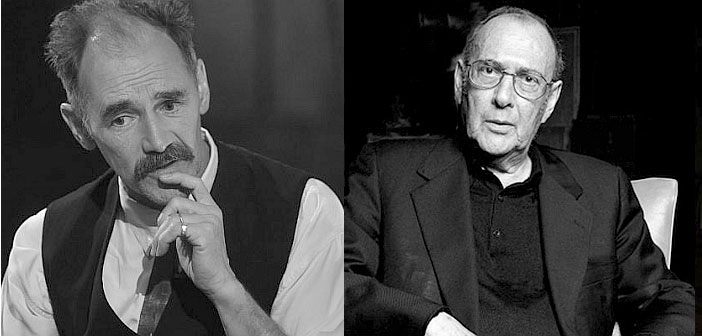

One of the all-time greatest actors speaking the provocative and profound words of one of the all-time greatest playwrights and political agitators.

The Pinter Theatre was packed to the rafters on 2 October 2018 in high anticipation of a major event. We were there to witness a very special occasion: a performance by Mark Rylance of Harold Pinter’s 2005 acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he titled Art, Truth and Politics.Sir Mark Rylance is recognized as one of today’s finest actors, both in theatre and film. In 2016 he won the Oscar for best supporting actor in the film Bridge of Spies.

Harold Pinter was also a fine actor, but is best known as one of the most important writers of the 20th century, not least for his hugely influential plays.

The performance was part of a season of Pinter plays, which runs to February 2019, in celebration of Pinter’s literary legacy and to commemorate the tenth anniversary of his passing. Artistic Director for the season, Jamie Lloyd, said: “This is sure to be a powerful evening; one of the all-time greatest actors speaking the provocative and profound words of one of the all-time greatest playwrights and political agitators. The Nobel Lecture concerns the quest for truth in art and the scarcity of truth in politics. These performances couldn’t be more timely.”

And how right he was.

As well as in their professional lives, Mark Rylance and Harold Pinter were linked by their political activism, particularly in their opposition to injustice and war. Unsurprisingly, this led both to a close involvement with the Stop the War movement (STW), which was founded nearly two decades ago in response to the war in Afghanistan, and is one of the most significant mass movements in British history.

Pinter was a regular contributor to Stop the War events, speaking on demonstrations at which he often read a poem he had written especially for the occasion.

Mark Rylance says the STW demonstration on 15 February 2003, when two million came onto London’s streets in protest against the Iraq war, was “one of the most profound moments of my life”. Rylance is today a STW patron, regularly appearing at its events. His two performaces of Pinter’s Nobel lecture were also fundraising events for Stop the War.

Harold Pinter was seriously ill in 2005 with advanced cancer and other health issues, so was unable to travel to Norway to make his acceptance speech in person, delivering it instead on film from his wheelchair. It was – despite Pinter’s obvious physical discomfort and his seriously weakened voice – an electric performance, in which his anger at the injustices of the world were given powerful expression, in a speech which stands in its importance as one of the great radical speeches since the end of World War Two.

Mark Rylance’s performance brilliantly caught the rhythms and intonation of Pinter’s own voice, and the intensity of his outrage over the momentous crimes against humanity that went unrestrained and unpunished – particularly those committed in the name of US foreign policy.

He moved purposefully round the stage, savouring every sentence of Pinter’s text, the theme of which centred on truth, and how it is portrayed both in literature and in the world generally. Pinter opened his speech with this statement:

In 1958 I wrote the following: ‘There are no hard distinctions between what is real and what is unreal, nor between what is true and what is false. A thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false.’

I believe that these assertions still make sense and do still apply to the exploration of reality through art. So as a writer I stand by them but as a citizen I cannot. As a citizen I must ask: What is true? What is false?

Truth is forever elusive in drama, says Pinter. But truth is also elusive in political language, due to how it is filtered through the media, and because

… the majority of politicians, on the evidence available to us, are interested not in truth but in power and in the maintenance of that power. To maintain that power it is essential that people remain in ignorance, that they live in ignorance of the truth, even the truth of their own lives. What surrounds us therefore is a vast tapestry of lies, upon which we feed.

Behind this “vast tapestry of lies”, says Pinter, lies a reality in which “the United States supported and in many cases engendered every right wing military dictatorship in the world after the end of the Second World War”, from Nicaragua to Greece, from Indonesia to Chile.

This is in addition to US wars in Korea and Vietnam and – in Pinter’s final years – Afghanistan and Iraq, which, he says, “was a bandit act, an act of blatant state terrorism, demonstrating absolute contempt for the concept of international law”. Pointing his finger at George W Bush and Tony Blair, Pinter asks, “How many people do you have to kill before you qualify to be described as a mass murderer and a war criminal? One hundred thousand? More than enough, I would have thought.”

And since Pinter’s death, we have had the invasion of Libya, the catastrophic subversion by the US and its allies in Syria and countless other interventions.

Was all this mass slaughter and destruction attributable to American foreign policy? asks Pinter. “The answer is yes,” he says. “But you wouldn’t know it”. Adding in a now much quoted passage:

It never happened. Nothing ever happened. Even while it was happening it wasn’t happening. It didn’t matter. It was of no interest. The crimes of the United States have been systematic, constant, vicious, remorseless, but very few people have actually talked about them. You have to hand it to America. It has exercised a quite clinical manipulation of power worldwide while masquerading as a force for universal good. It’s a brilliant, even witty, highly successful act of hypnosis.

This was a theme taken up by the audience in the Q&A which followed the performance, in which Mark Rylance was joined by two founder members of Stop the War, Lindsey German and Chris Nineham.

One of the first quesions raised from the audience was whether the root cause of endless war we experience today was the result of human nature, rather than a consequence of US foreign policy, as Pinter argues. To which Chris Nineham replied that people are not ‘naturally’ predisposed to be aggressive and uncaring; look at people’s daily lives and we see that it is collaboration and unselfishness which are the main characteristics. Lindsey German added that how people act depends on the social context in which they live: there are many examples of societies in which war and conflict are not the predominant values, as they are today, particularly in the world as dominated by US imperialism.

The musician Dave Randall asked about Jeremy Corbyn, who has inspired a movement for justice and peace which grew directly out of the anti-war movement. Corbyn was for many years the chair of Stop the War before his leadership transformed the Labour Party into the biggest political party in Europe. How could he be supported?

Mark Rylance replied that it is in collective action that we can best support a politician like Corbyn. But Harold Pinter had also given an answer to this question in his summing up at the end of his Nobel speech:

I believe that despite the enormous odds which exist, unflinching, unswerving, fierce intellectual determination, as citizens, to define the real truth of our lives and our societies is a crucial obligation which devolves upon us all. It is in fact mandatory.

The final question from the audience asked the panel why we are so powerless when there are so many of us, and why is it that those in power, who are so few in number, are not scared of the vast majority.

To which another audience member replied: But they are scared, which is why they do everything they can to vilify and smear someone like Jeremy Corbyn, who has inspired a mass movement committed to the causes of peace and social justice, and looks like he is on the brink of forming a government based on those values.

It is a reply that Harold Pinter would have welcomed.

This was a very special evening to be long treasured by all who were there, and it is hard to imagine another actor who could have captured both the spirit and meaning of Pinter’s words with the clarity and emotional force that Mark Rylance gave to them.