In his classic volume of prison letters, Soledad Brother, George Jackson writes that ‘Patience has its limits. Take it too far and it’s cowardice.’

While no one familiar with the life of George Jackson would normally dare contradict the kind of wisdom acquired through extreme adversity and hard struggle, the historic victory of Sinn Fein in the 2020 Irish general election suggests that patience can in politics be more courageous than impatience in pursuit of a people’s and nation’s liberation.

The torturous and tragic history of Ireland is inextricably linked to the crimes of British colonialism and empire. It’s partition in 1921 into the 26-country free state in the south and the six counties of the north, which remained under British rule as Northern Ireland, gave rise to the very ‘carnival of reaction’ that had been prophesied by James Connolly years before partition was established.

The London-controlled province, with its inbuilt Protestant and unionist majority, instantly became a by-word for religious sectarianism and institutional apartheid, wherein the Catholic and nationalist minority were viewed as the enemy within and treated as such.

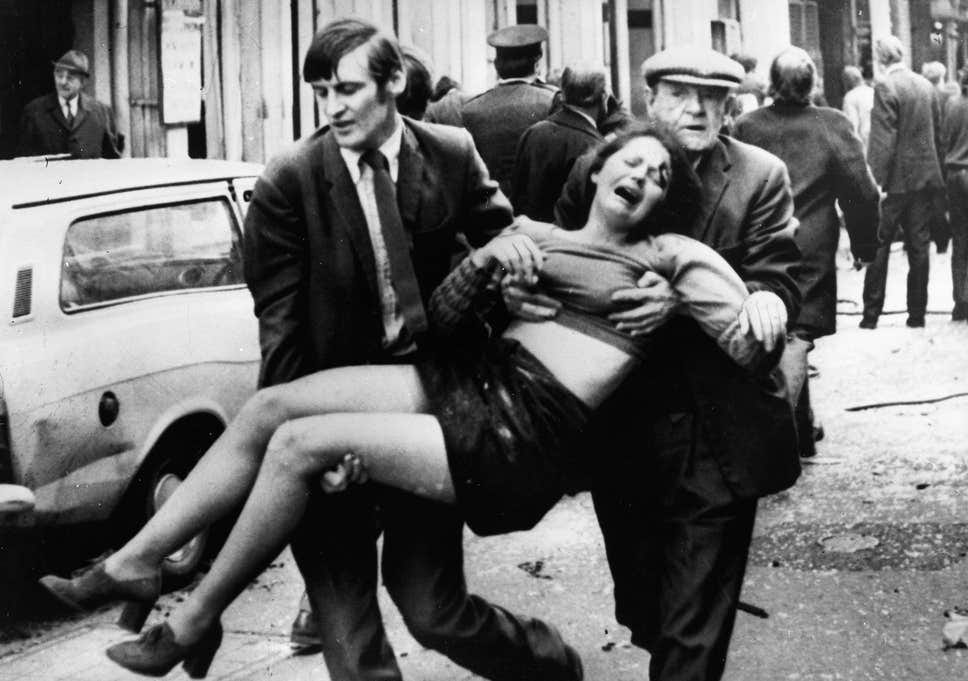

This iniquitous state of affairs gave rise to Irish Civil Rights Movement in the mid-1960s. Inspired by the Black Civil Rights Movement in the US, it met with the same hostility and violence, its members and supporters attacked and bludgeoned by sectarian thugs both in and out of police uniform whenever and wherever they appeared on the streets of the north to demand equality and civil rights for the province’s Catholic citizens. The resulting strife saw British troops being deployed to Northern Ireland for the first time.

Initially there to keep the peace between both communities, the British Army soon became just another tool of anti-Catholic sectarian oppression in the hands of Northern Ireland unionist administration. The end result was the Ballymurphy Massacre of 1971 in Belfast and Bloody Sunday in Derry in January 1972. Both events involved troops of the British Parachute Regiment gunning down unarmed civilians.

Into the picture now came the Provisional IRA and 30 years of conflict known as The Troubles.

The high-water mark of an armed struggle which saw atrocities committed by all sides was for Irish Republicanism the 1981 hunger strike in the Maze Prison, in which ten Irish Republican prisoners, led by Bobby Sands, starved themselves to death in protest at having their political status removed by the British.

The death of Sands and his comrades had an enormous international impact, but even more important than that was how Sands’ decision to contest a by-election in Fermanagh and County Tyrone while on hunger strike, which he won, along with the election of fellow hunger striker, Kieran Doherty to the Dail (Irish Parliament) set in train the direction of mainstream Irish republicanism away from the bullet towards the ballot.

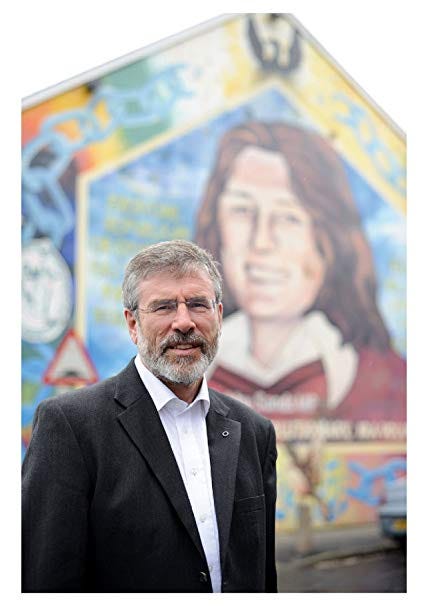

Along with former Derry IRA commander Martin McGuinness, now retired President of Sinn Fein Gerry Adams worked to end the IRA’s armed struggle and channel the struggle through the conduit of electoral politics from that point on.

They succeeded in doing so in the face of harsh criticism from within Irish republicanism — from men and women who believed that armed struggle for Irish unity and freedom was sacrosanct and electoral politics a betrayal, in that by definition it recognised British colonial rule in the north and a truncated republic in the south.

Adams’ decision to pivot his own political focus as leader of Sinn Fein to the south in the wake of the 1998 Good Friday, rather than take up a leading role for the party at Stormont within Northern Ireland’s new power-sharing devolved administration, was informed by the view that the road to a united Ireland runs through Dublin.

The 2008 global financial collapse and ensuing global recession, plunging neoliberalism into a crisis only deepened by draconian austerity programmes imposed across the West with the aim of ensuring that the bulk of the resulting economic pain was felt by the working class rather than business class, has succeeded not in saving the status quo but instead renting it asunder.

In the context of the UK a rising tide of support for Scottish independence and Brexit are the fruits, while in Ireland Sinn Fein, a party which for many years was known as the political wing of the Provisional IRA, has just caused a political earthquake.

It allows even the most sceptical to believe that though there remain political obstacles to overcome, a united Ireland has now taken on the character of an idea whose time has come.

End.