Source: Medium

Venezuela is shaping up to be our Spanish Civil War. And like Spain in the 1930s, the struggle taking place now is of world-historical importance .

If this is to be the end of the Bolivarian Revolution, be in no doubt that it will be a bloody and chaotic affair. For it is no exaggeration to state that Venezuela is shaping up to be our Spanish Civil War. And like Spain in the 1930s, the struggle taking place in the Latin American oil rich country now is of world-historical importance — arguably even more so than those that took place or continue to unfold in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Ukraine, places where rampant and unfettered US-led Western hegemony has left its blood-soaked footprint since the demise of the Soviet Union.

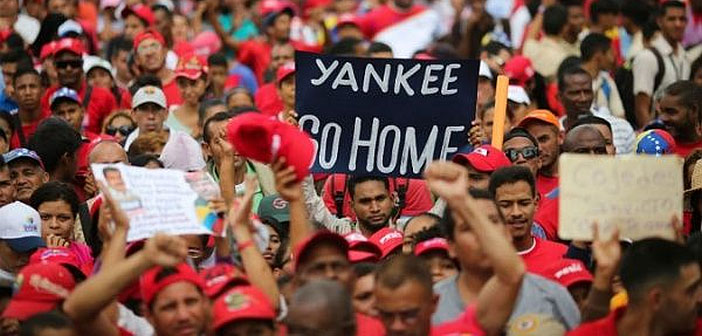

Though some may still retain the capacity to suspend disbelief and elicit the desired Pavlovian response to the rolling out of the Holy Trinity of democracy, human rights and freedom as justification for imperialist aggression by Washington and the usual suspects, there are those of us who refuse to be infantilised. Trump and his neocon grim reaper crew — Bolton, Abrams and Pompeo — are engaged in a campaign against the sovereign government of Venezuela of which Julius Caesar would have been happy to associate himself while rampaging through Gaul, coronating their placeman Guaido in Caracas while salivating over the prospect of getting their gnarled hands on the country’s prodigious oil reserves.

Never knowingly late to the feast, the usual clutch of Washington’s European satellites, with the honourable exception of Italy, have followed instructions in the accustomed manner, joining in the frog’s chorus of recognition of Juan Guaido as interim president and the demand for new elections in a country that sits across the other side of the world in a far off continent. This is at a time when the leader of the opposition in the UK, Jeremy Corbyn, cannot get Theresa May to call an election in the midst of a Brexit crisis that has paralysed her government — a government that continues to mercilessly bludgeon millions of its own people for daring to commit poverty.

Compounding the hypocrisy of perfidious Albion when it comes to Venezuela is the act of grand larceny committed by the Bank of England in sequestering £1.2 billion of Caracas’s gold reserves. At least Dick Turpin went to the trouble of wearing a mask.

In France, meanwhile, Emmanuel Macron has done more for the colour yellow than Dulux could ever dream. Despite harbouring delusions of grandeur as a world leader of note, France’s President of the Rich is has already gone down in history as the most unpopular leader to occupy the Elysee Palace since Louis XVI was striding through the place with his head still attached to his shoulders.

Having lost in Syria, the beast of US hegemony has now turned its attention to Venezuela, whose present troubles are a consequence of capitalism and imperialism not socialism. This is not to claim that President Maduro has not made mistakes or wrong turns since his election as Hugo Chavez’s successor: first in 2013 after the latter’s death, then again in 2018. Both elections, en passant, were adjudged free and fair by international observers; and both were conducted wholly in keeping with the country’s constitution.

But with a nation’s internal development inextricably linked to the external pressures arrayed against it in a given time and space — especially those nations of the Global South whose vulnerability to the hegemonic agenda of the West is ever present—any deficiencies in Maduro’s governance must weighed against the actions of a determined domestic opposition, supported by Washington, and Venezuela’s history of under development.

Oil reserves are both a curse and a blessing for a country like Venezuela. They are a curse in that the economic bounty they provide disincentivises the drive for economic diversification. This has been the case in Venezuela for generations; long periods when the country’s oil was harnessed not in the cause of improving the condition of the masses of the poor and dispossessed, or to invest in other sectors with economic diversification in mind, but to enrich an oligarchy for whom the nation’s poor and dispossessed were invisible.

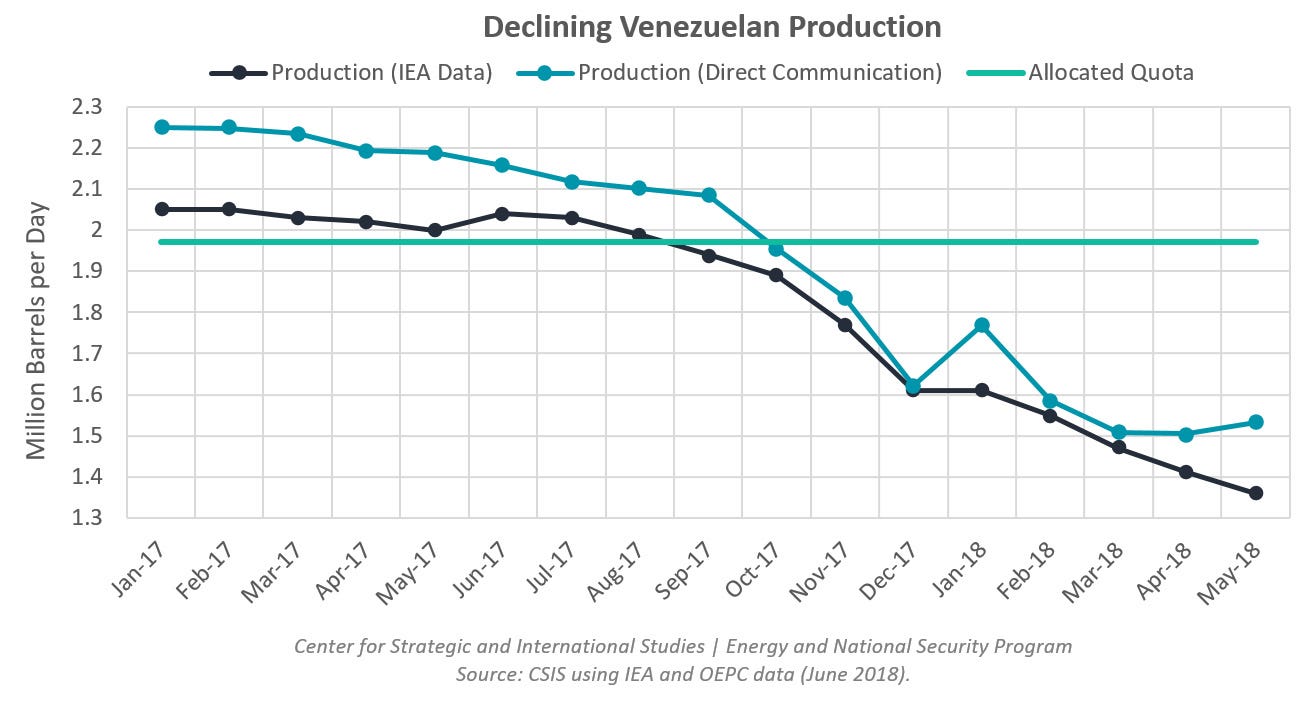

Though oil is a valuable commodity, oil prices can act as a potent weapon, especially when applied to a country that is oil dependent and in the crosshairs of hegemony. Chavez used the revenue from the country’s oil exports when oil prices were buoyant to fund the social programs which transformed the condition of the poor in the barrios. The result was social indicators that inspired millions throughout the region and beyond during his first decade in power. However, with oil accounting for 98 percent of Venezuela’s export earnings, when oil prices took a tumble in 2014, the economy was hit with uncommon severity.

Criticisms of Chavez’s own lack of serious attempt at diversification during the good times are not entirely without foundation, however in a 2016 article in The Nation, Gabriel Hetland points out that that the healthy growth in the Venezuelan economy in the first decade or so of Chavez’s tenure “was made possible by the 2003–2008 oil boom,” but that nonetheless “the non-oil sector grew faster than the oil sector during this period, and government reserves increased.”

What must be borne in mind when it comes to moves towards economic diversification by nations of the Global South is the immovable force of existing market relations. Those relations favour the rich economies of the northern hemisphere in terms of trade, investment, currency and technology. Indeed, in essence, the global economy operates with the express purpose of maintaining a status quo by which the development of the so-called First World is predicated on the underdevelopment of the so-called Third World.

Many analyses have been produced making the case that Chavez damaged Venezuela’s oil industry by extracting too much revenue from it to fund the aforementioned social programs, while not reinvesting enough in what is a capital-intensive industry. Assuming there is some validity to this, the neglect of the poor in the country prior to Chavez was the prime mover in him being elected and re-elected time and again up to his death, and thus their plight was rightly central to his leadership.

Chavez’s showdown with the management and workforce of Venezuela’s state oil company, PDVSA, in 2003 — culminating in his government firing the management and 18,000 workers — did much to disrupt the country’s oil industry, of this there is no doubt. This kind of disruption and sabotage has been a running theme in Venezuela since Chavez came to power (the attempted coup in 2002 being the most obvious example) on the part of an opposition whose actions have consistently demonstrated a preference for ruination and US intervention to socialism in a country it believes is theirs to rule. Because abstracted in the doom-laden analyses on the whys and wherefores behind the destruction of the Venezuelan oil industry and economy, analyses of a type found at Forbes and the FT, is the vicious and unremitting ideological struggle that has underpinned politics in Venezuela during the Chavez and Maduro years.

These one-sided analyses of Venezuela under Chavez and Maduro is no surprise, of course, not when the upsurge in mass consciousness the Bolivarian Revolution produced brought with it the possibility of an escape from a capitalist past that had shackled not only Venezuela but Latin America in its entirety to Washington via the dollar, reducing the entire region to a vast neo-colony.

Where Chavez can be justly criticised is in his failure to root out corruption, and his mismanagement of the nation’s currency in opening the door to the kind of rampant corruption that remains a feature of the country’s woes to this day.

Gabriel Hetland: “The problem stems from the coexistence of three different exchange rates, and the yawning gulf between the lower of two official rates and the black market, or parallel, rate,” creating created “immense incentives for corruption among businesses and state/military officials who are provided dollars by the government at the lower official rate. These businesses and officials often trade these dollars on the black market in order to make obscene profits. Second, the diversion of dollars away from imports and into illegal black-market trading has contributed to severe scarcities as well as the marked drop in imports. Third, production by legitimate businesses (as opposed to ghost enterprises, so-called empresas de maletín) has declined because of their lack of access to dollars and needed inputs.”

Hetland also criticises Chavez’s refusal to lift capital controls at a certain point, though this is problematic given the danger, indeed likelihood, of capital flight in an economy in which the private sector, controlled by the opposition, still retains a commanding footprint.

US and international sanctions, imposed in various guises since 2015, when initially introduced by the Obama administration — along with reguar bouts of social unrest due to the actions of a restive and aggressive opposition — have had the effect of frightening off private investment and restricting access to dollars, thus producing shortages due to the inability of the government to import foods, medicines and other basic necessities.

With the aforesaid factors in mind, Chavez made a sharp turn to Moscow and Beijing before he died. Maduro deepened those ties, borrowing extensively from both in recent years to provide Venezuela with a semblance of a lifeline in the midst of prolonged economic and social crises. Though China’s relations with Maduro have been solely economic, receiving oil in return for loans and investing in the country’s copper and gold mining industries since 2012, Russia has established ever closer geopolitical and military ties. Last December’s non-stop flight to Venezuela from Russia of two strategic bombers and two other long range military aircraft served to highlight those ties.

That Washington views Russia’s growing relationship with Caracas, especially on the level of military cooperation, as a serious threat to its own influence in a region it has always considered a US fiefdom is not in doubt, with the Trump administration’s move for regime change just two months after the aforementioned international flight of Russian military aircraft to the country clear evidence.

Whatever the outcome of the crisis in Venezuela, and at time of writing civil war is a distinct and emerging possibility, the country is now, as with Syria and Ukraine before it, a key frontline in the continuing struggle between the forces of hegemony and unipolarity, led by the US, and those of anti-hegemony and multipolarity, led by Russia and China.

Taking a broader view, when the history of this period in Venezuela’s history is written it will be impossible to avoid exploring the possibility that just as a woman cannot be half pregnant, an economy cannot be half socialist and half capitalist in a time of imperialist hegemony. Authoritarianism is not a charge that can be seriously laid at the door of Hugo Chavez or Nicolas Maduro. On the contrary, it is arguable that both men were not authoritarian enough in relation to a US-supported and funded opposition.

It is also hard to argue that the severe shift to the right that has taken place across Latin America overall, after an all too brief pink tide, has left Caracas isolated with few allies.

“There are decades when nothing happens,” it is said, “and weeks when decades happen.” The crisis in Venezuela confirms that those weeks are upon us.