of the brain and its outer covering can, on impact, stretch, tear and bleed. This covering, the dura, is a lining of tissue immediately below the skull that encloses the brain. It is tough and has been compared to a piece of kevlar.

On arrival at Queen’s I was asked if I had recently hit my head. Our attic bedroom has a sloping ceiling, and, in Zembar mode, I often hit my head at night in the dark while making my way to the toilet. But I felt that the Croatian pine tree was the likely suspect, even though it had been two months since our return home from Mljet. Douglas Katz, Professor of Neurology at Boston School of Medicine, has said, “the person may appear fine initially because the mass of blood in the head is expanding and there isn’t too much pressure on the brain yet.” He refers to this as ‘Talk and Die’ syndrome.

And those two months may have been the reason why they found two blood lakes in my head, perhaps the first added to by my Zembar behaviour in our attic bedroom.

When Anne signed the consent form before my operation, they told her the procedure carried risks: seizures, infection, being left in a vegetative state, even death.

Later, she told me that, while I was in the operating theatre, she went to the hospital chapel and lit four candles: one from her and three from my two sons and grandson. She then returned to the ward, staring at the empty space where my bed had been. She says she hoped for the best, but was preparing herself for the worst.

The operation involved two burr-hole evacuations to drain the accumulated blood in my head. It is one of the oldest surgical procedures, known as trepanning, Evidence of trepanation has been found from Neolithic times and was used by the Mayans, Aztecs and Incas as part of their ancient rituals. Shamans used it to purge bad spirits in cases of mental disease, epilepsy and blindness. It was carried out with a piece of flint and without anaesthetic. In some ancient cultures, heads were very significant, and the bone taken out was prized as an amulet.

After the operation, I woke up from the anaesthetic to find that my amulet was a square, flat plastic bag. It was attached by tubing to one of the holes drilled into my head to drain post-op saline solution and any remaining blood.

I was left with persistent expressive asphasia, a partial loss of language, which in my case was accompanied by confusion. Unable to remember my name or date of birth, I dreaded the nurses who regularly took my blood pressure. Their first question was always, ‘Where are you?’ One of them later told me that I would reply out of concern for them with, “Don’t you know?”

I couldn’t sleep and lay awake trying to work out what was going on. A cup of tea would be nice, except achieving it was difficult. I would walk towards the night desk, practising the words I needed. ‘Please, can I have a cup of tea?’ By the time I got there I had forgotten the words. As I stood in silence, the duty nurse would smile, ‘Go back to bed, and I’ll bring you your tea.’

I was now so confused I had no idea how to clean my teeth or wash my hands. I could only say ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to questions. Words on a page no longer made sense. I had lost the ability to speak in sentences or to read. A speech therapist came to my bedside with word exercises. At first, I was unable to read single-syllable words like ‘book’ and ‘cold’. ‘Read book’ and ‘Cold Day’ were beyond impossible.

I was given a sheet with pictures and words underneath and asked to point at an image and then its word definition. On the first row in the first box was a bear holding his head. The text underneath said, ‘I’m in pain.’ I struggled to decipher ‘pain’. Stumbling over the tangle of letters, I finally managed to pronounce the word. When the therapist asked me to read the next box with four bears holding hands that said ‘I want my family’. I answered with ‘sad bears’.

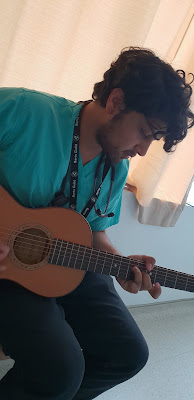

My Brazilian friend, Deicola Neves, brought his guitar and played bossa nova to the ward. He tried to get me to play, but I couldn’t remember a single chord.

I don’t recall being frightened from the moment I arrived at the Whittington to the moment I left Queen Square. I wasn’t even fearful when they took me to the operating theatre.

At time of death, it is said that the body releases chemicals that ease the mind from feelings of panic and fear. Perhaps this also happens when your skull is about to be opened. My consultant told me that patients facing trepanning manage to hold themselves together to be able to get through it. She added that patients who worry the least take longer to recover because the mind, which fights off fear at the most critical of moments, only delays the trauma, but cannot avoid it.

Four days after the operation, and with no improvement, my consultant stood at the foot of my bed. She was unhappy with my progress because of my inability to speak and read. I was told I might have to have a second, more invasive, operation.

Anne asked what was involved. The consultant explained that a new window of bone would have to be cut out of my skull so the brain could be scraped. This procedure would remove the old, dried blood from previous bleeds in the hope that my ability to read and speak would be restored. There was, she said, no guarantee of success and that there were risks.

As soon as she left my bedside, I indicated to Anne to hand me the sheet the speech therapist had given me that morning. I had been able to read the one word, pain. I slowly read out all the captions under all the pictures.

I have no explanation for this, except that hearing about a possible, more dangerous operation unlocked the fear in my mind. I began to speak and read. Within two hours, I was talking reasonably.

The nurses and cleaners came from Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Uganda, India, the Philippines, Poland, Lithuania, Ireland, England, Columbia, Spain, Portugal. The surgeons were from Italy, China, Ireland, the Philippines and north London. The surgeon who saved my life was Nigerian.

Friends sent me flowers, fruit and cards. Lapsed Catholics lit candles, an Iraqi atheist friend who was in Tunisia made a Friday visit to the mosque to pray for me.

When I was well enough to leave the ward, Anne took me to the chapel where she’d spent an hour each day between the morning and afternoon visiting hours. On entering, I saw a notice saying that THIS CHAPEL IS FOR ALL FAITHS.

On a table near a bank of candles there was a visitors’ book. In that book one inscription read, ‘Thanks to all gods and goddesses and the NHS.’ Another was, ‘Mum was always heading for heaven. But please God, not yet.’

I wrote my own message. In place of the gratitudes to deities, mine said, ‘No offence to Jesus, but he didn’t save me. The NHS did.’

* * *

Three years later, I needed the NHS again. Just before Christmas in 2017, I started getting short of breath when walking uphill or going upstairs. I was also peeing a lot and was concerned about my prostate. I went to my GP and told her my symptoms. She listened to my heart, dropped her stethoscope and told me I must go immediately for an echocardiogram. It’s an ultrasound scan and a small probe is used to send out high frequency waves that create echoes when they bounce off the heart and nearby blood vessels.

It was carried out at a private clinic, the InHealth centre in Ealing, West London. This is one of the growing sub-contracted NHS services and each test costs the NHS £350.

I was diagnosed with atrial fibrilation and aortic stenosis, a heart rhythm disorder along with a narrowing of the aortic valve opening, which causes restricted blood flow.

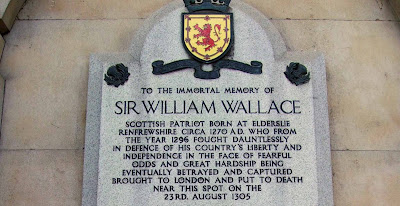

In early February 2018 I was admitted to St Bartholomew’s Hospital. This area of Smithfield has been the scene of both healing and butchery for over a thousand years. There has been a hospital on the site of the St Bartholomew Priory since 1123, and the meat market is within sniffing distance. It has also been a place of execution. On a wall enclosing the hospital is a plaque that says the Scottish rebel leader William Wallace, ‘Braveheart’, was hung drawn and quartered here in 1315. Sixty years later, the leader of the Peasant’s Revolt, Wat Tyler, was decapitated on this site by the Lord Mayor of London, who then stuck his head on a spike.

In the 19th century, with the growing interest in anatomy and the education of surgeons about the human body and anatomy, Barts had its own body snatchers, or resurrectionists, who were paid to bring in the corpses of the condemned for dissection.

I was there thankfully, neither for decapitation, nor as a medical specimen, but to have an aortic valve replacement. This open-heart procedure involved removing the damaged valve and replacing it with one that can be metal or made from either synthetic or animal tissue. In my case it was to be bovine—from a cow.

Before surgery my body was cooled down from its normal temperature of 37C to18C. The cold slows the body’s metabolism, lessening the risk of brain damage. I was placed in suspended animation with no pulse, no blood pressure and no brain activity. A sort of induced hypothermia. This allows the surgeon to stop the heart long enough to carry out the procedure.

A heart-lung bypass machine replaces the heart function for the duration of the surgical procedure. Once the operation has been completed, the patient is warmed up, and the heart restarted. Yale’s New Haven Hospital’s heart surgeon, Dr John Elefteriades says of this process, “It is the most fascinating technique to which I have ever been exposed in medicine and each time, it seems a miracle to me that it works.”

Anne was there post surgery when I was being warmed up in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), tended to by my own specially-trained nurse. I was wired and tubed up and when the nurse turned the propofol off, Anne was shocked because I went from a comatose state to one of agitation. When I awoke, she said, I shot up like Frankenstein’s monster.

I remember very little about the cab journey home, but Anne told me I was crying, and pointing excitedly at passers-by, glad to be alive.

Our cat seemed to understand my convalescent condition and spent the following days while I recuperated by jumping onto the end of the bed and not my chest as he had done before. Then he would settle himself across my legs and purr. He only left me at meal times and to use his litter tray.

But even with cat therapy, my health problems were not over because six months later, when reading on the couch, I started screaming that I had lost feeling in my left hand and leg. Anne remembered the acronym, F.A.S.T., to determine if someone had had a stroke. She first checked my Face. It was not drooping, but I could not feel the left side of my face. When she asked me to raise my Arms, I could raise them both, but struggled to get my left arm to eye level. I could Speak, but I was slurring my words. She decided that it was Time to call 999.

The paramedics arrived in minutes. They confirmed it was a suspected stroke and, because I was unable to walk, they bounced me down the stairs in their evacuation chair. Twenty minutes later, we arrived at University College Hospital. That is the advantage of living close to the centre of London and being beneficiaries of the capital’s NHS ambulance service. My stroke was bad, but it could have been a lot worse.

From UCH I was moved to Barts where they decided my new heart valve had been infected by a bacteria called streptococcus equinuus. They suspected that the bacteria that caused my endocarditis could have entered my body through the gums or originated in the colon.

Every morning the ward consultant would cheerily tell me that they might have to operate again to replace my infected valve. I was placed on an intravenous drip while they tried to work out what drug could get rid of the infection.

Fortunately, Barts clinical laboratory found a drug that successfully attacked the bacteria. Only after I left Barts did I learn that it was touch and go whether they expected me to live.

I was at Barts for seven weeks. The drip was resupplied every four hours. My temperarure was checked at the same time as was my blood pressure. Massively impressive and caring treatment.

Spending nearly two months in hospital means you get to know your fellow patients.

Barry, a Jamaican, had already had three heart operations when he arrived at Barts for his fourth. His operation lasted 28 hours and they ‘lost’ him three times. He told me about his out-of-body experiences which had left him scared to go to sleep. He badly needed psychological care, but with the level of cuts in NHS funding, this was unavailable.

Just as food is important to getting better, so is after care.There was a time when post-operative patients would spend time in convalescent hospitals. No longer. In Germany, and even in the former Yugoslavia where I used to live, all operations included a minimum of one month’s post-op stay at a health spa.

What memories do I take from the time I spent at Barts? Not the operation and its after-effects of pain and worry, but the nursing care I received with such commitment and humour.

Brian Pineira, The Filipino nurse who is a valued member of the hospital’s stem-cell research team, but who returns to the wards to do stints in his former role as nurse. It was he who was pushing my bed down a corridor when he learned I was a writer. He brought my bed to a halt and quoted verbatim from Gabriel García Márquez’s ‘Love in the Time of Cholera’: “Age has no reality except in the physical world. The essence of a human being is resistant to the passage of time. Our inner lives are eternal, which is to say that our spirits remain as youthful and vigorous as when we were in full bloom. Think of love as a state of grace, not the means to anything, but the alpha and omega. An end in itself.”

Then there was the nurse who, when replacing my chest bandage, wanted me to breath in deeply. “Puff out your chest,” she said, “like a Robin Redbreast.”

The two ward caterers, Olivia Ellor-Freeman and Lydia Kortey, who brought me tea when I had forgotten to ask for it.

I had visits from family and friends and Deicola Neves repeated his Queen’s Square visit. On this visit he left his guitar with me. Even less able to play with my damaged left hand, it was put to good use by one of the house doctors who would return to my bedside after his ward rounds to play blues music.

I had two wonderful surprises. The Balkan band, Dubioza Kolektiv, visited me when in London on their UK tour and Jeremy Corbyn took time off from being persecuted for daring to speak up for the many and not the few. When he arrived in my ward, there was smiling pandemonium as the nurses, cleaners and catering staff crowded round him for selfies.

I am left with warm memories of those who cared for me, family and friends who visited me, grateful to a cow and a bit angry with horses.

As for the longer-term after effects of my stroke, I walk with a stick and can no longer play guitar because my left hand doesn’t want to wake up. My left leg doesn’t seem to be talking to my brain so I’m always crashing against tables and chairs. I am totally deaf in my right ear and have lost all sense of smell.

When Barry chatted to the patient beside him, a Trinidadian, about memories of their island homes, they talked about their love of the calabash tree, its soft brown bark home to multi-coloured orchids. They told me that these trees, pollinated by bats, grow on hillsides, along roadsides and wherever there are human beings.

The pulp of the fruit has medicinal properties and acts as a remedy for asthma, dysentery and high-blood pressure. It disinfects wounds and is used to treat bruises and tumours.

The NHS is our Calabash tree.

When I was discharged, I left a thank you card with this poem dedicated to my heart surgeon, his surgical team, anaesthetists, the clinical lab who worked out which drug would save me and the nursing/ancillary staff at Barts, Ward 4B. I titled it ‘To my dead Donor’.

My blood pump was stopped

while a machine took over

the job my heart had done

for almost 73 years.

A cow’s pericardium replaced

my narrowed, furred valve

that no longer moved like

a sea anemone’s fronds.

This valve was given without

agreement or consent

so I made a vow to my dead donor

to never eat beef again.

Last time it was a subdural haematoma.

I escaped with my brain re-centred.

That involved an earlier pact

made with myself to act wisely

with attention to my herd.

My plan of action now

begins with breaking through the fence

to arrive in greener pastures.

Since leaving hospital for the third time, I have written about my experiences of the NHS. I am well aware of the importance of its personnel: who they are, where they come from and the skills that have kept me alive. I have tried to draw attention to the privatisation of the health service and its dangers for both health workers and patients. How the attacks on the NHS were carried out to benefit the already rich.

Jeremy Corbyn’s visit to see me took place at a time when he seemed likely to be our next PM campaigning in defence of our public health service.

Note for racists. My brain surgeon was Nigerian, my heart surgeon Egyptian, the chief cardiologist a Glaswegian Jew. Today I count nurse Brian Pineira, the Filipino nurse who quoted Márquez, as a personal friend.

In Aneurin Bevan’s words, the NHS is a health system based on this principle: “No society can legitimately call itself civilised if a sick person is denied medical aid because of lack of means.”

We need to bear this in mind as we fight for our NHS against the privatisers. They are creeping in, and have already crept through, the cracks in our defences. Brian told me what pride he once took in serving food to his patients and how this was a central part of nursing care. Today this has been handed to Serco, who run our prisons and whose annual revenue from healthcare is over £1.4 billion.

Breakfast was tepid tea or coffee, cereal or porridge and toast. As I bit into the damp bread, I could imagine Serco executives meeting to discuss how to cut back their costs to increase their profits. “Let’s start with breakfast.”