For the vast worldwide audience that adored him, the laughter Chaplin’s Tramp induced was the antidote to the anxieties and concerns of their lives. And no white feather could poison them against him.

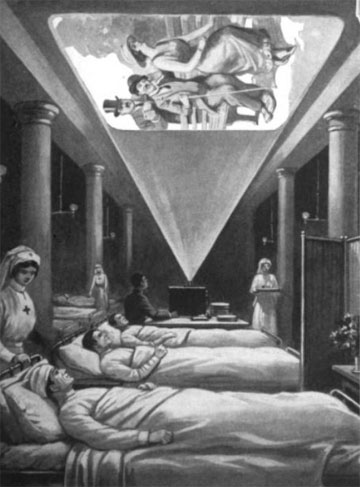

Charlie Chaplin’s world war one satire, Shoulder Arms, was released just weeks before the end of the war in 1918. The film starred Chaplin’s Tramp character who sprung to worldwide popularity within a matter of months of first appearing in 1914. His image was everywhere. Not just on the screen, but also on billboards, comic strips, songs and toys. Chaplin soon became the best-known and most universally loved figure of all time. Crowds clamoured to get admission to cinemas to see “the little Tramp.”Praised as a miracle cure in the first world war, Chaplin’s films were even shown to injured soldiers. Film projectors were specially fitted to project onto the ceilings of field and base hospitals. This way, bedridden soldiers who were unable to sit up could enjoy the films flickering above them.

To boost morale, improvised hospitals near the front line arranged for Chaplin films to be shown for the bedridden, with the ward’s ceiling serving as the silver screen.

Laughing at the Tramp’s gags helped soldiers to forget the physical and emotional trauma they were suffering. In Chaplin’s own words, “Laughter is the tonic, the relief, the surcease for pain.” His silent films crossed language barriers and were widely understood, entertaining a worldwide audience. The laughter he induced was a universal medicine.

While laughter may have helped keep the war wounded alive, British soldiers in the trenches held up cardboard cutouts of Chaplin’s Tramp, hoping the enemy would die laughing. These cutouts finding their way to the front were not unusual, as a letter-writer to the Oamaru Mail wrote in October 1915:

One of the ‘cutouts’ of Charlie Chaplin which are so familiar features outside our cinema theatres has, I understand, now made its appearance in the trenches occupied by a Scottish regiment (says a writer in the Evening Times). The story of how the regiment became possessed of this unusual mascot was told me by the proprietor of a picture palace. The regiment was marching through a seaport town somewhere in the South of England on its way to the front when several members of the battalion noticed the cutout, and decided to have it. Some time later the owner of the establishment was visited by two swarthy Highlanders who begged to be allowed to take the figure of the cinema favorite with them. The proprietor of the house could not resist, and the cutout is now in the trenches, and possibly before now has attracted a few German bullets.

The Tramp was the quintessential everyman, developed from pantomime acts of the English music hall stage. He conveyed a dogged striving for dignity in the face of abject poverty. The ill-fitting bowler hat, little cane, saggy trousers, shrunken dinner jacket, toothbrush moustache, oversized shoes and mannerisms were crafted out of an expertise in making people laugh.

But Chaplin’s laugh-a-minute slapstick was more than entertainment for the troops in the first world war trenches. When the Hollywood icon, a confirmed pacifist, failed to volunteer to fight, he came under fire from the press. The coincidence of his rise in popularity and the onset of war made the little Tramp an easy target for journalists and cartoonists.

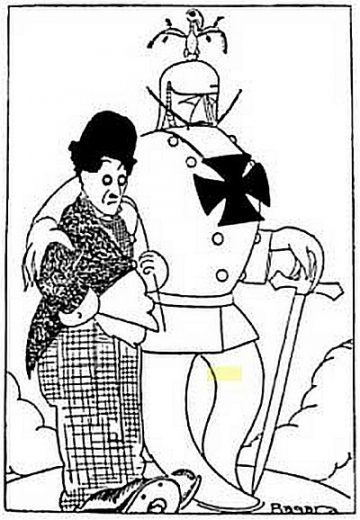

One Spanish cartoon, for instance, had the caption: “the world’s two great comedians,” depicting the Kaiser with one arm around the Tramp’s shoulders. A 1917 French cartoon featured the Tramp wearing a German helmet instead of his usual bowler hat.

The Tramp and the Kaiser. Spanish cartoon, captioned “The world’s two great comedians”

As a British national living and working in Hollywood, Chaplin was dubbed a ‘slacker’ for failing to enlist in either the UK or the US military. After the US entered the war in April 1917, the pressure became intense. He received thousands of white feathers and angry letters aimed at shaming him into enlisting. Years later, in 1932, he would tell the press:

“Patriotism is the greatest insanity the world has ever suffered…Patriotism [in Europe]is rampant everywhere and the result is going to be another war.”

Questions about Chaplin’s failure to fight fed a smear campaign spearheaded by Lord Northcliffe, founder and editor of that vanguard of patriotism, the Daily Mail. In the first world war, Northcliffe served first in the office of propaganda in Asquith’s war cabinet, and then as director of propaganda when Lloyd George became prime minister.

In March 1916, Northcliffe’s Daily Mail attacked Chaplin for the war risks clause in his contract with Mutual Film Corporation. The contract stated simply that for the duration of the war, Chaplin must not return to Britain. The Daily Mail claimed it had received letters in protest of “a man who binds himself not to come home to fight for his native land.”

The British press mogul still kept the pressure on Chaplin. In June 1917, Northcliffe castigated him in an editorial in the Weekly Dispatch (later renamed the Sunday Dispatch) demanding he return at once to Britain to fight:

Charles Chaplin, although slightly built, is very firm on his feet, as is evidenced by his screen acrobatics. The way he is able to mount stairs suggests the alacrity with which he would go over the top when the whistle blew… In any case, it is Charlie’s duty to offer himself as a recruit and thus show himself proud of his British origin. It is his example which will count so very much, rather than the difference to the war that his joining up will make. We shall win without Charlie, but (his millions of admirers will say) we would rather win with him.

The star’s salary was a main bone of contention. Chaplin had invested £25,000 in support of the war, but Northcliffe was unconvinced: “Chaplin can hardly refuse the British Nation both his money and his services.” The Daily Express echoed this, with the headline: “Fighting – for Millions: Charlie Chaplin Still Faces the Deadly Films.”

Northcliffe’s bullying tactics were aggressive, but unsuccessful. With his reputation on the line, Chaplin issued a statement saying he had registered for the US draft and gave a quarter of a million dollars to war activities to the US and Britain. He was, like other Brits living abroad, waiting for word from the British embassy. The British Embassy supported Chaplin’s explanation: “We would not consider Chaplin a slacker unless we received instructions to put the compulsory services law into effect…”

Neither did world war one soldiers consider him a slacker. As Chaplin’s biographer David Robinson describes, the attacks “certainly did not come from servicemen.”

The Daily Mail and Northcliffe’s attacks on Chaplin were out of keeping with the paper’s campaign for supporting British troops. The slacker attacks continued, however, until reports revealed Chaplin had been rejected for the draft for being undersized and underweight. He still received white feathers even years afterwards.

Hoping to end the war sooner, he toured the US hawking war bonds for the US government in April and May 1918. This gave Chaplin his first glimpse of how he could use his star power for politics. By then he had his own studio and the money to do literally what he wanted.

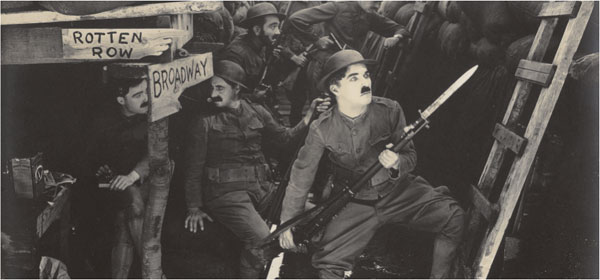

The very next film he started in May 1918 was the antiwar comedy, Shoulder Arms. The film, set mainly in the trenches of the eastern front, begins with the Tramp in boot camp where he is the most awkward rooky in the ‘awkward squad’.

Chaplin in Shoulder Arms, 1918

We see him coping with the mud, the flooding, the fear and the bad food. When he captures thirteen Germans, he proclaims, “I surrounded them.” Ultimately, he disguises himself as a tree trunk in order to cross no man’s land in camouflage. The little Tramp eventually captures the Kaiser.

In his later career, Chaplin became increasingly political and consistently antiwar. “Though he might make comedy from it,” Robinson states, “the folly and tragedy and waste of war were always to bewilder and torment Chaplin.”

Most famously, Chaplin spoke directly against nationalism and militarism in The Great Dictator (1940), a film which critics at the time called pro-communist propaganda because it only mocked Hitler and Mussolini, and not Stalin. He addressed the American Committee for Russian War Relief in San Francisco, in 1942:

I am not a Communist. I am a human being, and I think I know the reactions of human beings. The Communists are no different from anyone else; whether they lose an arm or a leg, they suffer as all of us do, and die as all of us die. And the Communist mother is the same as any other mother. When she receives the tragic news that her sons will not return, she weeps as other mothers weep. I do not have to be a Communist to know that. And at this moment Russian mothers are doing a lot of weeping and their sons a lot of dying…

After the second world war, he suffered further political harassment and denigration. Increasingly critical of class inequalities, his subsequent films, like his 1947 Monsieur Verdoux, exposed him to fresh accusations of communism. Chaplin survived the Red Scare, but the FBI had him under surveillance for forty years. This reached a denouement in 1952 as the US government rescinded his re-entry permit and he exiled himself to Switzerland.

For the soldiers in the first world war trenches and field hospitals, and for the vast worldwide audience that adored him, the laughter Chaplin’s Tramp induced was the antidote to the anxieties and concerns of their lives. And no white feather could poison them against him.

Carrie Giunta is a freelance editor and lecturer in philosophy and/or sound design. Follow her on Twitter @CarrieGiunta

The Great Dictator: Final Speech

I’m sorry, but I don’t want to be an emperor. That’s not my business. I don’t want to rule or conquer anyone. I should like to help everyone – if possible – Jew, Gentile – black man – white. We all want to help one another. Human beings are like that. We want to live by each other’s happiness – not by each other’s misery. We don’t want to hate and despise one another. In this world there is room for everyone. And the good earth is rich and can provide for everyone. The way of life can be free and beautiful, but we have lost the way.