In his 1928 musical play, The Threepenny Opera, Bertolt Brecht regales us with the following critique of the dehumanising properties of capitalism. ‘’A man who sees another man on the street corner with only a stump for an arm will be so shocked the first time he’ll give him sixpence. But the second time it’ll only be a threepenny bit. And if he sees him a third time, he’ll have him cold-bloodedly handed over to the police.’’

How many of us reading those words could honestly claim immunity from the kind of desensitisation Brecht describes? Unless you are living on an island in the middle of nowhere, it is almost impossible not to be found guilty of it on a regular basis. How else could we cope with the ubiquity of suffering and despair we encounter as we go about our daily lives — the army of homeless people begging for change, the human casualties we see all around us (or perhaps refuse to see) of a brutal system underpinned not by justice or fairness or solidarity but by social Darwinism?

In the wake of the 2008 economic crash and the resulting imposition of austerity — an ideologically-driven project to transfer wealth from the poor and working class to the wealthy and business class in order to maintain the rate of profit — the callous and cruel disregard for the most vulnerable in society spiked to the point where it became de rigeur to desensitise ourselves to the plight of its victims: the unemployed, benefit claimants, the low waged, and so-called underclass.

In other words, those whose ability to survive was dependent on the state, on an already truncated social wage, were lined up by the Tories and right wing press as sacrifical lambs in service to a strategy of deflection from the underlying cause of the economic crash — namely private greed and an unregulated financial and banking sector. Instead, the crisis caused by said private greed was successfully turned into a crisis of public spending, nicely setting up the poor, vulnerable, and most powerless demographics in the country as convenient scapegoats.

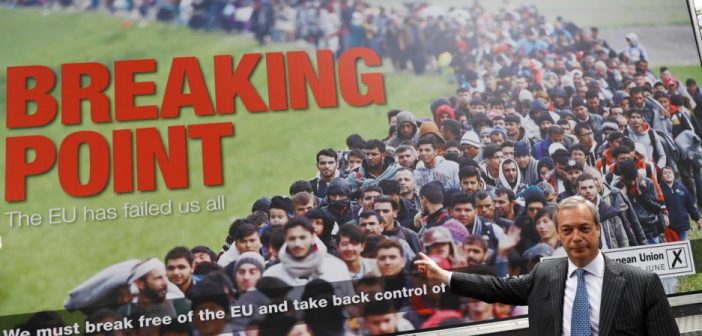

This scapegoating has continued apace; only now, on the back of the EU referendum, the guns have been turned on migrants, on foreigners, refugees, and by extension existing minority communities, depicted as the fount of all evil — a threat to that hoary old leitmotif, constantly being drummed into us, of British values.

In parenthesis, what precisely are these British values that we’re supposed to hold so dear? Are we talking an empire that plumbed new depths of racism and brutality in its super-exploitation of millions of human beings and their lands? Are we talking the propensity for unleashing regime change wars that have wrought chaos and carnage on a mammoth scale?

Or are we talking the history of callous cruelty when it comes to the disregard for the plight of the poor that has long been the shameful hallmark of a sociopathic ruling class? Or how about the shining contribution to the cause of democracy represented by an unelected head of state, the monarchy, and likewise an unelected second chamber, the House of Lords?

Brexit is the culmination of this callous process of scapegoating and ‘othering’, fuelled by the mounting despair and, with it, righteous anger of those who have and continue to suffer at the hands of a government for whom cruelty is a virtue and compassion a vice.

The problem is that this anger has been channelled at the wrong target, signifying the extent to which the right is winning, if indeed it has not already won, the battle of ideas. That a section of the left has succumbed to right wing nostrums on the EU, free movement, and migrants as the cause of society’s ills in our time, rather than the government’s vicious austerity, obscene inequality, and the continuing unfettered greed of the private sector, merely confirms it.

In the wake of Brexit, we have witnessed an opportunistic attempt by the Brexit-supporting left to justify its capitulation to these right wing nostrums as the rejection of a liberal fixation on identity politics to the deteriment of class. In other words we are meant to believe that right is the new left.

That the traditional organised industrial working class no longer exists, this is a symptom of the defeats suffered at the hands of Thatcher in the 1980s, when she unleashed class war as part of the structural free market adjustment of the UK economy. The result was the country’s wholesale deindustrialisation and the atomisation of working class communities. Collectivism was replaced by individualism and a homogenous class identity with a heterogenous cultural one.

Thus identity politics, which undoubtedly do exist to the detriment of class, filled the vacuum left behind, providing the locus of political activity for hitherto marginalised groups. However this in no way implies that Brexit, or indeed Trump, represents a return to the politics of class.

The campaign to exit the EU was not led by Che Guevara or Rosa Luxemburg. On the contrary, it was led is today is being driven by a clutch of ultra right-wing ideologues for whom the left-behind and put-upon Brexit-supporting working class filled the role of ideological fodder, whom the former managed to win to the xenophobic, nativistic and reactionary precepts of British nationalism.

Three years on, the result is the looming prospect of shortages of medicines, the disruption of supply chains, chaos at the ports, and a return to conflict in Ireland.

But of course none of that matters to the feckless doctrinaires who make up the ranks of the pro-Brexit left. Tony Benn was anti-Europe and so that’s the end of the argument. It marks the difference between tailoring your analysis and position to actual events, and attaching same to those events.

To paraphrase someone who understood the importance of keeping to the former and never lapsing into the latter, “Left wing Brexitism is an infantile disorder.”