If France really holds freedom of expression as sacred , it needs to reflect on how it can build bridges with its minority communities.

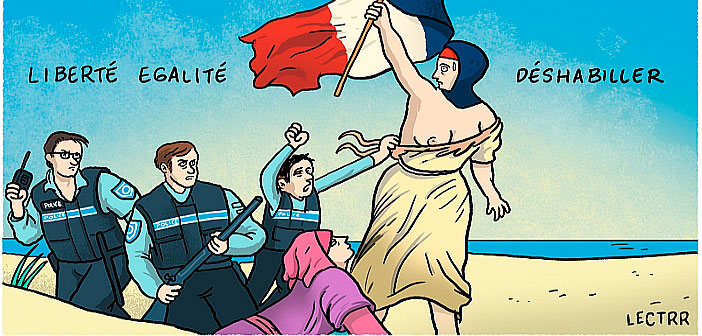

This is just the latest battleground where France’s Muslim population have had their choices scrutinised and restricted by a government that claims to protect the value of freedom of expression. The same heated debate led to women and girls being banned from wearing headscarves in schools, and over the past few years there have been strong calls to extend the ban to universities as well – calls that may well come into effect soon if Valls has anything to do with it.

The danger that Muslims pose to the French way of life is clearly of great concern to the French media and politicians, many of whom have expressed concerns about the incompatibility of Islam with core French values, most specifically, that of laïcité or secularism. Sweeping generalisations are made, with no official statistics or evidence to back them up. But even if anyone tried to look for data, the French interpretation of laïcité would prevent them from finding it.

This is because the French system interprets secularism not only as the separation of religion from the state, but also as an artificial way of claiming equality for all citizens. In an effort to maintain this idea of equality, it’s technically illegal to collect data about ethnicity or religion as we do here in the UK. To do so in France would be seen as a form of discrimination in itself.

If equality is assumed and not monitored – in employment, the police force, stop-and-searches and higher education – that is a huge problem for minority communities. At a time when Islamophobia, police brutality against minorities and concerns about religious fanaticism are at a high, it makes sense to be collecting as much information about minority communities as possible. In Britain in the past month alone, we’ve learned how there was a spike in race hate crime during and after the Brexit referendum; and groundbreaking research has been released on the levels of racial inequality in the UK. How are French authorities supposed to tackle issues that have been identified as being concerns in Muslim and black communities if they only choose to recognise the existence of these communities in exceptional circumstances?

Integration is seen to be a clear cause for concern in France. Along with social exclusion, unemployment and disenfranchisement, it’s often highlighted as a contributing factor in the rise of jihadism. Surely the authorities should be able to explore these areas and collect official statistics to inform their counter-terrorism projects? Newspapers seem to have a very clear idea about the profile of young French jihadis and are quick to reference their origins, their history in the French prison system and their link to religion – and yet the state doesn’t seem to regard it as a priority to try to obtain official figures that may help them to understand the issues that may lead to individuals being radicalised.

And laïcité is not just a problem for French Muslims, it affects all minorities. Schemes and projects that could be targeted to improve integration and equality of opportunity for different racial groups are being hindered.

French politician Nadine Morano caused outrage last year after she described France as “a Jewish-Christian country … of white race, which takes in foreigners”. Many people pointed out that this statement was at odds with the idea of laïcité, but I found it more shocking that she denied the very belonging of non-white communities in France.

Many of its black and Arab communities are descended from inhabitants of its former colonies. Their forefathers fought for the French in both world wars. Even if their families have only been living in France for one or two generations, their relationship with the country goes back much further. And their cultures and religions are not going to be erased simply by banning burkinis or the hijab.

I’m often told that the colonial history France has with Algeria is no longer relevant, and that things have long since moved on, but my own experience tells me otherwise. At a house party in Paris one French guy asked me what my origins were. When I told him of my Algerian roots he responded, “Don’t forget, we used to own your country.” On a different occasion I had a guy drunkenly explain to me that if France had never colonised Algeria my family and I would still be sitting on the floor eating with our hands, and that France had brought civilisation to the “savages in north Africa”. I’ve been singled out by the police as a white colleague next to me appeared invisible to them. The list goes on, and I can’t imagine what it would be like if I were more visibly Muslim.

While the nation feigns blindness to its diverse communities, tensions between them and the rest of the population are steadily increasing. With the rise of the far-right Front National and increased concerns about immigration, the pollsters Ipsos conducted a survey to assess racist tendencies in France. For simply asking questions related to race they were condemned, and even threatened with being sued.

Until recent decades, many Latin American countries promoted “mestizo” or “mixed” national identities that claimed to recognise diversity but in reality didn’t recognise the significant black and indigenous communities, or allow them to claim their rights. The ideology of mestizaje in practice serves to assimilate Afro-descendants and indigenous peoples, denying their cultures and ignoring their historic contributions to their nations.

It feels like a similar thing is happening in France. Laïcité should in theory promote social harmony between different groups in a multicultural, multi-faith society; but in practice it’s being invoked as the reason for policing Muslims’ day-to-day lives and suppressing their ability to express their faith.

If France really does hold freedom of expression as a sacred value then now, more than ever, it needs to reflect on how it can build bridges with its minority communities and bring about a more tolerant interpretation of secularism.