Whatever government is formed in the UK after the 12 December election, it faces an immense challenge. The British economy is in a mess and its society is riven with division.

After ten years of austerity measures under Conservative/Liberal Democrat governments, public services and welfare benefits have been cut to the bone and beneath. The British state pension is the lowest in Europe! The NHS, after being hollowed out by outsourcing and internal privatisation and then starved of funds, is on its knees. Social care for the old and infirm has been decimated and/or hideously expensive. School classroom sizes are higher than ever, higher education colleges are going bust and students are racking up huge debts. The housing shortage is so bad that young people are forced to live at home with parents or in crowded, unfit private rental accommodation. Transport is an expensive nightmare: rail, energy and fuel prices are the among the highest in Europe.

Inequality of wealth and incomes are as high as in the 1930s. While Britain boasts of 135 billionaires, 14 million are officially classed as poor and 4 million children are living in poverty. Regional disparities in living standards between London and the south east and the rest of the UK are the widest in northern Europe. Millions work in the poorly paid self-employed ‘gig’ economy, and one million people work on zero-hours contracts often for wages below the official minimum wage; while the disabled and ill are forced back into low wage work through the removal of benefits.

All this while people of Britain are divided over whether it is better to leave the European Union or not; whether Scotland and Northern Ireland should break with the Union; and whether immigration is good or bad for the economy and society.

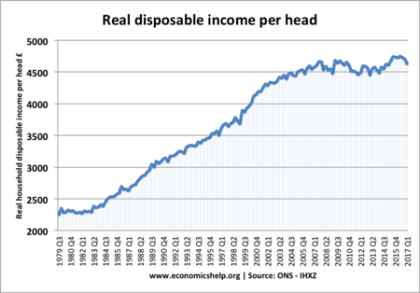

Most important, on the economic front, Britain’s growth of national output is slowing as the population expands, making it increasingly difficult to provide the resources to meet these challenges. Britain’s economic growth is disappearing fast. The capitalist sector of the British economy has failed to deliver for the needs of people, although it has delivered higher profits and house prices and a booming stock market for the rich. Real disposable income per head has more or less stagnated since the end of the Great Recession, the longest period in 167 years!

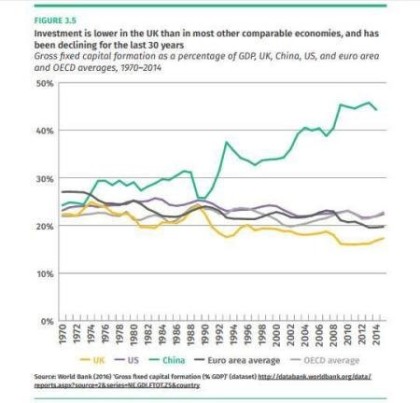

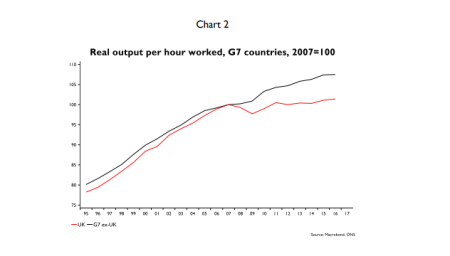

That is because investment by big business is contracting, partly because of the uncertainty of what will happen after Brexit and partly because both domestic and foreign investors no longer expect much of a return from investment in Britain. With falling investment comes low growth in what each worker in Britain can produce. And low productivity growth means permanent low economic growth.

Real output per hour worked rose just 1.4% between 2007 and 2016. Within the G7, only Italy performed worse (-1.7%). Excluding the UK, the G7 countries have experienced a 7.5% productivity increase over this period, led by the US, Canada and Japan. In addition, the ‘productivity gap’ for the UK – the difference between output per hour in 2016 and its pre-crisis trend – is minus 15.8%; while the productivity gap for the G7 ex-UK countries is minus 8.8%.

British capitalism is a ‘rentier economy’, concentrated on finance, property and business services, more than any other major economy. Having helped trigger the global financial crash and the huge slump in 2008-9, the City of London has done nothing since to support UK businesses, particularly smaller ones. Loans to smaller companies have fallen. Instead, bank loans have poured into real estate. Britain’s productive sectors (manufacturing, professional scientific & technical activities, information & communication and administrative & support services) account for 28.7% of real GDP. But bank loans to these four sectors total just 5.5% of GDP. This is less than the total of loans outstanding to companies engaged in the buying, selling & renting of real estate (6.9% of GDP).

So what is to be done? The UK Labour party’s election manifesto takes on the challenge. The key underlying issue on which all depends is finding a way to increase investment in more productivity-enhancing projects and in a better trained and skilled workforce, employed in decent conditions and paid living wages. In this regard, Labour is making serious attempts to reverse British industry’s decline.

First, it looks to launch a Green New Deal which will direct resources away from unproductive activities and instead focus on curbing the acceleration in global warming by investing in renewable energy projects and offering hundreds of thousands of apprenticeships for skilled jobs in green projects.

Second, it looks to bring back into public ownership the key energy and water companies, ending the rip-off of the public by the current private monopolies. Rail and bus transport will also return to the public sector, thus ending the wasteful anarchy of franchised routes and inefficient and expensive local bus services. And Labour will aim to deliver free super-fast broadband internet to every household within ten years, at half the cost that the private sector would spend, by taking over the broadband division of BT. And it would bring the Royal Mail back into public ownership. The largest companies would be expected to give their workers shares in the company with rights to representation on company boards. And collective bargaining rights would be restored, reversing Thatcher’s anti-trade union laws. These measures would provide new impetus for investment and jobs.

And third, Labour would expand public investment to compensate for the failure of businesses to invest. Labour would set up a Strategic Investment Board to coordinate R&D, commercial services and information flows. It would set up a state investment bank to invest £25bn year in projects and infrastructure. It would start a new banking service for small businesses based on the Post Office.

How will all this be paid for? Well, under the existing conditions, Labour plans to raise income taxes for the highest 5% of earners (ie more than £80,000 a year); and it aims to capture missing taxes currently unpaid by big business and the rich through tax havens and evasion – that is estimated at $25bn a year! Labour would be prepared to increase government borrowing to fund more spending on health, education and some of the longer-term projects. Given that interest rates are at their lowest in 60 years, the cost of borrowing would add little to annual budget costs. Also planned investments should deliver increased productivity and growth and thus more tax revenues. It is estimated that the cost of nationalising energy, rail, water and telecoms would be covered from the revenues of these sectors within seven years.

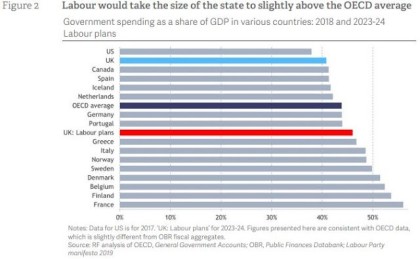

Contrary to the media reaction, this would not make the UK have the biggest state spending of major economies. As the Resolution Foundation shows, it would take the size of government expenditure as a share of total annual spending to around 45% of GDP, in the middle of the range within OECD economies.

As Simon Wren-Lewis says, in his comprehensive post, “another way of putting it is that the UK will become closer to the European average, and further away from the US/Canada level.”

Can this plan work to turn Britain into a more prosperous, more equal and more united society? Much depends on three things. First, can just one state bank and investment board really be enough to re-direct Britain’s rentier economy into more productive areas for employment? Labour does not propose to bring into public ownership and control the big five banks or the major insurance companies and pension funds. Yet these will continue to provide the bulk of potential investment funding (some 15% of GDP compared to the state’s 4%, at best). That will weaken the ability of a Labour government to deliver real improvements in investment, services and incomes. Labour’s tax and other measures to redistribute income and wealth from the super-rich to the rest are also very limited. Indeed, although Labour plans to raise the annual increase on spending on the NHS by 4% a year, that is still less than under the Blair government and is barely enough to meet the needs of an ageing population. And Labour’s measures will only make a small dent in the extreme levels of inequality.

Second, there is the inevitable reaction from big business and the media. They will go hell for leather to block and reverse Labour plans and any sign of failure will be seized upon. And so there is a serious risk that Labour’s relatively modest plans to rebalance the wealth and power within the country may falter. Big business and the rich have already threatened to take their investment and money elsewhere and the coming to power of a radical Labour government may well provoke what is called ‘capital flight’, inducing a run on the value of the pound and driving up interest rates. Labour may have to take more drastic measures like capital controls. But without control of the major banks, the currency would be under threat from this financial terrorism.

And third, and most important, is the high likelihood of a new global slump in production, investment and employment. It has been ten years since the end of the Great Recession, the biggest global slump since the 1930s. Another recession is well overdue and there are signs that is coming, as the major economies are slowing down significantly and the trade and technology war between the US and China is intensifying, destroying world trade growth. By this time next year, the new British government could be faced with British businesses going bust, laying off workers and imposing an investment strike.

The only way the impact of such a recession could be reduced would be for Labour to take control of what used to be called the ‘commanding heights of the economy’: the banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and the key strategic companies in Britain’s main manufacturing, energy and other productive sectors. Only then could a national plan for investment and jobs and to combat climate change be possible because it would not rely on capitalist investment. Labour’s current economic policies fall short of that. Instead, Labour’s leaders and advisers rule out such drastic measures because they think they will not be necessary and instead ‘a regulated and managed capitalism’ can still deliver the needs of British people. History tells us otherwise.

This was first published on The Next Recession