Laura Parker and Andrea Pisauro write: Over the course of just a few months, the coronavirus pandemic has brought about a considerable loss of human life, a severe and ongoing public health emergency and significant disruption to virtually all human activities across the planet. Far from being suppressed, it appears extremely likely that the epidemic will accompany our lives for many months to come. Its implications will profoundly reshape the economic, political and cultural institutions which govern society.

Due to the uneven spread of the epidemic amongst different countries and the differences in their governments’ response to it, it is impossible to predict exactly how this crisis will unravel. However it is possible, some three months after the beginning of the epidemic in the UK, to draw the first conclusions about the UK governments’ response and how it compares with elsewhere. It is already clear to those who have had the chance to scrutinise the UK government’s actions that these have been characterised by catastrophic errors and a staggering level of complacency. A tragic farce which will have cost the lives of thousands of citizens and pales in comparison to the more effective responses of most other European countries.

In a symbolic coincidence, the coronavirus epidemic officially arrived in Britain on the 31st of January, Brexit day, when two patients in Newcastle tested positive to the COVID-19 test, upon their return from a trip to China. The news broke on the cover page of most newspapers alongside the celebration of Brexit. Unlike Brexit, COVID-19 related news has not left the front pages since then. At the time of writing (1 May), some 177,000 people are known to have been infected in the UK and 27,510 have died, although it is known that both numbers significantly underestimate the actual extent of the virus’ spread.

It should have been clear of course that ‘exceptional’ Britain would be given no special treatment by a virus. Viruses have no respect for British exceptionalism; they know no borders; they make no distinction on the basis of passport or race. They only know how to reproduce themselves in the human body and there is only one human race – whether it is in Britain, China or anywhere else.

Yet for almost two months the UK government ignored the alarming news breaking first from China, where a city of 10 million people was locked down on January 23rd, and then from Europe, where northern Italy experienced a severe outbreak from February 20th.

It now sounds almost incredible but until March 16th, the government’s strategy was merely to “mitigate” the spread of the coronavirus, following a protocol for a flu pandemic developed in 2011, despite the deadliest flu estimated by some to be up to 30 times less deadly than COVID-19. This was implicitly admitted by the government itself, in its coronavirus action plan published on March the 3rd. This plan provided details of a 4 phased response which aimed to Contain, Delay, Research and Mitigate the impact of the virus, without ever mentioning the need to suppress its spread.

Despite subsequent protestations to the contrary, and an attempt to suggest that attaining so-called ‘herd immunity’ was a by-product, rather than a strategic aim, it is clear that the government’s strategy was indeed based on achieving herd immunity. That is, allowing the infection of a considerable proportion of the UK population, which would then be assumed to be immune in the long term – something which has to date not been confirmed by any scientific study. This was made clear in one of the daily, live briefings by Chief Scientific Officer Sir Patrick Vallance, on March 13th.

The previous day, the study from Neil Ferguson’s team at Imperial College London was first discussed in a meeting of SAGE (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies), the scientific advisory committee that informs the government policy. It predicted that in a best case scenario, under the mitigation strategy pursued by the government, NHS surge limits for “both general ward and ICU beds would be exceeded by at least 8-fold” and 250,000 deaths had to be expected.

This was not the highest estimate for the death toll which was likely under the government policy. Reuters reports that an assessment produced by SPI-M (the group of scientists modelling the spread of the virus) on March the 2nd implied 500,000 casualties. Widely discussed death estimates on the news in the first half of March ranged from 100,000 to 300,000. We know now from multiple sources that the government knew that these death tolls were likely and to be expected under their policy.

For precious weeks, the Government had relied on the assumption that stopping the contagion was impossible – despite China having done precisely that already at the time. It had been ready to accept that a significant proportion of the population would be infected and that there was little to do about the fact that up to one hundred thousand people might have died as a result. That this was possible beggars belief.

The Government has made much of the fact that its strategy is “science-based” but as many critics have noted, eminent scientists among them, this should not be understood as a guarantee that everything it has been doing, or seeking to do, was therefore ‘objectively right’. As is now becoming increasingly clear, some of the scientific assumptions underlying the government initial approach turned out to be deeply flawed.

To begin with, as noted earlier, one of its first and most grievous mistakes was to approach COVID as if it was a flu. It is not. Even in the most conservative estimates, its mortality is at least 10 times higher than the worst flu. And it could easily become 30-40 or 50 times higher if hospitals are saturated by patients of all ages who need ventilation machines to breathe for them for days or even weeks, as we have witnessed in hospitals up and down the country and the world over.

The idea of nudging people into reducing transmission, for instance by mild suggestions that they wash their hands and sing happy birthday twice, was also fundamentally flawed. The point of nudging is making sure people do something without really being aware of it. If the desired outcome is in fact to bring about major changes in lifestyle, it is fundamental that the public has a deep level of understanding and awareness of what is at stake and why it is important to abide by what have to be very clear instructions, not mere suggestions. Quite clearly, those very clear instructions took too long to arrive.

Another deeply flawed notion, repeatedly mentioned throughout the initial phase of the crisis, was that people get fatigued if shut down measures are adopted too early. Behavioural scientists who study motivation and fatigue know well that there are so many different factors that are completely beyond a government’s control which can determine if people are fatigued. 629 behavioural scientists, including one of the authors, wrote an open letter to the government in mid March, expressing their concern that the invitations to “carry on as normal” were undercutting the sense of urgency the situation required.

Indeed the initial strategy was scientifically so weak that it is hard to accept that it was suggested by any scientist at all. On March 15th, when the government had not yet instructed serious social distancing measures, a Harvard Professor of epidemiology made the obvious point that the “herd immunity” argument was good for satire but was not a serious strategy that any government could contemplate in fighting COVID-19. “We talk about vaccines generating herd immunity, so why is this different? Because a virus is not a vaccine” – the coronavirus causing COVID-19 actually kills people. Similar arguments were put forward on the same day also by the British Society for Immunology.

Two key scientific advisers allegedly influenced the government’s resistance to enforce social distancing measures, despite such measures being in place in most European countries: Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty and Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Patrick Vallance. Is it credible to believe that they were unfamiliar with these arguments? It is not.

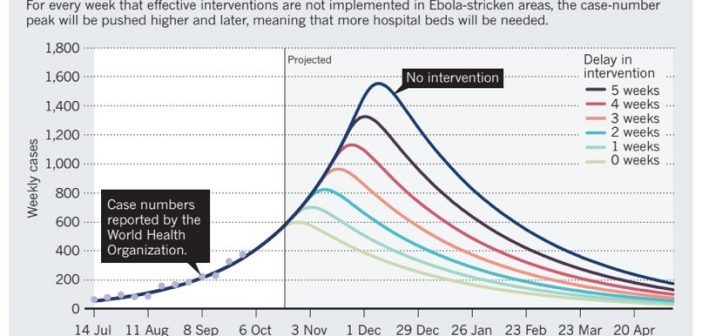

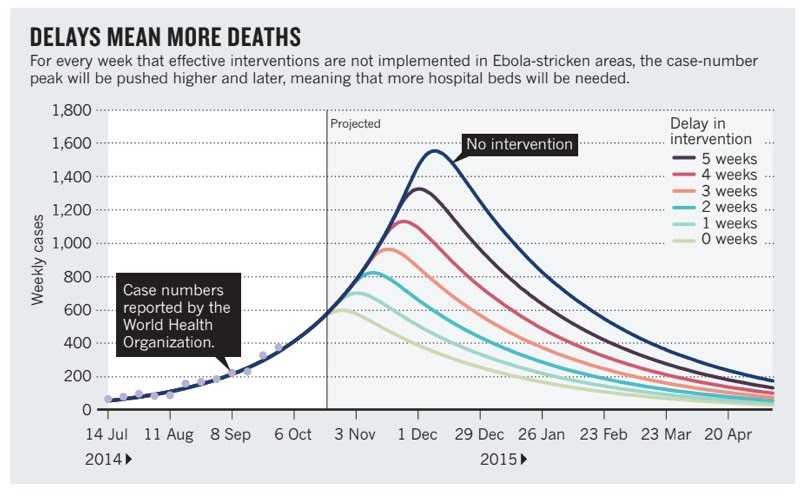

The chart below is from a paper published in Nature in 2014. It is Chris Whitty’s major success story from when he was Chief Scientific Adviser for the Department for International Development. In the article entitled “Infectious disease: Tough choices to reduce Ebola transmission” Whitty advocates decisive and quick interventions, arguing that “hesitation is more dangerous than trying out potentially ineffective methods”. He suggests that contact-tracing, nudging appropriate behaviours and isolation of patients with symptoms is not enough and that a strong intervention to encourage social distancing by voluntary sequestration in government built facilities must be a priority. “We invite critiques and suggestions, but must act swiftly. Further delay will result in more infections and deaths, and only sabotage future efforts” he wrote.

Did Whitty really believe that what was urgent and imperative in 2014 in Sierra Leone was not urgent or imperative in the UK in 2020? Are British citizens the only ones affected by behavioural fatigue in his opinion? Were further delays not causing more infections and deaths for the British public? Of course Whitty knew very well that drastic measures were required to suppress the spread of the virus. Except that the government’s aim was not suppressing the spread of the virus.

This is where the Government hiding behind the shield of science stops being a credible and adequate defence of the choices it has made. Ultimately scientific advice to politicians is just that – advice, informing the decision-maker about the likely consequences of the different options they might pursue. It is how this scientific advice is interpreted by politicians and how they weigh the likely consequences of each choice against other factors which count. This is a matter of policy and policy only, based on political judgements and priorities.

In the case of the COVID-19 emergency, it was the government’s political judgement to initially choose a path of minimal intervention. Even more worryingly, a number of elements suggest that, to a significant extent, it was the government’s priorities shaping its scientific advice, rather than the other way round.

Dominic Cummings’ participation in the SAGE meetings, alongside Vote Leave data scientist Ben Warner, is extremely concerning. A supposedly independent scientific advisory group needs not seek the opinion of the most influential aide to the Prime Minister, in formulating its independent advice. The government has vehemently denied a recent Sunday Times report quoting Cummings saying during a cabinet meeting “herd immunity, protect the economy, and if that means some pensioners die, too bad”, but there can be little doubt that Cummings, a self proclaimed science-lover, has been extremely influential in shaping the early phase of the government response.

So clearly defined were the government priorities at the time that the Prime Minister – whose communications are frequently (deliberately) vague – expressed them quite clearly himself as early as in February. On the 3rd of February, Boris Johnson explained to an audience in London, during a celebratory Brexit speech, that in the face of a global pandemic, the UK could make a profit by avoiding lockdown and becoming a “supercharged champion” of global free trade. It is worth quoting extensively the Prime Minister to understand his political judgement:

“There is a risk that new diseases such as coronavirus will trigger a panic and a desire for market segregation that go beyond what is medically rational to the point of doing real and unnecessary economic damage, then at that moment humanity needs some government somewhere that is willing at least to make the case powerfully for freedom of exchange, some country ready to take off its Clark Kent spectacles and leap into the phone booth and emerge with its cloak flowing as the supercharged champion, of the right of the populations of the earth to buy and sell freely among each other. And here in Greenwich in the first week of February 2020, I can tell you in all humility that the UK is ready for that role”.

It is worth also emphasising that this policy of championing free trade in the face of a likely pandemia was presented during a celebratory Brexit speech. Indeed “unleashing” the country’s potential in global trade is an integral part of the government strategy in rewriting its trade relationships in light of Brexit. No wonder that the suggestion to prepare for a likely lock down, proposed by Professor Ferguson in a SAGE meeting in January (two weeks before the Brexit speech) was dismissed by some ministers as linked to some “post-apocalypse movie”, as reported by the Sunday Times.

In a similar vein, more than a month later a senior source in the UK government labelled as “populist non science-based measures” the lock down just ordered by the Italian authorities. These were just the first and the last of a number of dismissive quotes from ministers, covering the period from the end of January to mid March and reported by a variety of sources. Illustrations of a widely shared complacency amongst the politicians in charge of the country who for more than one month were refusing to engage with the dreadful facts presented to them by scientists. Viewed with alarm at the time by scientists, quotes such as that from Conservative MP Rob Roberts (below) will now be seen with horror by all people in the UK.

There has of course since this point been a change in strategy by the Government – mostly as a result of the lobbying of a large part of the scientific community. This included several letters from different groups of scientists questioning the scientific basis upon which the Government was giving its advice. The critical paper written by the team at Imperial College – which was discussed on 12 March, although only published on 16 March – was also fundamental in steering this change of direction.

This intense pressure from the scientific community was accompanied by what is thought to have been an unprecedented step by Buckingham Palace, announcing that the Queen would cancel all public engagements for the following week “as a sensible precaution”. There were also statements of criticism from those hostile to the government from within the Tory Party, including Rory Stuart and Jeremy Hunt, two former Tory Party leadership candidates, and the pressure from devolved governments who consistently anticipated measures then taken by the UK governments. Ultimately the shift in policy was also the result of international pressure, with President Macron threatening to close the border with France and the WHO raising increasingly explicit concerns about the lack of action in the UK.

But still, there followed 11 days from the Imperial College report to implementing a lock down on March 23rd. When this did come, it represented a gigantic u-turn for a Prime Minister who was recorded live on March the 3rd congratulating himself for having shaken hands with potential coronavirus patients – quite possibly one of the occasions in which he might have caught the virus himself which resulted in his ending up in intensive care, from which luckily he recovered in mid April. Yet the government still denies any u-turn and in a press conference one month later, the first since his recovery from COVID-19, the Prime Minister continues to repeat his soundbite claim that his government took “the right measures at the right time”. A comparison with other European countries shows quite clearly that they did not.

Looking at the five largest European countries – Germany, France, UK, Italy and Spain – which are relatively comparable in terms of population (83, 67, 67, 60, 47 million people, respectively), it is possible to highlight few key comparisons and draw some preliminary conclusions about the relative effectiveness of the response of different governments in tackling the coronavirus pandemic.

The UK was the last among these countries in announcing a lockdown, on March 23rd. Italy did so on March the 9th, Spain on the 11th, France on the 17th, Germany on the 22nd. Even accounting for the different start of the epidemic, the UK locked down 15 days after the third COVID-19 deaths, compared to 9 days for Germany, 10 for Spain and 14 for Italy and France. Indeed the UK arrived last in implementing virtually all containment measures compared to all EU countries, both when considering the absolute date of the announcement or when considering the date relative to the onset of the epidemic, as reported by a comparative analysis published by Politico. This delay in relative terms in implementing measures to suppress the transmission of the virus was particularly appalling: not only did the government not learn anything from the lessons from its nearer neighbours, but in fact it ignored “the facts on the ground” in its own country for longer than any other government in Europe.

This delay brought serious consequences, allowing a quicker spread of the virus. At the time of writing the UK is the third country in Europe by the number of identified cases of COVID-19, following Spain and Italy. Yet because the lockdown here has started later, the number of identified cases in the UK is growing more rapidly than in any other European country, overtaking in the last few days France and Germany. It looks likely that the UK might end up being the first or second country in Europe by the number of COVID-19 cases, both in absolute terms and in relation to the population, where only Spain (and Belgium) may fare worse.

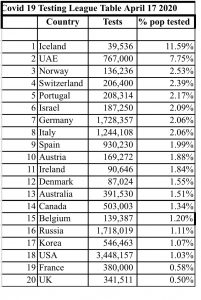

The situation may result in being even worse than that. The number of positive cases is, as a matter of fact, strictly dependent upon the number of tests for COVID-19 administered, as a positive case can only be identified if tested. Therefore the more tests a country administers, the higher the number of cases it will identify. Whilst not all European countries systematically release data about the number of tests performed, a snapshot of the situation from the 17th of April, tweeted by ITV journalist Robert Peston, shows the UK tested less both in absolute terms and in relation to the population than all other four major European countries and several other European ones. The rush to increase testing to meet the 100,000 target by the end of April set by the government has also increased the number of cases detected per day, despite the fact that the epidemic is past its peak.

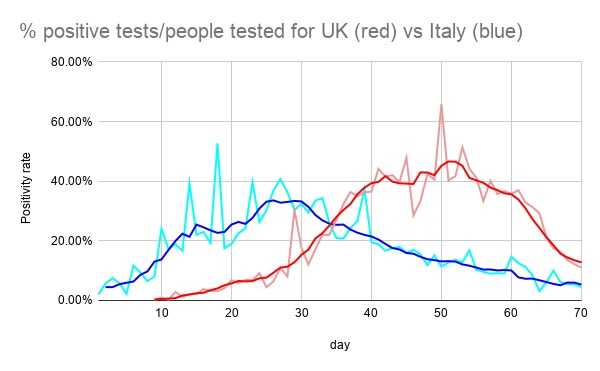

A better indicator of the spread of the virus in a country is actually the ratio between the number of positive cases identified and the number of people tested. If the criteria to test suspected cases do not change too much over time, the higher this ratio, the higher the proportion of the population that is likely to be infected. Its variation over time estimates the spread of the infection. Comparative data from Italy and the UK show quite clearly that the peak arrived in the UK two to three weeks after Italy but also that during the peak, the proportion of positive tests in the UK was higher than in Italy, suggesting a higher number of people were infected overall in the UK than in Italy despite the pandemic having arrived in the UK later.

Percentage of people who tested positive in Italy (blue) and UK (red). Day 1 is the 21st of February. Light colors represent figures reported daily, dark colours represent averages smoothed and weighted on the number of tests. Number of people tested for Italy is interpolated based on the number of tests on early days when official figures were lacking.

The thesis that the epidemic spread more in the UK than in any other European country is confirmed by the official statistics reported by each government – which indicate that the UK is going to be the country in Europe experiencing the heaviest COVID-19 related death toll. These numbers are certain to be lower than the true figure as reported COVID-19 deaths require performing a test to confirm the presence of the virus which almost certainly will not happen in all cases. Whilst a certain degree of under-reporting is happening in all European countries, once again the UK appears to be doing poorly, both in absolute and relative terms, compared to its neighbours.

A recent analysis from the New York Times showed that COVID-19 deaths in the UK during the peak of the epidemic accounted for only 66% of the excess in mortality during this period (calculated by the difference to the average mortality in the same weeks over the previous three years) with more than 10000 deaths unaccounted for by the official statistics – a higher difference than Spain, France and Germany (data from Italy were not reported in this analysis). The Financial Times came up with an even higher estimate of more than 23 thousand deaths unaccounted for, by looking at the relationship between the official statistics and the trends in excess mortality. It was also because of the increasing discrepancy between the official statistics and the results of independent analysis that on the 29th of April the government decided to retrospectively include 4 thousand COVID-19 related additional deaths outside hospitals, a figure which is almost certainly underestimating the number of people who died in care homes alone.

These continuous changes in the reported statistics, combined with the lack of details on the number of patients hospitalised and self-isolating at home (data which is available in other countries), and the refusal to publish the minutes of SAGE meetings, has contributed to a widespread perception of a lack of transparency of the government about the handling of the emergency.

A quicker response from the government would have certainly saved thousands of lives. We can see that clearly in countries like Germany, where the virus arrived relatively late compared to Italy and Spain and where a prompt reaction from the federal government, combined with a strong national health service, has enabled the number of deaths to be limited significantly.

It is also worth emphasising that contrary to the Italian, and to some extent Spanish, governments, which found themselves discovering at the end of February outbreaks which were very likely to have started developing since mid January, the UK outbreaks are very likely to have developed precisely in those precious weeks in which the government lingered with its herd immunity approach. Furthermore, whilst the Italian government immediately created a red zone blocking free movement around the towns where the first cases were detected (later expanded to include all of northern Italy and then the entire country), no significant measures were taken by the UK government when the first cases due to local transmission were detected, at the beginning of March, nor were airports significantly monitored in the previous weeks.

The handling of the emergency remained poor even after the government implemented its policy u-turn. Downing Street knew that the NHS would struggle to increase capacity in case of a pandemic. Four years ago, Operation Cygnus, a simulation exercise in preparation for a pandemic flu, revealed that the NHS would face a shortage of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Despite knowing this since 2016, the government failed to scale up production and many hospitals were left waiting for shipments from overseas, forcing many workers to literally risk their lives to keep treating coronavirus patients – more than 100 NHS workers have died since the beginning of the crisis.

A ridiculous series of excuses was provided by the government to justify its failure to join an EU joint-procurement scheme for vital ventilators, in mid March. Almost embarrassing was the way in which the government managed to meet its own target of 100,000 tests per day by the end of April. To do so the Health Minister changed the way tests were counted by including in the figure 50,000 tests which were frantically sent to the homes of people who had booked them online, some of whom members of the Conservative Party invited through an internal newsletter, without even waiting for the tests to be returned. Many will not be returned for days, but the minister can claim to have met a target that Germany hit several weeks ago without any such tricks.

Whilst the UK has created more beds, and the Government has been keen to publicise the way in which it has worked to ‘protect the NHS’, increasing hospital beds is not the same as creating full additional capacity – given the failures outlined above to manage testing or ensure adequate safety for those working in hospitals. Responding to Covid requires a holistic approach which encompasses far more than physical infrastructure. The Nightingale Hospitals risks being a cruel monument to monumental failures, left empty because it was built without sufficient equipment for the most severe cases and in any case without sufficient staff to service it for the cases which could be treated.

Nowhere can the need for a holistic approach be better seen than in social care. Long the Cinderella story of care in the UK, the tragedy still unfolding in care homes for the long-term ill and elderly is one of the greatest indictments of long-term state neglect and under-funding of social care services. A highly fragmented ‘system’, in significant part privatised and historically poorly regulated, it is almost universally reliant upon very poorly paid staff many of whom at the best of times are not enabled to do their jobs well. Now, in the worst of times, stories emerge daily of care staff working long days with makeshift aprons and homemade face-masks their only protection.

Belatedly included in death statistics only in the last few days, it is clear that care homes are one of the major epicentres of the pandemic, in the UK as elsewhere. The need for a fully funded, National Care Service, must now be abundantly clear to all. This must be one of the major political lessons to be learnt from Covid in the UK, and must remain a key plank of any Labour Party policy programme going forward.

Many other policy lessons must be learnt – and there can also now be no doubt that all of this will have to be the subject of a comprehensive, independent inquiry. This must be initiated as soon as it is practically possible: it is vital that lessons are learnt real-time. There can be no ‘waiting for Covid to end’ as, at this stage, we have such limited understanding of when and how it might ‘end’. The risk of a second peak in a number of European countries remains. No successful antibody test is yet available and there is limited evidence about the degree, or longevity, of any immunity acquired by those who have had the virus. Meanwhile, there is a clear – and in some places, including Brazil and Ecuador – horrific and rapid scaling up of the levels of infection beyond those regions of the world where it first originated.

An inquiry must look at the composition and role of government scientific advisory groups, and the role of political advisors within them. What has been the role of behavioural science in determining the UK’s early response? Was it really behavioural science or actually the exaggerated libertarian instincts of Boris Johnson which inhibited the Government from giving out clear guidance to the public in the early days of the pandemic?

Why was it not possible to set in train at an earlier stage the mass production of PPE? Why has the UK struggled to increase its testing capacity? Why was the government so slow in acknowledging the incredibly risky situation in care homes? How much can we trust the official statistics on COVID-19 deaths in the UK?

Were Government Ministers too preoccupied with ‘getting Brexit done’ to dedicate the time and attention necessary in January 2020 as the first warning signs appeared? To what extent, in fact, had preventative measures been run down over the previous two/three years because Brexit preparations were the overriding, even the only, political priority? From the failure to engage with the European procurement scheme to the insistence in ruling out an extension to the Brexit transition phase, there are obvious signs of ideological barriers to the UK government co-operating effectively with European partners.

A worldview based on ‘keeping calm and carrying exceptionally along’ – hard wired into the British establishment, and given sustenance in recent Brexit years – has without doubt impacted significantly upon its mis-handling of COVID-19. It is hard not to conclude that some were not willing, whether they were able or not, to learn lessons in the early stage of the pandemic from elsewhere, and particularly if those lessons were coming from the rest of Europe. For all our sakes, they must start learning now.