“The artist must take sides,” said Robeson. “He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice.”

Source: The Guardian

These are strange times for popular music and politics. On the one hand, the opposition to Donald Trump now extends so deeply into the entertainment industry that the president struggled to find any real talent willing to play his inauguration.On the other hand, it’s by no means clear what difference most anti-Trump interventions by musicians actually make. After all, during the election, the galaxy of A-listers backing Hillary Clinton spectacularly failed to generate either turnout or votes, with some pundits even suggesting the campaign’s reliance on celebrity power legitimised Trump’s claim to fighting “liberal elites”.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the power of music and the uses of fame over the last few years, as I’ve worked on my book No Way But This: In Search of Paul Robeson.

Robeson’s name might not mean much to some younger readers. Yet as recently as 1964 a journalist could describe him, fairly uncontroversially, as “the best-known American in the world”.

The son of an escaped slave, Paul Robeson graduated Phi Beta Kappa on a scholarship from Rutgers before studying law at Columbia university. He was arguably the greatest footballer of his generation (some say of all time); he played basketball professionally and was seriously tipped as a heavyweight contender to fight Jack Dempsey. He was handsome and impossibly charismatic, spellbinding, prize-winning orator, who could sing in over 20 languages, including Russian, Chinese, Yiddish and a number of African tongues.

The son of an escaped slave, Paul Robeson graduated Phi Beta Kappa on a scholarship from Rutgers before studying law at Columbia university. He was arguably the greatest footballer of his generation (some say of all time); he played basketball professionally and was seriously tipped as a heavyweight contender to fight Jack Dempsey. He was handsome and impossibly charismatic, spellbinding, prize-winning orator, who could sing in over 20 languages, including Russian, Chinese, Yiddish and a number of African tongues.

Robeson launched his vocal career in the mid-1920s with reinterpretations of spirituals, the “sorrow songs” of the American plantations. The spirituals expressed the misery of slavery through biblical themes but their innate ambiguity also allowed Robeson to voice the preoccupations of the Harlem Renaissance.

For instance, Go Down, Moses celebrated the release of the Israelites from bondage. But when Robeson sang “let my people go”, his audience understood the challenge to all present-day pharaohs.

Likewise, the exquisite Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child emerged out of the familial separations of slavery. Robeson’s rendition, however, also spoke to the experience of the Great Migration, the process in which African Americans left their homes to flee north for jobs and an escape from racist violence.

Robeson’s critical and popular triumph not only reshaped Shakespearean theatre, it also struck a blow against the assumptions underpinning Jim Crow America.

Though Robeson became a huge Hollywood star (in films such as Show Boat, Sanders of the River, The Proud Valley and so on), he consistently struggled to find parts worthy of his talents.

As a musician, he enjoyed more freedom. Critics urged him to embrace a traditional operatic or classical repertoire, but his deepening political commitments led him to identify as a folk singer, assiduously learning languages to perform the songs of different cultures in their original form.

“The artist must take sides,” he announced. “He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”

That declaration was made in the context of the Spanish civil war, a conflict that Robeson, like many others, recognised as the last opportunity to prevent the advance of fascism. He travelled to the Spanish front line in support of the International Brigades, a multiracial, anti-fascist army based on volunteers drawn from almost every country in the world.

In besieged Madrid, the desperate Republicans quite literally deployed Robeson’s music as a weapon, rigging up loudspeakers so that his bass baritone carried to the fascist trenches.

But it was probably in America in the 1940s that Robeson used his celebrity most effectively, in a prolonged campaign against segregation that predated the more famous boycotts of the civil rights era.

For instance, in a concert in Kansas City, Robeson stopped singing when he realised that, contrary to what he’d been promised, his audience was divided along racial lines. When the booking agent apologized, the victory spurred a broader campaign against discrimination in the state. As the historian Gerald Horne says, “Robeson was a kind of Pied Piper of anti-Jim Crow, journeying from city to city inspiring fellow crusaders.”

In the 1930s, Robeson had visited Moscow and the apparent absence of anti-black feeling amazed him. For the rest of his life, he remained an enthusiastic supporter of the Soviet dictatorship, backing the regime even as news of Stalinist atrocities spread.

Not surprisingly, during the cold war, red baiters in the US increasingly targeted him.

By 1952, Robeson had become, in Pete Seeger’s words, “the most blacklisted performer in America”. The FBI intimidated promoters to deny him venues while radio stations refused to play his records, which were no longer available in the shops. He couldn’t sing at a commercial hall, no producer would put him on stage, and his movie career had long since come to an end. Worse still, the state department denied him a passport, trapping him inside the US.

The destruction of Robeson’s reputation dates from that period, a time when attending a Robeson concert became a suspicious act and sporting records were surreptitiously revised to disguise his past achievements.

Many other figures smeared during McCarthyism – Albert Einstein, Langston Hughes, Charlie Chaplin, WEB Du Bois, etc – have been subsequently rehabilitated. Robeson’s ongoing obscurity stems from his obstinate refusal to recant or back down.

“I am a radical,” he insisted, “and I am going to stay one until my people get free to walk the Earth.”

Called before the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956, he was asked why, given his beliefs, he remained in the United States. “Because my father was a slave,” he replied. “And my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear”’

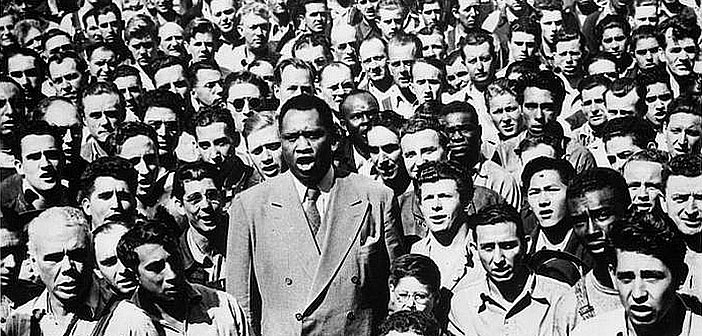

When he won his passport back in 1958, he embarked on a worldwide tour. You can glimpse something of Robeson’s effectiveness as a political singer in the film that survives from his visit to Australia.

Famously, Robeson gave the first ever recital at the Sydney Opera House – a concert delivered to the trade unionists constructing the building. In that performance, Robeson sang Ol’ Man River, his best-known track. The song – from the musical Show Boat – was composed with Robeson in mind by Oscar Hammerstein and Jerome Kern, as a conscious imitation of the spirituals. Robeson initially thought the role of Joe in Show Boat to be demeaning – before changing his mind and then utterly dominating both the stage show and the subsequent movie.

In their original form, the lyrics spoke of phlegmatic African American resignation to misery and oppression.

Ah gits weary

An’ sick of tryin’

Ah’m tired of livin’

An’ skeered of dyin’,

But ol’ man river,

He jes’ keeps rolling’ along.

In Sydney, Robeson sang instead:

But I keeps laffin’

Instead of cryin’

I must keep fightin’

Until I’m dyin’

When he mouthed the word “laffin’’’, his lip curled in scorn; at “fightin’”, he punched his fist in the air, making clear to the listening unionists that he had in mind their shared enemies: the employers and politicians for whom an uneducated labourer in Sydney was no better than a black man in Tennessee.

The song now suggested that what was inescapable was not resignation but human dignity – the desire for freedom that persisted, and would prevail, like the mighty river itself.

In 1960, construction workers were not respectable. Concert halls did not cater to labourers, whom few considered deserving of fine music or sophisticated entertainments.

So, with the gesture at Bennelong Point, by transforming – if only for a lunch hour – their worksite into the musical venue it would eventually become, Robeson made a statement characteristic of his life and career.

You aren’t, he said to them, simply tools for others; you’re not beasts, suitable only for hoisting and carrying, even if that’s the role you’ve been allotted. You’re entitled to culture, to music and art and all of life’s good things – and one day you shall have them.

According to some accounts, by the end of the performance, men in the crowd were silently weeping.

What made Robeson’s interventions so powerful? First, and most obviously, he was an extraordinarily gifted artist, over and above his politics. When the critic Peter Deier described Robeson as “the most talented person of the 20th century”, he wasn’t exaggerating.

Second, though Robeson had no compunction about using his fame, he was committed to a politics of social change from below. He didn’t simply urge his fans to donate to a charity or check their personal privilege. On the contrary, he assured them that they themselves had power – and they should use it.

Thus, in 1938, he explained to a journalist how ordinary people mattered more than stars:

During one of my films I was struck by this very forcibly. There was everybody on the set, lights burning, director waiting, head of the company had just come on to the set with some big financial backer to see how things were going – and what happened? Everything stopped. Why? Because the electricians had decided it was time to go and eat, they just put out the lights and went and ate. That’s my moral to your readers.

Third, Robeson persistently sought to connect disparate issues and link varied oppressions, in a manner that’s rare today. For instance, his film The Proud Valley is based on a comparison that Robeson often made between Welsh mining towns and African American communities.

Likewise, on his Sydney trip, he insisted on meeting with Indigenous activists – and then, in his public appearances (such as in the clip below), raised Australia’s brutal history in the context of the anti-colonial struggles taking place everywhere at that time.

Fourth, when Robeson urged his audience to become active, he could often direct them to groups and campaigns through which that activism might be made meaningful. The Opera House concert, for instance, was arranged by trade unionists – and, as a result, Robeson’s performance gave a direct spur to workplace organisation.

That’s an obvious difference between Robeson’s era and the context in which artists are speaking out against Trump in 2017.

In the United States, as in Australia, the trade unions and the radical movements to which Robeson oriented during the latter half of his career have either declined or disappeared, leaving something of an organisational void for grassroots activism.

Under those circumstances, it’s easy for musicians and other celebrities to see themselves as the sole agents for change – and then engage in the sort of self-congratulatory posturing that helps Trump more than it hurts him.

At the same time, significant campaigns do exist, and they’ve been given new impetus by Trump’s victory. The Black Lives Matter movement, in particular, was both reflected in, and reinforced by, hip-hop music in particular – and it’s not surprising that rappers have so far produced some of the best musical responses to the Trump presidency.

As many people have noted, in 2017, we’re entering uncharted political waters. But that doesn’t mean we can’t draw on the resources of the past. As the cultural resistance grows, it’s worth looking back on the giant legacy of Paul Robeson.

No Way But This: In Search of Paul Robeson by Jeff Sparrow is published in Australia by Scribe