Source: The Guardian

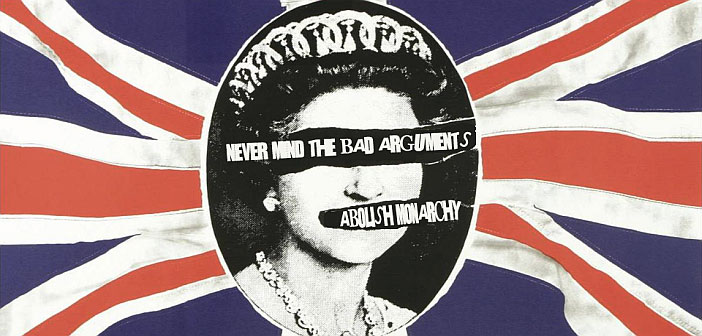

There are other much more powerful obstacles to social advance in Britain than the monarchy, but it remains a festering reactionary drag.

“Monarchy is only the string that ties the robber’s bundle”, wrote Percy Bysche Shelley, the favourite poet of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. This article was written by Seumas Milne in 2013. He is now the Labour Party’s Executive Director of Strategy and Communications.

The last few days have been par for the course. As in the case of every other royal event, the birth of a son to the heir but one to the throne has been reported in tones that wouldn’t be out of place in a one party state. Newsreaders adopt regulation rictus grins. The BBC’s flagship Today programme held a debate to mark the event between two royalists who fell over each other to laud the “stability”, continuity” and “mystery” of the House of Windsor. The press is full of talk of “fairytales” and a “joyful nation”.

But ignoring it leaves a festering anti-democratic dynasticism at the heart of our political system. As things now stand, Britain (along with 15 other former island colonies and white settler states) has now chosen its next three heads of state – or rather, they have been selected by accident of aristocratic birth. The descendants of warlords, robber barons, invaders and German princelings – so long as they aren’t Catholics – have automatic pride of place at the pinnacle of Britain’s constitution.

Far from uniting the country, the monarchy’s role is seen as illegitimate and offensive by millions of its citizens, and entrenches hereditary privilege at the heart of public life. While British governments preach democracy around the world, they preside over an undemocratic system at home with an unelected head of state and an appointed second chamber at the core of it.

Meanwhile celebrity culture and a relentless public relations machine have given a new lease of life to a dysfunctional family institution, as the X Factor meets the pre-modern. But instead of rising above class as a symbol of the nation, as its champions protest, the monarchy embodies social inequality at birth and fosters a phonily apolitical conservatism.

If the royal family were simply the decorative constitutional adornment its supporters claim, punctuating the lives of grateful subjects with pageantry and street parties, its deferential culture and invented traditions might be less corrosive. But contrary to what is routinely insisted, the monarchy retains significant unaccountable powers and influence. In extreme circumstances, they could still be decisive.

Several key crown prerogative powers, exercised by ministers without reference to parliament on behalf of the monarchy, have now been put on a statutory footing. But the monarch retains the right to appoint the prime minister and dissolve parliament. By convention, these powers are only exercised on the advice of government or party leaders. But it’s not impossible to imagine, as constitutional experts concede, such conventions being overridden in a social and political crisis – for instance where parties were fracturing and alternative parliamentary majorities could be formed.

The British establishment are past masters at such constitutional sleights of hand – and the judges, police and armed forces pledge allegiance to the Crown, not parliament. The left-leaning Australian Labor leader Gough Whitlam was infamously sacked by the Queen’s representative, the governor-general, in 1975. Less dramatically the Queen in effect chose Harold Macmillan as prime minister over Rab Butler in the late 1950s – and then Alec Douglas-Home over Butler in 1963.

More significant in current circumstances is the monarchy’s continual covert influence on government, from the Queen’s weekly audiences with the prime minister and Prince Charles’s avowed “meddling” to lesser known arm’s-length interventions.

This month the high court rejected an attempt by the Guardian to force the publication of Charles’s “particularly frank” letters to ministers which they feared would “forfeit his position of political neutrality”. The evidence from the controversy around London’s Chelsea barracks site development to the tax treatment of the Crown and Duchy of Lancaster estates suggests such interventions are often effective.

A striking feature of global politics in recent decades has been the resurgence of the hereditary principle across political systems: from the father and son Bush presidencies in the US and the string of family successions in south Asian parliamentary democracies to the Kim dynasty in North Korea, along with multiple other autocracies.

Some of that is driven by the kind of factors that produced hereditary systems in the first place, such as pressure to reduce conflict over political successions. But it’s also a reflection of the decline of ideological and class politics.

Part of Britain’s dynastic problem is that the English overthrew their monarchy in the 1640s, before the social foundations were in place for a viable republic – and the later constitutional settlement took the sting out of the issue.

But it didn’t solve it, and the legacy is today’s half-baked democracy. You’d never know it from the way the monarchy is treated in British public life, but polling in recent years shows between 20% and 40% think the country would be better off without it, and most still believe it won’t last. That proportion is likely to rise when hapless Charles replaces the present Queen.

There are of course other much more powerful obstacles to social advance in Britain than the monarchy, but it remains a reactionary and anti-democratic drag. Republics have usually emerged from wars or revolutions. But there’s no need for tumbrils, just elections.

It’s not a very radical demand, but an elected head of state is a necessary step to democratise Britain and weaken the grip of deferential conservatism and anti-politics. People could vote for Prince William or Kate Middleton if they wanted and the royals could carry on holding garden parties and travelling around in crowns and gold coaches. The essential change is to end the constitutional role of an unelected dynasty. It might even be the saving of this week’s royal baby.