As the Nobel winning writer of a recent song celebrating the joys of Santa Clause once wrote: ‘the times they are a-changing;’ to which I must regretfully add; but only for the worse. It is a sad and sorry state of affairs when the former century’s crucial statements are potentially sacrificed for the momentary comforts of commercial immersion and assimilation, as if all of the urgency of the past strains the throat as it searches for the saccharine. If those who once spoke the old truths continually (and in as hard a rain as the ones we are currently suffering), are no longer willing or perhaps able to speak them, to whom exactly can we turn to make or mark the vital utterances and critiques needed in order to rattle politics’ skeletal boat?

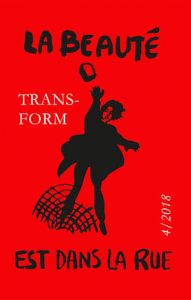

The answer can be found in issue 4 of Transform, a Journal of the Radical Left, the latest publication from Public Reading Rooms. Bearing a cover Illustration of a slogan proclaiming La Beaute est dans la rue, the issue celebrates the fifty year anniversary of 1968 with a similar fervour and revolutionary zeal of the events of that famous year as they and the people behind them struggled to enlighten and initiate the proper meaning of a new world order, before it was replaced by a far more abusive version.

The centre piece (or near enough to dead centre in fact, coming as it does on page 64 of a 159 page selection of essays with notes) is Ken Livingstone’s account of the labour party’s struggles for self definition in the wake of the postwar Atlee government and the explosion of change and rage at the modern oppressions mounted across the world in that later, seminal summer. It was this period of renegotiating relationships with our leaders and representatives that effectively shattered the culture of personality erected around the sometimes shattering conservatism of Sir Winston Churchill – eerily if not as charismatically echoed today with our endless parade of the lacklustre and lily livered, the unrepentant and the downright corrosive. The innovations and concerns shown by socialism as it used to be practised gave the young Livingstone hope and formed the bedrock of his own politicisation, with 1968 marking the energy and commitment he later plied into London as leader of the GLC and Mayor.

At a launch night event for this publication at the LSE, Livingstone spoke of how the days of his youth were marked by the guarantee of employment and socialisation, regardless of one’s individual leanings and the welfare state and burgeoning NHS were shining exemplars of the protectionism the state could offer. When the strictures surrounding these advances began breaking down, the cracks were self evident and a newly politicised generation began staring and indeed prising those fractures apart. As student and racial protest staged their outrage against less generous regimes and climates the era of hope promised was therefore put under considerable pressure, proving to all the shallow limits of its durability. Having proved himself along with Tony Benn to be one of this country’s most valuable, sincere and it has to be said, misunderstood politicians, what Livingstone says in his essay is, polemics aside, a call to what Harold Pinter described in his Nobel speech as ‘the simple dignity of man.’ Judaism is not Zionism as I understand it, as a middle class British Jew in the same way that being German did not automatically make you a Nazi. The very things that have caused perturbation for Livingstone recently and Jeremy Corbyn in his wake, lay at the heart of all of the pieces in this volume; chiefly how do we assign and subscribe to the idea of a spiritual and political homeland without betraying the necessary edicts involved in consolidating it? It s not anti-Semitic to support Palestine; it is anti-oppression. Our current confusion of associations around the literature and practise of revolt are what the Transform contributors are attempting to unravel.

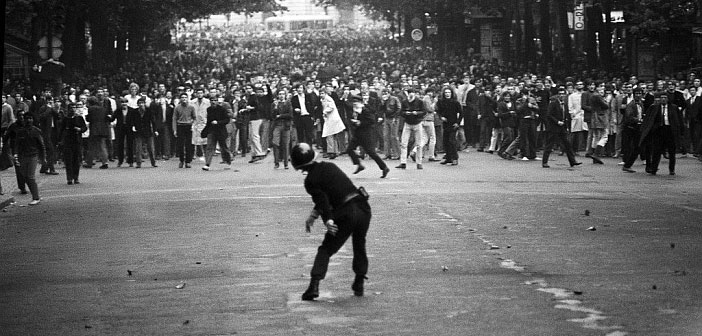

Livingstone’s essay is called Bringing the 68 Spirit into the Labour Party and is concerned with detailing the uniting of values necessary to affect change. You do not win an argument by committing acts of war against another people in the name of God and you do not attempt to silence races and generations because they question the dubious merits of your leadership. Hiding behind the frenzied protocols of Thatcherism and its successive wing of political ugly ducklings is a further subversion of the story. The oppositions of the students in Paris, echoing their antecedents at the gates of the royal palace en route to the Bastille, or those eloquent battles in Kent state were observed at a distance in this country. The strongest opposition coming from That Was The Week That Was and the machinations of Private Eye. As hordes harranged against the jingoism of Viet Nam in the States and Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated, we had David Frost and Lance Percival ripping off Peter Cook and essaying calypsos. In short, the extent to which this country has ever rolled it’s sleeves up in the official sense of the word is woeful. The state’s attack on the striking miners is one such example of officialdom rallying its forces, but for the wrong reasons. Sedition is not safeguarding. And so the virulence of global resistance is what Livingstone and the other contributors in this volume are calling for.

There have of course always been underground artists and activists, too legion to mention, who have sought to affect the right sort of change, such as Journal Editor and General Secretary of CND, Kate Hudson has proved, but I believe the point here, under the banner of the radical left, is not to preach to the already converted but to try and wake up the sonumbulant centre.

Michael Wongsam studiously outlines the problems within the American system in his opening essay, which goes to show in a clear sighted and step by step way just how racialised American politics has become since 1968 and of course the two hundred years leading up to it. The senatorial elections of December 2017 led to the near appointment of the Trump endorsed Roy Moore, a white ultra conservative facing a near Weinsteinian level of sexual accusation. His defeat was as slim as his conscience has proved to be and highlighted how the fight between the black and white vote since the end of Obama’s tenure has become more hysteric than anyone could have previously thought possible. While Trump talk motors on the fact that the US actually had a black President for any amount of time is to my mind at least, practically forgotten. Or at the. Very least in danger of being wiped from the collective memory altogether. It is this same lack of honouring or marking important advances within society over the last fifty years that features in this and All of the included essays. Something crucial has been lost. It was epitomised by the spirit that set 1968 apart as a catalogue year, in which the ensuing product was the price of freedom and liberation on both grand and domestic levels.

The ever gathering tensions between the constitution and the federal government are expertly outlined by Wongsam as he fully details the extent of the betrayals at hand. It as if the system has always been weighted against the disenchanted and the disenfranchised. When a Supreme Court decision in 1883 ruled that the civil rights act of 1875 was erroneous in granting blacks equal rights, the pressure was on for the New Deal era of 1932-1964 to ring the changes set about by the advanced of Abraham Lincoln and the successive generations of black leaders and activists. Perhaps no system yet made by man can function at its appointed or expected level, especially when advances in society and politics are immediately rescinded by reactionary missteps.

The die has been cast indeed and Wongsam shows just how far the racial scales have swung. With the US having 5% of the world’s population and 25% of the world’s prisons, the mass incarceration of black men in America leads to a frightening 40%. If that imbalance of prejudice, destiny and design doesn’t call for the rapid gathering of tensions and for a similar explosion of resistance as that of fifty years ago, then God knows what does. As Brexit looms and the immigration wars can be almost heard catching flame the lessons of the past have not been learnt or indeed heeded.

Jude Woodward’s essay on the legacy of the war in Vietnam which of course fully defined itself in 1968 is a powerful rendition of the situations and circumstances that spread like fire on oil. Dr King is quoted in his December speech of 1967, which enhances Wongam’s essay succinctly:

‘We were taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them 8000 miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in Southwest Georgia and East Harlem..’

The more one reads the greater the chill spreads and the harder it is to believe that something isn’t coming. Are we truly that detached from our own history to deny it? As the radical left grows more severe for reasons made necessary by contemporary beligerance and the near abstractions of the Trump and for that matter B. Johnson era, the promise of danger grows ever keener. China’s rise as the predominant superpower in 21st century global economics and most other areas in the decades leading to it, achieves a shrill echo with the reasons for America’s involvement back in the day and Woodward closes this essay with the call for all in opposition to stand with the east against the new way of American oppressors, making it;

‘Today’s decisive line in the sand of the same struggle for which the Vietnamese fought and died and inspired the world in 1968.’

Woodward states ‘that much of the radicalism spawned by the successes in Vietnam was spent decades ago.’ This theme is picked up by Chris Hazzard MP in his essay Rhythm of Time. By stating that the seeds of the tree of liberty pass from America to France and fall in Ireland, he incapsualtes how own career of resistance as a member of Sinn Fein, opposing English oppression and defining the struggles between Catholic and protestant throughout the troubles and into the ominous now. In this sense 1968 is not just a moment in history to be filed next to the miner’s strike, the peasant’s revolt or any singular effort to revoke calamity, but is in effect, still here. The starkness and musculature of ’68 is always happening in one way or another, it’s eyes peering from the smoke, or glazing moonlike from the dark.

From the Irish people’s rebellion of 1798, to the Fenian Proclamation of 1867, through the ‘tireless agitation’ of James Connolly and Jim Larkin, events within Ireland in all of its struggles have put it into practise that fight for settlement and recognition. The Volcano has continued to erupt but it’s as if the world today only has time to see the boiling bubble of froth closest to them. Hazzard describes the Good Friday agreement as a new and peaceful way forward based on equality and respect, but the sudden swing to the right as if one of that endless tower of turtles had been extracted to reveal how easily we can fall for or believe in the spurious and untested frictions of tin pot tyrants and despots has called for a renewed sense of urgency and determination to keep the resistance sharp and aware of the dangers before it. Revolutionism must be ready to take hold of the powers that be(nd).

Phil Hearse skilfully details the socialist students federation at the time of the wave of protests in 1968, just as Marina Prentoulis sets out the effects of their actions in Southern Europe in the years that followed, while Francisco Dominguez examines the effects of Bolshevism on Latin America with refinement and elegance. These historical perspectives reveal the depths of knowledge and experience behind the figures and movements that inspired protest and who continue to feed it as the students who manned,womanned (sic) and peopled the barriers at that fiery time become the lecturers, activists and authors crying with fear and anger at the injustices we continue to face. When Katy Day and Rebecca Wray report on the advances and struggles faced by fourth wave feminism, we see how the violence faced by those who opposed it with physical and academic intelligence, still resides in the battles raged within gender politics. By examining the prevailing issues of segregation and supposed inclusivity we see once more and continue to see how 1968 is and has continued to adapt as a spiritual, social and political force; a means of realisation and reaction that can be called upon in the most stringent emergencies and testing or tying of times. The female struggle against the prevailing male climate drags relationships, families and individuals to the battlefront and the statistics and examples quoted are frightening dischords to what I suspect the uninformed still see as society’s simple song.

Philippe Marliere closing essay Can Left Populism work in France? virtually works as a one phrase argument, but demonstrates how a small opposition can build into a larger force, by charting the progress of Jean Luc Melechon’s Unbowed France party in the wake of Macron’s inspiring presidency. This catalogue of hope after the devastations listed in the previous entries not only takes us back to the literal homeland of reactionary action, but reveals how this journal has proved itself invaluable. Having given his life to the politics of change, Ken Livingstone’s conclusion at the launch event was to call to all of those still here who were there in 1968 and who actively have a stake in its ramifications, to not sit back in the comforts of restrictions of age, and reflect or eulogise in fear of the young, but to rather return to the fray and get involved still, working with the successive generations to revive and remind the shallow times in which we are all presently living, that there is a deeper and if it can be so, ‘sturdier’ river flowing hair beneath these most unsettled of lands. At quiet times you may feel the tectonic of history gather beneath you, just as you may hear the rising notes of liberty in more obstructive musics. 1968 changed so many things, areas, aspects of life and people. The right wing movements across the world from Thatcher to Mugabe have sought to set it back again. It is now time for those whose minds are clear enough to allow for the full range of free thinking to see through the smears and locate the fresh steel in the cloud. Hard rains are still falling, but if we resist them, we may still get to bathe and transform.

The streets where they rallied are still split in spirit. Storm again and fresh water may once again fill the cracks.

Remembering 1968 – La Beauté est dans la rue is a Transform special issue reflecting on the year that was a turning point in history.

Remembering 1968 – La Beauté est dans la rue is a Transform special issue reflecting on the year that was a turning point in history.