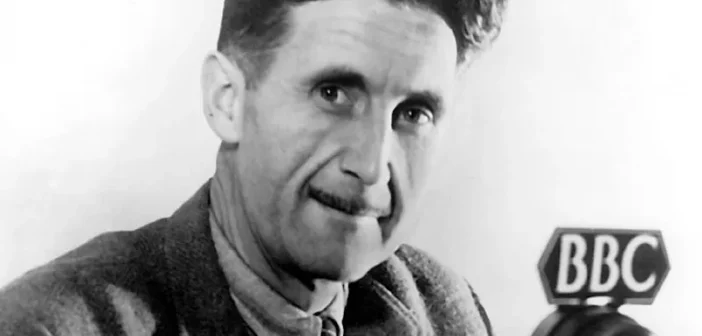

Diana Young writes: For a man who is often described as having died ‘before his time’ George Orwell has had a long afterlife.

His essays on politics and language are re-read in a post-truth age of fake news. His two most famous works, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four remain, for many in Central and Eastern Europe a warning of dictatorship and totalitarianism. In the post-Blair years, the Labour Party reached for Orwell to come to a definition of Englishness and nationalism. But it is his political legacy which is most often fought over. Raymond Williams’ Orwell is a socialist who is outside the organised working class. In Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow (2011) David Goodway paints him in anarchist colours while in Orwell’s Victory (2002) Christopher Hitchens comes up with a figure who looks remarkably like himself, a truth-telling contrarian who is the moral compass for the left. And then there are the multiple works of John Newsinger which include two volumes on Orwell’s politics, interesting for Newsinger’s diligence in showing Orwell to be a Trotskyist after all.i

Most commentators would agree that from late 1936 and his experience of the Spanish Civil War, Orwell was committed to democratic socialism. However, during the Second World War and after, his understanding of socialism shifted and became difficult to pin down. His criticisms of Stalinism, informed by his experiences of the suppression of the POUM in Spain made him a stern critic of Soviet communism. However, Orwell, was also an equally stern and opinionated critic of the British left and especially what he saw as the bourgeois socialists and faddists. One of the areas where Orwell stood in contrast to others on the left was in his opposition to birth control.

Orwell and the English People

In 1947 Orwell wrote the text for a short book in the Collins’ ‘Britain in Pictures’ series entitled The English People. The text of less than 50 pages, including pictures, has the following passage:

The English “have got to retain their vitality… There was a small rise in the birthrate during the war years but that is probably of no significance, and the general curve is downwards. The position …can only be put right if the curve not only rises sharply, but does so within ten or at most twenty years”.ii

Orwell stresses that the rise and fall in the birthrate is linked to the national economy stating that in the growth period of the early nineteenth century they had had an extremely high birthrate and children were used in a very callous way in which the death of a child was “looked on as a very minor tragedy”. By the twentieth century a large family has brought economic hardship where “your children must wear poorer clothes”.iii

To encourage an increase in the birthrate (what he calls the “philoprogenitive instinct”) Orwell, states that the “Half-hearted family allowances will not do the trick…” and that “Any government, by a few strokes of the pen, could make childlessness as unbearable an economic burden as a big family is now… taxation will have to be graded so as to encourage child bearing and to save women with young children from being obliged to work outside the home.”iv

He concludes this section of the text with a focus on economic incentives but then calls for “a change of outlook”. This includes a new attitude to abortion which while “theoretically illegal” is looked upon “as a peccadillo”.v

Birth control and socialism

It is interesting that Orwell, not a man known for his orthodoxy, should focus on birth control as a windmill to tilt at. From the last quarter of the nineteenth century, population control was an early issue in which socialists and freethinkers united. Before the formation of the Social Democratic Federation, Annie Besant had published The Law of Population (1st edition 1877) which advocated birth control. Some activists such as Tom Mann came to socialism via anti-Malthusianism,vi while, the partner of Eleanor Marx, Edward Aveling, was also a strong advocate of birth control. In the socialist press of the 1890s, for example, S. Gardiner defended birth control by pointing out that pregnancy kept women from the social world and political life. “Socialists should teach women comrades,” she wrote, “how to lessen their families, have fewer children and healthy ones, and then perhaps, more women would join our ranks, as they would have more time to learn about socialism.”vii

However, like Orwell, some socialists opposed birth control. There were a variety of reasons, firstly, because it diverted attention from the social question, secondly, because overpopulation could be avoided by “natural” means, and thirdly, because women’s control over reproduction would upset the relationships between men and women and undermine the family structure. Lastly, in a way preceding Orwell’s focus on the joy of sex in Nineteen Eighty-Four, sexual pleasure which may be a result of birth control “was not a true measure of happiness and should not be pursued.”viii In many ways socialists in the 1890s as well as Orwell half a century later, tried to uphold conservative morals as a counterbalance to their radical economic analysis.

Despite this opposition, campaigns for birth control and the legalisation of abortion remained at the heart of the socialist and labour movement. Marie Stopes published Married Love in 1918 and Sheila Rowbotham describes how speakers on birth control went out to Women’s Co-operative Guild groups and Labour Party women’s sections. In 1924 the Labour women’s conference resolved that the Ministry of Health should allow local health authorities to provide birth control information to those who wanted it. In 1927, in contrast to Orwell’s later romanticism of the working class family, a miner’s wife from Cannock in the Staffordshire coalfield appealed to the Labour Party conference for support from the miners for birth control in return for women’s solidarity with the miners during the lockout because, as one declaimed “It is four times as dangerous for a woman to bear a child as it is for you to go down a mine”.ix Thus, by the time of the Second World War there was strong support for birth control and free access to abortion included in socialist planning.

Orwell, class and the politics of the family

George Woodcock, who knew Orwell in the 1940s, claims that his proposals on abortion and birth control were “probably his most reactionary he ever made.”x Although the extracts quoted above came from one of Orwell’s more minor publications he had trailed his view on birth control in his previously published works. For example, in the second part of The Road to Wigan Pier (1936) Orwell creates the bogie with the supposed statement of critics who say “I don’t object to Socialism, but I do object to Socialists” and he goes on to characterise a typical socialist as “a prim little man with a white collar job” and recites a lengthy list of the earnest causes and habits he feels alienates the ordinary person from socialism. Speaking of the 1920s he states that “contraception and enlightenment were held to be synonymous.” Orwell felt that after the First World War, “England was full of half-baked antinomian opinions. Pacifism, internationalism, humanitarianism of all kinds, feminism, free love, divorce reform, atheism, birth control – things like these were getting a better hearing than they would get in normal times”.xi

In Keep the Aspidistra Flying, written in 1934-5 but published in 1936, Orwell has his anti-hero curse the money god and its control over procreation. Gordon Comstock denounces contraception as “just another way they’ve found of bullying us.” It is interesting to note who “they” might be here. Dan Hitchens notes that it may be not just Hitler, Stalin, Big Brother and the money god but also the “prim” socialists caricatured in The Road to Wigan Pier.xii

Finally, in Nineteen Eighty-Four Orwell’s dystopian vision is shown in the Anti-Sex League and the dissolution of his essentially Dickensian ideal of the family when in the future children inform on their parents. Orwell’s view of the singing woman hanging out the washing is presented without irony but comes across as a parody of pure and natural proles. In this eulogy he writes of “the woman of fifty, blown up to monstrous dimensions by childbearing, then hardened and toughened by work till it was course in the grain like an over-ripe turnip. [This] could be beautiful”. She is, to Winston Smith (Orwell) “an idea of resistance to the Party”. Hitchens writes of this passage that “this remarkable moment throws the eugenicists’ worst nightmare back at them. An impoverished woman who has a large number of children becomes the final, ineradicable sign there is something in the world which is bigger than Big Brother.”xiii

Orwell’s socialism

Over the past seventy years there has been a game of ‘What would Orwell have done?’ Would he have been a staunch Cold Warrior or would he have supported the invasion of Iraq? With his views on abortion and birth control we have a new set of questions which amount to: would he have supported the feminists in Poland or would he have supported the legislation in Texas?

For Marxists the role of the family is in establishing bourgeois ideology and the gender roles necessary for social reproduction. Orwell’s view of the family as well as his views on birth control and abortion show scant regard for the bodily autonomy of women and are not so much conservative and Victorian as reactionary and authoritarian. His views on the working-class family and attitudes to sex seem to idealise the working class as somehow more natural and pure compared with the strangled views of the prim middle-class socialists he comes across. There are few Marxist or socialist feminists either in the past or currently who would share Orwell’s views.

And so, Orwell is a dead white, “lower upper middle class”, male who was in opposition to abortion and birth control and eulogised the bourgeois family. His reputation for anti-feminism, homophobia and antisemitism are on record. Should he be cancelled? Orwell, could be an anarchist, feel comfortable with Trotskyists and support the Labour Party but he was hard to pin down because he was not doctrinaire. In a time of intolerance and culture wars we can surely disagree with Orwell without silencing him.

i John Newsinger, Orwell’s Politics (1999) and ‘Hope Lies in the Proles’, George Orwell and the Left (2018).

ii George Orwell, The English People (1947), p41.

iii ibid.

iv ibid.

v op. cit., p42.

vi Tom Man, Tom Mann’s Memoirs (1923), p25-8.

vii Justice, 23 June 1894

viii A. McLaren, ‘Sex and Socialism: The opposition of the French Left to birth control in the nineteenth century.’ Journal of the History of Ideas (37), 1976, p477.

ix Sheila Rowbotham, Hidden from History (Second edition 1974), pp149-50.

x The Crystal Spirit (1970), p205

xi George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (1936), p156, p125

xii Woodcock, opt. cit. p206, see also, Dan Hitchens, ‘Orwell and Contraception’, First Things, April, 2016.

xiii Hitchens, op. cit.