Source: The National

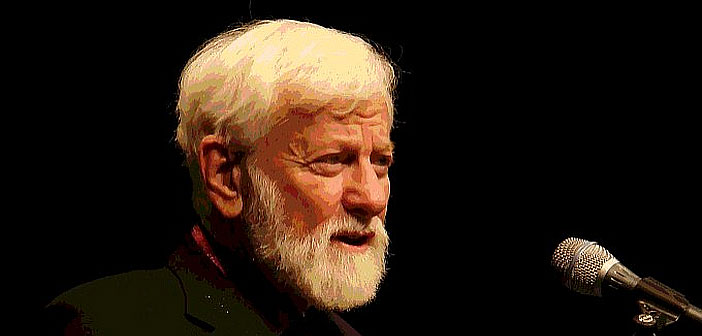

Uri Avnery, a self-confessed former “Jewish terrorist” who went on to become Israel’s best-known peace activist, died in Tel Aviv on 20 August 2018, following a stroke. He was 94.

As one of Israel’s founding generation, Avnery was able to gain the ear of prime ministers, even while he spent decades editing an anti-establishment magazine that was a thorn in their side.

He came to wider attention in 1982 as the first Israeli to meet Yasser Arafat, head of the Palestine Liberation Organisation. At the time, Arafat and the PLO were reviled in Israel and much of the west as terrorists.

Famously, Avnery smuggled himself past the Israeli army’s siege lines around Beirut to reach Arafat. The pair were reported to have maintained close ties until the Palestinian leader’s much speculated upon death in 2004.

Avnery founded Israel’s only significant – if small – peace movement, Gush Shalom, in 1993.

He and his followers tried to build political pressure in Israel and abroad, seeking to convert the lipservice paid to a two-state solution in the Oslo peace process into a concrete Palestinian state.

A harsh critic of Benjamin Netanyahu’s far-right government until the end, Avnery filed his final weekly column two weeks ago, lambasting Israel’s new Nation-State Basic Law as “semi-fascist”.

For Israel’s currently besieged peace bloc, Avnery’s passing is a significant blow.

Despite tributes from Israeli opposition politicians on Monday, his voice had long ago become marginalised at home. He was the last major public figure still visibly fighting to bring about a two-state solution.

His unyielding positions in support of an Oslo-style peace had begun to appear to many on the Israeli right and left as obsolete, especially after Donald Trump’s ascendancy to the White House. Since then, Israel has barely veiled its intention to annex parts of the West Bank, destroying any hope of a Palestinian state.

Avnery publicly rejected a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict based on a shared, single state for Israelis and Palestinians.

He also opposed a general boycott of Israel, as advocated by the growing international BDS movement. Gush Shalom, however, did support boycotts restricted to the settlements.

Avnery arrived in what was then British-ruled Palestine in 1933, aged 10, emigrating with his family from Germany as the Nazis rose to power.

At 15, he was an young recruit to the Irgun, an underground Jewish militia the British classified as a terrorist organisation. But increasingly disenchanted with its attacks on Palestinian civilians, he quit a few years later.

Avnery fought with the Haganah – later to become the Israel Defence Forces – during the 1948 war that founded a Jewish state on the ruins of the Palestinians’ homeland. In later books and articles, he referred to his unit’s role in committing war crimes against Palestinians in the Negev region, in modern Israel’s south.

During the fighting, he was seriously wounded. His dispatches from the battlefront, later compiled as a book, briefly made him a national hero.

But his popularity soon waned. In his memoir, he described his convalescence as a period of dramatic change in his thinking: “The war totally convinced me there is a Palestinian people, and that peace must be forged first and foremost with them.”

It was then, he added, that he became a committed advocate for a Palestinian state.

Through the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, Avnery was best known for publishing his weekly magazine “Haolam Hazeh”, (This World). Its mix of ground-breaking investigations, political muckraking and dissident opinion made him many enemies in the ruling Labour party.

The head of Israel’s domestic intelligence service of the time described Avnery as “Government Enemy No 1”. The magazine’s offices were bombed several times, and Avnery was seriously assaulted. The publication only closed when Avnery started Gush Shalom. The movement on Monday described him as “a far-seeing visionary who pointed to a way which others failed to see”.

Though a dissident figure, Avnery had been popular enough on the left to launch a separate political career, winning seats in Israel’s parliament in the 1965, 1969 and 1977 elections.

When he made a speech in the parliament to relinquish his seat in 1981, he caused an uproar by being the first legislator to wave the Palestinian and Israeli flags alongside each other.

But it was in 1982 that he established a reputation outside Israel. He was smuggled into Beirut to meet Arafat, as Israeli forces encircled the city in an effort to remove the PLO from Lebanon.

It later emerged that Israeli soldiers had been tracking Avnery in a bid to locate Arafat’s hideout and assassinate him. Avnery’s Palestinian escorts managed to elude them.

In his columns, Avnery often credited himself with using the trust he built with Arafat over the next few years to persuade the Palestinian leader to change the PLO’s political direction.

In 1988 Arafat renounced a long-standing Palestinian commitment to a single secular democratic state in historic Palestine, and formally accepted the idea of partitioning the territory into two states.

It was a concession that paved the way to the Oslo accords, signed between Arafat and Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin on the White House lawn in 1993.

That same year Avnery founded Gush Shalom, or “peace bloc”, to build on that momentum as Arafat and the PLO were allowed to return to parts of the occupied territories from which Israel had withdrawn.

As well as believing in the right of Palestinians to freedom, Avnery argued strongly that Israel’s Jewish demographic majority would be under threat unless it separated from the large Palestinian population in the occupied territories.

There were suspicions that some of Arafat’s more misguided assumptions about Israeli society – especially regarding the strength of the peace bloc and the public’s receptivity to the Oslo process – were informed by Avnery.

When the peace process effectively collapsed with the failure of the Camp David summit in 2000 and the eruption of a Palestinian uprising, Avnery again found his message of reconciliation out of favour in Israel.

But in his late seventies, he found a new international audience, as his translated columns were disseminated online.

Avnery hoped through his writings to resurrect what was left of his political legacy. But more often his columns were sought out for the light he could shed on current controversies, drawing on insights gained from his knowledge of historical episodes now largely overlooked.

At the height of the second intifada, Avnery and Gush Shalom were often alongside Palestinians protesting against abuses by the Israeli military or the settlers. They also demonstrated to stop Israel’s building of a “separation barrier” that subsequently ate up large chunks of Palestinian land in the West Bank.

In 2003, Avnery joined Arafat in his besieged presidential compound in Ramallah, serving as a “human shield” – to foil an expected Israeli assassination attempt. After Arafat died in mysterious circumstances a year later, Avnery was among those arguing that Israel was behind his poisoning.

His last column explored one of his enduring concerns: Israel’s identity as a Jewish state. It was provoked by the recent passage of the Nation-State Basic Law, which confers on Jews around the world privileges in Israel that are denied to the country’s large minority of Palestinian citizens.

For many years Avnery had been among those warning that Israel could not be a democracy if it did not treat all citizens as equal, but instead allocated key rights based on differing Jewish and Arab nationalities.

In 2013 he and other Israelis appealed to the supreme court to recognise for the first time an Israeli nationality shared by all citizens. The judges rejected their arguments.