Through his music and life, Mikis Theodorakis, the incomparable composer, everlasting fighter, partisan, communist and activist brought new meaning to freedom and political awareness. Theodorakis remains a symbol of the fight for freedom, democracy and social justice as well as a vibrant reminder of the battle against oppression and despair, as well as resistance.

The first time Theodorakis was imprisoned and tortured for his ideals he was only 18 years old, as a resistance fighter who served in the Greek People’s Liberation Army ELAS in the German occupation of Greece. During Greece’s bloody civil war, he was deported multiple times for his communist profile and sent to the camp island of Makronisos. After his release he went to Paris where he studied music and produced his first compositions, earning international appraise. Against the political circumstances, he returned to Greece in 1960, where he was tortured and detained again by the military junta that prohibited his music, which was always deeply political. After his friend Grigoris Lambrakis, a left-wing politician, was slain during a peace march in 1963, Theodorakis entered politics. In 1968, he was taken to a prison camp. Despite his confinement, Theodorakis was able to smuggle out cassette recordings and sheet music.

In 1970, Theodorakis moved to Paris. He met Pablo Neruda and Salvador Allende in 1972. After the September 1973 coup against Allende, Theodorakis’ setting of the “Canto General” became a hymn of the Chilean resistance. He returned to Greece as a hero and a political giant after the dictatorship toppled in 1974. He was a delegate for the newly legalized Communist Party and remained politically active throughout his whole life, joining protests against austerity in the 2010s and contradicting the neo-fascist “Golden Dawn”.

On behalf of the Party of the European Left, we extend our deepest condolences to his comrades, friends and family.

]]>The festival line up included internationally known performers who oppose racism and discrimination such as Gogol Bordello, Skunk Anansie, Ziggy Marley, and Prophets of Rage. The last band includes former members of Rage Against The Machine, Audioslave, Public Enemy and Cypress Hill.

The festival stand of the ‘NEVER AGAIN’ Association was the venue of a debate with Nay San Lwin, a human rights activist and representative of the persecuted minority of Rohingya in Myanmar (Burma). For years he has been drawing the attention of world public opinion to the genocidal practices used by the military dictatorship against the Rohingya, such as violence, hunger and forced evictions. The genocide in Myanmar has been documented by the United Nations. The other participants of the debates organized by ‘NEVER AGAIN’ included members of Opferperspektive (Victim’s Perspective), a German organization which helps the victims of hate crimes, as well as activists from Denmark, Moldova, and Belarus.

The festival stand of the ‘NEVER AGAIN’ Association was the venue of a debate with Nay San Lwin, a human rights activist and representative of the persecuted minority of Rohingya in Myanmar (Burma). For years he has been drawing the attention of world public opinion to the genocidal practices used by the military dictatorship against the Rohingya, such as violence, hunger and forced evictions. The genocide in Myanmar has been documented by the United Nations. The other participants of the debates organized by ‘NEVER AGAIN’ included members of Opferperspektive (Victim’s Perspective), a German organization which helps the victims of hate crimes, as well as activists from Denmark, Moldova, and Belarus.

Poland’s Civil Rights Ombudsman Adam Bodnar also participated in a meeting organised by the ‘NEVER AGAIN’ Association during the festival. Mr Bodnar spoke about the recent cases of homophobic violence in Poland. Furthermore, the ‘NEVER AGAIN’ Association organized a football tournament promoting the message of ‘Let’s Kick Racism out of the Stadiums’ among the festival participants. On 2 August, the group’s members played a match with the Ombudsman’s team led by Adam Bodnar himself.

Poland’s Civil Rights Ombudsman Adam Bodnar also participated in a meeting organised by the ‘NEVER AGAIN’ Association during the festival. Mr Bodnar spoke about the recent cases of homophobic violence in Poland. Furthermore, the ‘NEVER AGAIN’ Association organized a football tournament promoting the message of ‘Let’s Kick Racism out of the Stadiums’ among the festival participants. On 2 August, the group’s members played a match with the Ombudsman’s team led by Adam Bodnar himself.

During the festival days ‘NEVER AGAIN’ organized many other educational activities, including public discussions with numerous musicians involved in its ‘Music Against Racism’ campaign and an anti-fascist quiz with the ‘Naprzod’ (Forward) Foundation. The anti-racist educational activity during the festival was supported by Studio K2, the Fare network, and the Warsaw-based Rotary Club Goethe.

During the festival days ‘NEVER AGAIN’ organized many other educational activities, including public discussions with numerous musicians involved in its ‘Music Against Racism’ campaign and an anti-fascist quiz with the ‘Naprzod’ (Forward) Foundation. The anti-racist educational activity during the festival was supported by Studio K2, the Fare network, and the Warsaw-based Rotary Club Goethe.

The ‘NEVER AGAIN’ Association is an independent organization established in Warsaw in 1996. ‘NEVER AGAIN’ has campaigned against racism, antisemitism and xenophobia, for peace, intercultural dialogue and human rights both in Poland and internationally.

More info:

www.nigdywiecej.org

www.facebook.com/Respect.Diversity

www.twitter.com/StowNIGDYWIECEJ

* If you would like to support ‘NEVER AGAIN’ please contact [email protected]

]]>I suddenly found myself thinking it could have been one of my kids in that bag, and that thought upset me more than anything has for a long time.

This letter was originally published on 3 August 2014. Brian Eno is an artist, musical innovator, record producer for artists ranging from David Bowie to U2 and Coldplay. He is president of Stop the War Coalition.

Dear All of You,

I sense I’m breaking an unspoken rule with this letter, but I can’t keep quiet any more.

Today I saw a picture of a weeping Palestinian man holding a plastic carrier bag of meat. It was his son. He’d been shredded (the hospital’s word) by an Israeli missile attack – apparently using their fab new weapon, flechette bombs. You probably know what those are – hundreds of small steel darts packed around explosive which tear the flesh off humans. The boy was Mohammed Khalaf al-Nawasra. He was 4 years old.

I suddenly found myself thinking that it could have been one of my kids in that bag, and that thought upset me more than anything has for a long time.

Then I read that the UN had said that Israel might be guilty of war crimes in Gaza, and they wanted to launch a commission into that. America won’t sign up to it.

What is going on in America? I know from my own experience how slanted your news is, and how little you get to hear about the other side of this story. But – for Christ’s sake! – it’s not that hard to find out. Why does America continue its blind support of this one-sided exercise in ethnic cleansing? WHY? I just don’t get it. I really hate to think its just the power of AIPAC… for if that’s the case, then your government really is fundamentally corrupt. No, I don’t think that’s the reason… but I have no idea what it could be.

The America I know and like is compassionate, broadminded, creative, eclectic, tolerant and generous. You, my close American friends, symbolise those things for me. But which America is backing this horrible one-sided colonialist war? I can’t work it out: I know you’re not the only people like you, so how come all those voices aren’t heard or registered?

How come it isn’t your spirit that most of the world now thinks of when it hears the word ‘America’? How bad does it look when the one country which more than any other grounds its identity in notions of Liberty and Democracy then goes and puts its money exactly where its mouth isn’t and supports a ragingly racist theocracy?

I was in Israel last year with Mary. Her sister works for UNWRA in Jerusalem. Showing us round were a Palestinian – Shadi, who is her sister’s husband and a professional guide – and Oren Jacobovitch, an Israeli Jew, an ex-major from the IDF who left the service under a cloud for refusing to beat up Palestinians. Between the two of them we got to see some harrowing things – Palestinian houses hemmed in by wire mesh and boards to prevent settlers throwing shit and piss and used sanitary towels at the inhabitants; Palestinian kids on their way to school being beaten by Israeli kids with baseball bats to parental applause and laughter; a whole village evicted and living in caves while three settler families moved onto their land; an Israeli settlement on top of a hill diverting its sewage directly down onto Palestinian farmland below; The Wall; the checkpoints… and all the endless daily humiliations. I kept thinking, “Do Americans really condone this? Do they really think this is OK? Or do they just not know about it?”.

As for the Peace Process: Israel wants the Process but not the Peace. While ‘the process’ is going on the settlers continue grabbing land and building their settlements… and then when the Palestinians finally erupt with their pathetic fireworks they get hammered and shredded with state-of-the-art missiles and depleted uranium shells because Israel ‘has a right to defend itself’ ( whereas Palestine clearly doesn’t). And the settler militias are always happy to lend a fist or rip up someone’s olive grove while the army looks the other way.

By the way, most of them are not ethnic Israelis – they’re ‘right of return’ Jews from Russia and Ukraine and Moravia and South Africa and Brooklyn who came to Israel recently with the notion that they had an inviolable (God-given!) right to the land, and that ‘Arab’ equates with ‘vermin’ – straightforward old-school racism delivered with the same arrogant, shameless swagger that the good ole boys of Louisiana used to affect. That is the culture our taxes are defending. It’s like sending money to the Klan.

But beyond this, what really troubles me is the bigger picture. Like it or not, in the eyes of most of the world, America represents ‘The West’. So it is The West that is seen as supporting this war, despite all our high-handed talk about morality and democracy. I fear that all the civilisational achievements of The Enlightenment and Western Culture are being discredited – to the great glee of the mad Mullahs – by this flagrant hypocrisy. The war has no moral justification that I can see – but it doesn’t even have any pragmatic value either. It doesn’t make Kissingerian ‘Realpolitik’ sense; it just makes us look bad.

I’m sorry to burden you all with this. I know you’re busy and in varying degrees allergic to politics, but this is beyond politics. It’s us squandering the civilisational capital that we’ve built over generations. None of the questions in this letter are rhetorical: I really don’t get it and I wish that I did.

In September 2018, Brian Eno alongside a host of artists wrote published an open letter supporting the appeal from Palestinian artists to boycott the Eurovision Song Contest 2019 hosted by Israel. “Until Palestinians can enjoy freedom, justice and equal rights, there should be no business-as-usual with the state that is denying them their basic rights.”

]]>From every corner of the world came sailing, The 5th International Brigade. They came to stand beside the Spanish people to try and stem the rising fascist tide.

Lyrics

Ten years before I saw the light of morning

A comradeship of heroes was laid

From every corner of the world came sailing

The Fifth International BrigadeThey came to stand beside the Spanish people

To try and stem the rising fascist tide

Franco’s allies were the powerful and wealthy

Frank Ryan’s men came from the other side

Even the olives were bleeding

As the battle for Madrid it thundered on

Truth and love against the force of evil

Brotherhood against the fascist clan

CHORUS

Viva la Quinta Brigada

“No Pasaran”, the pledge that made them fight

“Adelante” is the cry around the hillside

Let us all remember them tonight

Bob Hilliard was a Church of Ireland pastor

Form Killarney across the Pyrenees he came

From Derry came a brave young Christian Brother

Side by side they fought and died in Spain

Tommy Woods age seventeen died in Cordoba

With Na Fianna he learned to hold his gun

From Dublin to the Villa del Rio

Where he fought and died beneath the blazing sun

CHORUS

Many Irishmen heard the call of Franco

Joined Hitler and Mussolini too

Propaganda from the pulpit and newspapers

Helped O’Duffy to enlist his crew

The word came from Maynooth, “support the Nazis”

The men of cloth failed again

When the Bishops blessed the Blueshirts in Dun Laoghaire

As they sailed beneath the swastika to Spain

CHORUS

This song is a tribute to Frank Ryan

Kit Conway and Dinny Coady too

Peter Daly, Charlie Regan and Hugh Bonar

Though many died I can but name a few

Danny Boyle, Blaser-Brown and Charlie Donnelly

Liam Tumilson and Jim Straney from the Falls

Jack Nalty, Tommy Patton and Frank Conroy

Jim Foley, Tony Fox and Dick O’Neill

CHORUS

]]>Source: Medium

“The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”

There are times when an individual dares to stand against the prevailing tide of orthodoxy and received truth, and is visited receive with the kind of social anathematisation and obloquy consistent with public persecution at the hands of society’s self-appointed moral, cultural and political guardians.

Such an individual was Paul Robeson, a figure who still today looms imperious as the epitome of unshakeable principle, courage, fidelity and defiance of a status quo mired in hypocrisy and nourished by injustice. In his case, in the process, he succeeded in breaking free of the limitations imposed by a purely racial and national consciousness, embracing a politics rooted in the universal struggles and plight of the working man of all lands, and all races, wherever capitalism and its works midwifed into existence racism, gross inequality, brutal conditions and, in periods of crisis, fascism.

Though such a proclamation might normally come with hyperbole warning attached, where Paul Robeson’s concerned it actually verges on understatement.

Not only did his refusal to buckle during one of the most censorious and neuralgic periods in US history – the years of McCarthyism and the anti-Communist witch hunts – place him on a higher moral plane than most who went before and have come after, the manner in which he was willing to sacrifice a lucrative career in showbusiness and the worldwide acclaim it brought him from the rich and connected, arguably elevates the man to the status of a martyr for free speech, free association, peace and racial and economic justice.

During his appearance before the House Un-American Committee (HUAC) in Washington on 12 June 1956, the following exchange took place:

CHAIRMAN: There was no [racial]prejudice against you. Why did you not sent your son to Rutgers?

ROBESON: This is something that I challenge very deeply, and very sincerely, the fact that the success of a few Negroes, including myself or Jackie Robinson can make up — and here is a study from Colombia University — for $700 a year for thousands of Negro families in the South. My father was a slave, and I have cousins who are sharecroppers and I do not see my success in terms of myself. That is the reason, my own success has not meant what it should mean. I have sacrificed literally hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars for what I believe in.

This passage alone offers a scintillating insight into the factors responsible for shaping Robeson’s worldview, his sense of self and profound understanding of the disjuncture between the national myths that sustained the ‘idea’ of America — liberty, freedom and opportunity — and the acute racial, economic, and social injustice that constituted the ‘reality’.

Just imagine the feeling growing with the knowledge that your father, your flesh and blood from whose seed you were spawned, had been a slave; reduced to human chattel to be treated, mistreated, bought and sold at the whim of another. Imagine the wounding sense of grievance at the knowledge that such a grotesque state of affairs existed in a country that proclaims itself the home of the brave and land of the free, and which prides itself on being a castle of democracy and liberty. Just, for a moment, imagine.

Do so and you cannot fail to arrive at the beginning of understanding relating to the elemental drive for something approximating to justice not only for his own people in America, but the oppressed everywhere, one that consumed Robeson throughout his conscious life.

The old union mantra of ‘an injury to one is an injury to all’ was Paul Robeson’s credo, precisely as it should be when delineating what began as a racial consciousness and was then augmented by a class and political consciousness to forge an unbreakable trinity that imbued his life with a purpose exponentially greater than self.

Here he is in 1949, laying it all out: “My father was of slave origin. He reached as honorable a position as a Negro could under these circumstances, but soon after I was born he lost his church and poverty was my beginning. Relatives from my father’s North Carolina family took me in, a motherless orphan, while my father went to new fields to begin again in a corner grocery store. I slept four in a bed, ate the nourishing greens and cornbread. I was and am forever thankful to my honest, intelligent, courageous, generous aunts, uncles and cousins, not long divorced from the cotton and tobacco fields of eastern North Carolina.

There exists wonderful footage of Paul Robeson singing to Scottish miners in 1949. He looks completely comfortable, natural and at ease in their company, as do they in his; as if in that preternatural instinct possessed by the industrial working class, they sensed that here among them was not a visiting dignitary, arriving in their midst in a spirit of paternalism, but a man who stood with them in solidarity.

In his epic novel Docherty, following the struggles of a family in the fictional mining town of Graithnock in Ayrshire, Scotland at the turn of the last century, author William McIlvanney has the novel’s eponymous hero Tam Docherty declare during a debate with his wayward middle son Angus, “In any country in the world, who are the only folk that ken whit it’s like tae live in that country? The folk at the bottom. The rest can a’ kid themselves on. They can afford to have fancy ideas. We canny, son. We lose the one idea o’ who we are , we’re dead. We’re one another. Tae survive, we’ll respect one another. When the time comes, we’ll a’ move forward together, or not at all.”

Robeson was a man whose values and outlook were forged on the basis of this very sentiment. It is why wherever workers were congregated anywhere in the world, this proud black African-American was at home, whether it be in America, Australia, South Wales, Scotland or Russia. In a 1949 interview, he talked about his struggle to unite working people across the world just as the Cold War was about to forge national amnesia in America and the West when it came to the Grand Allliance between Britain, the US and the Soviet Union that had succeeded in defeating fascism just four years earlier.

Robeson: “I toured England in peace meeting for British-Soviet friendship, did a series of meetings on the issues of freedom for the peoples of Africa and the West Indies, and on the question of the right of colored seamen and colored technicians to get jobs in a land for which they had risked their lives. Ten thousand people turned out to a meeting in Liverpool on this latter issue.” Continues: “I stood at the coal pits in Scotland and saw miners contribute their earnings $1,500 to $2,000 for the benefit of African workers…My role was in no sense personal. I represented to these people Progressive America, fighting for peace and freedom, and I bring back to you their love and affection, their promise of their strength to aid us, and their gratefulness for our struggles here.”

Robeson’s unapologetic solidarity with the peoples of the Soviet Union in a time of fanatical anti-Communism in America guaranteed that the forces of hell would be unleashed against him. Yet like the proverbial Daniel in the lion’s den, not for a minute, despite the career suicide his stance earned, did he flinch or budge. Again, from 1949: “For the progressive peoples of America the memory of the hero-cities Stalingrad, Leningrad, Odessa, and Sevastopol is sacred. Sacred are the names of the defenders of Moscow. We remember them and we will never forget them.”

Paul Robeson’s affection for the Soviet Union, outlined above, was rooted in his unwavering reverence and appreciation of the indispensable role its people played in defeating fascism in Europe during WWII. To him, this world-historical struggle was of seminal importance not only to the people’s of Europe but also Africa and throughout the Southern Hemisphere, given the ideological, political and material support provided to the multiple national liberation struggles against Western colonialism by the Soviets in the pre and postwar period.

The McCarthyite era after the war, wherein after Roosevelt’s death his successor Harry S Truman signed into law the National Security Act, establishing a permanent war economy and vast intelligence apparatus -configured to meet the new demands of the Cold War against Moscow -Robeson viewed as a betrayal of the heroic struggle against fascism. The singer and actor drew a connection between McCarthyism and racial injustice that was being suffered by blacks, particularly in the Deep South, where lynchings were still routine. He drew a strong connection between both of these maladies and fascism.

Robeson: “The essence of fascism is two things. Let us take the more obvious one first: Racial superiority, the kind of racial superiority that led Hitler to wipe out 6,000,000 Jewish people, that can result any day in the lynching of Negro people in the South or other parts of America, the denial of their rights, the constant daily denial to any Negro in America, no matter how important, of his essential human dignity which no other American will accept, this daily insult to the human being.”

Within Paul Robeson raged a sense of justice and hatred of racial and class oppression. He articulated both with uncommon gravitas and sincerity, lending him a majesty which belied the public opprobrium and anathematisation he endured at the hands of men whose collective legacy amounts to a particle of sand in comparison. Internationalism was to him more than a word or even principle it was a non-negotiable condition of human progress. He went wherever exploitation reigned, more at home among workers in mining communities, whether in Russia, Scandinavia, Scotland or Wales than in the grand opulent theatres and venues at which he performed in his time.

Paul Robeson was born 9 April 1898 and died 23 January 1976. Throughout his long life he set bar of fidelity to unshakeable principle so high that very few have come close to reaching it since.The price paid in monetary terms and in terms of the demonisation he was subjected to throughout the postwar period, over his refusal to compromise on his solidarity with the officially designated enemy of a Washington political and security establishment defined not by democracy but white supremacy, was as nothing when set alongside the mammoth legacy he achieved not only as an artist and political activist, but as a man.

In his own words: “The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”

Amen.

]]>You don’t have to look for to see the immense anti-immigration and anti-refugee sentiment that’s spreading within the United States and around the globe. This music video from the Hamilton Mixtape portrays all kinds of immigrant experiences, and the underpaid jobs they often take in the service industry. The sweat-shop like environment of laborers sewing American flags feels especially symbolic—this is a nation built on immigrants that depends on immigrants.

Immigrants (We Get The Job Done)

featuring Residente, Riz MC & Snow Tha Product

And just like that it’s over, we tend to our wounded, we count our dead

Black and white soldiers wonder alike if this really means freedom…

Not yet

[K’Naan:]

I got 1 job, 2 jobs, 3 when I need them

I got 5 roommates in this one studio but I never really see them

And we all came America trying to get a lap dance from lady freedom

But now lady liberty is acting like Hillary Banks with a pre-nup (Banks with a pre-nup)

Man I was brave sailing on graves

Don’t think I didn’t notice those tombstones disguised as waves

I’m no dummy, here is something funny you can be an immigrant without risking your lives

Or crossing these borders with thrifty supplies

All you got to do is see the world with new eyes

[Chorus:]

Immigrants

We get the job done

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

We get the job done

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Immigrants

We get the job done

[Snow Tha Product:]

It’s a hard line

When you’re an import

Baby boy it’s hard times

When you ain’t sent for

Racist feed the belly of the beast

With they pitchforks, rich chores

Done by the people that get ignored

Ya se armó

Ya se despertaron

It’s a whole awakening

La alarma ya sonó hace rato

Los que quieren buscan

Pero nos apodan como vagos

We are the same ones

Hustling on every level

Ten los datos

Walk a mile in our shoes

Abrochenze los zapatos

I been scoping ya dudes

Ya’ll ain’t been working like I do

I’ll outwork you, it hurts you

You claim I’m stealing jobs though

Peter Piper claimed he picked them he just underpaid Pablo

But there ain’t a paper trail when you living in the shadows

We’re Americas ghost writers the credit is only borrowed

It’s a matter of time before the checks all come

But…

[Chorus:]

Immigrants

We get the job done

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

We get the job done

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Immigrants

We get the job done

Not yet

[Snow Tha Product:]

The credit is only borrowed

It’s Americas ghost writers the credit is only borrowed

It’s Americas ghost writers

It’s Americas ghost writers

It’s Americas ghost writers the credit is only borrowed

It’s Americas ghost writers the credit is only borrowed

It’s Americas ghost writers the credit is only borrowed

It’s Americas ghost writers the credit is only borrowed

It’s…

[Part Chorus:]

Immigrants

We get the job done

[Riz MC:]

Ay yo aye immigrants we don’t like that

Na they don’t play British empire strikes back

They beating us like 808’s and high hats

At our own game of invasion, but this ain’t Iraq

Who these fugees, what did they do for me

But contribute new dreams

Taxes and tools swagger and food to eat

Cool, they flee war zones, but the problem ain’t ours

Even if our bombs landed on them like the Mayflower

Buckingham Palace or Capitol Hill

Blood of my ancestors had that all built

With the ink you print on your dollar bill, oil you spill

Thin red lines on the flag you hoist when you kill

But still we just say “look how far I come”

Hindustan, Pakistan, to London

To a galaxy far from their ignorance

Cause immigrants, we get the job done

[Residente:]

Por tierra o por agua

Identidad falsa

Brincamos muros o flotamos en balsas

La peleamos como Sandino en Nicaragua

Somos como las plantas que crecen sin agua

Sin pasaporte americano

Porque la mitad de gringolandia es terreno mexicano

Hay que ser bien hijo de puta

Nosotros les sembramos el árbol y ellos se comen la fruta

Somos los que cruzaron

Aquí vinimos a buscar el oro que nos robaron

Tenemos mas trucos que la policía secreta

Metimos la casa completa en una maleta

Con un pico, una pala

Y un rastrillo

Te construimos un castillo

Como es que dice el coro cabrón?

[Chorus:]

Immigrants

We get the job done

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

We get the job done

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Immigrants

We get the job done

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Look how far I come

Immigrants

We get the job done

Not yet

]]>Source: Counterpunch

She will simultaneously flip the bird to millions of Palestinians who languish under a brutal system of colonial oppression and ethnic cleansing.

It may be difficult for some to understand the impact that a pop icon has on social and political events, but these cultural figures possess enormous psychological sway in the minds of millions. Their actions make a difference. So it can be quite jarring when one of those icons goes against the justified demands of an entire people, especially when they have been oppressed and persecuted for decades.This May Madonna is set to perform two songs at Eurovision in Tel Aviv. She will reach an estimated 180 million viewers. She has moneyed backing too. Canadian billionaire Sylvan Adams has pledged to pay $1 million dollars for her performance at Eurovision. And she will simultaneously flip the bird to millions of Palestinians who languish under a brutal system of colonial oppression, ethnic cleansing and apartheid. Madonna is no stranger to this controversy. In 2012 she launched her MDNA tour in Tel Aviv against the urging of BDS activists.

There is a dark legacy of pop icons who play in places where there is rampant oppression or injustice. In the 1980s scores of artists played Sun City, a resort in the Bantustan state of Bophuthatswana. A state with limited autonomy created by the racist regime of apartheid South Africa in order to forcibly displace Black South Africans from their lands. Dolly Parton, Elton John, Frank Sinatra and Liza Minelli were among the big headliners there and reportedly received millions for their performances. In 2009, Sting reportedly got £1 million playing for Gulnara Karimova, the daughter of the notorious repressive leader of Uzbekistan. He was unrepentant about that gig.

In 2015 Nicki Minaj played for Jose Eduardo dos Santos, the repressive president of Angola who has been widely associated with human rights abuses and corruption. But Minaj wasn’t fazed by criticism. In fact, she laughed it off and inadvertently exposed the real reason these artists play in such venues in the first place. On Instagram she posted a photo of her and the daughter of dos Santos saying “Oh no big deal… she’s just the 8thrichest woman in the world…. GIRL POWER!!!!! This motivates me soooooooooo much!!!!”

And therein lies the answer. Pop artists are products of an industry that is obsessed with wealth accumulation and privilege. In fact, they celebrate it as a virtue and promote the fallacy that wealth equates with liberation movements like feminism, personal success and agency. It is a fallacy that “motivates”them, as Minaj revealed.

Indeed, the music industry, especially under late stage capitalism, churns out a banal formula for success, one deeply associated with wealth and power, uninterested in social, environmental or political movements. It shouldn’t be surprising then that most pop stars are consumed with this. They, like so many in the art and movie industry, are captivated by the excesses, bling and thrill of being connected with the powerful. Ethics be damned.

Many pop stars claimed in the aftermath of playing in repressive places that they were ignorant of the human rights, economic or environmental abuses. But Madonna cannot make that claim. In 2016 she paid $20 million dollars for a two story penthouse in Tel Aviv. She undoubtedly sees the headlines on Haaretz.

She knows what is happening in that city to African migrants and refugees who are routinely demonized and persecuted by politicians and rightwing fascists. Migrants who are sent to internment camps in the Negev.

She has undoubtedly heard about the Nakba and the refugee camps, and knows all too well what is happening now in the occupied West Bank and Gaza.

She knows that Israel maintains a US funded army, navy and air force, and the Palestinians do not. She knows Israel has blockaded Gaza since 2007, subjecting nearly 2 million people to intolerable conditions that amount to collective punishment. Indeed, Gaza has been declared “unlivable”in many regards by the UN.

She knows scores of unarmed protestors, as well as reporters and medics, have been gunned down in cold blood along the Gaza fence.

She knows about the checkpoints, settlements and the settler violence against Palestinian school children and villagers. She knows about the environmental terrorism of slashed olive trees and poisoned wells.

She knows millions of Palestinians are subject to Israeli rule under the occupation without equal representation, the very definition of apartheid.

She knows about the wall of separation that limits Palestinian access to their jobs, farmland, medical facilities and schools.

She knows Palestinians homes in the occupied West Bank are routinely demolished. And that scores of children are routinely whisked away in the middle of the night with no warning by the IDF, and taken to undisclosed detention facilities where they are often subjected to threats and violence and placed in solitary confinement, and then subjected to military tribunal unlike their Jewish counterparts who enjoy access to civil courts.

She knows that Israel periodically flattens parts of Gaza killing scores of people with block decimating bombs and white phosphorus. And she knows that under the racist Trump regime Israeli crimes against humanity have been given complete impunity.

In addition to this, Madonna knows this is not really about “building bridges of peace and understanding.” She knows that there are millions of Jews around the world and many Israelis who vociferously and courageously oppose the occupation, apartheid and the continued oppression and dispossession of the Palestinians. People who are horrified at the fascistic lurch Israeli society has taken, especially in recent elections. People from organizations like If Not Now who represents Israeli soldiers who are speaking out about what they have seen and have been asked to do, and Jewish Voice for Peace who have implored her not to artwash or even pinkwash apartheid and to stand on the right side of history.

She knows that there has been a call by Palestinian civil society for a non-violent boycott of Israel as long as it continues to commit these ongoing crimes. But she ignored them then, and she will undoubtedly ignore them now.

So for those expecting more out of Madonna they are bound to be disappointed. And this may be a hard pill for some to swallow at first. After all, I remember growing up and coming out to Madonna tunes. Her liberated sexuality and avant-garde style (at least in regard to Hollywood culture) was refreshing for a youth immersed in a society of puritanical repression and rigid social mores. In truth, I still listen to some of her songs on occasion when I wax nostalgic. Those icons represent a torch for many youth looking for a way out from under the boot of reactionary authoritarianism. But somewhere along the line something changes for most people with a conscience. The icons are forced to descend from their pedestals and become human, and like any human, they are understood to be subject to the enticements and corruption of coin and privilege. In truth, they cannot be expected to be anything more than a product of an ethics devoid industry and economic order itself.

Millions of people will watch Madonna perform at Eurovision, a European musical contest ironically being held in the Middle-East, Europe’s last enduring colony. She will present Tel Aviv as a bastion of European values in a hostile environment, surrounded by savages. Her message is a new branding for an old orientalism writ large for a new generation.

One can only hope that her performance will cause some to dig deeper and see that human rights are either universal or they are nothing. And that there is no justification for playing apartheid. Not in South Africa 40 years ago. Not in Israel and Palestine today.

“As the refugee crisis rumbles on and compassion appears to wilt against the fiery politics of hate, RIBS is a meditation on our collective failure to uphold the supposedly fundamental European values of respect for human dignity and human rights.” – Filmmaker Emile Ebrahim Kelly.

• RIBS by Hejira is on the album Thread Of Gold (Lima Limo Records)

• Download and stream RIBS here

Lyrics

There are promises in places that I’ve left behind

So far from home

There are secrets that are buried deep within the mind

That we both can’t let go

All the noise that’s building up inside my chest

Fighting to catch my breath

When will the pressure drop, will I feel the air again

Pulling me closer to you

You keep building these walls that I can’t climb

Barricading the doors, leaving me behind

All the strangers surrounding us we just don’t know

Telling us where to go

All the vitals are failing us in our time of need

Who should we beg to breathe?

When it feels like our bruises and burns will never heal

Jaded by all the pain

All the blood it takes to make a life, to take a life

To save a life

You keep building these walls that I can’t climb

Barricading the doors, leaving me behind

At the edge of the water with no way to cross over

I don’t want to walk away

I don’t want to leave this all behind

These ribs will protect you

These broken ribs will protect you

If I don’t belong here, where do I belong?

Everything seems alien, everything seems different

These ribs will protect you

These broken ribs will protect you

Will I be the same again?

These rings around my heart

These rings around my lungs

I can’t breathe anymore

These ribs will protect you

These broken ribs will protect you

These ribs will protect you

These broken ribs will protect you

These ribs will protect you

These broken ribs will protect you

The words of this song by Jim Page are based on letters that human rights activist Rachel Corrie wrote home to her parents before she was crushed to death on 16 March 2003 by an Israeli military bulldozer as she tried to prevent it demolishing the home of a Palestinian doctor. Rachel was 23-years-old.

SEE https://rachelcorriefoundation.org

you know I was always the one

I could never stand idly by

and watch while the bullies beat up on the weaker ones

I had to do something to try

and I never gave up on people

that we could be better somehow

morality’s compass, you gave it to me

I still follow it now

well, I couldn’t stop thinking about it

I couldn’t get it out of my mind

the pictures, the stories, the plight of the people

in occupied Palestine

how my government makes me complicit

with the political aid that they send

so I packed up my bags and I headed to Rafa

to work with the ISM

and I’d rather be dancing, dancing and falling in love

but if I just can just watch from a distance then what am I made of

mama these people are so good to me

they treat me like one of their own

they feed me and see to my needs

and let me sleep in their home

papa their lives are so hard

the gun shots night

the road blocks, the strip searches, the humiliations

papa it just isn’t right

I can feel my privilege around me

it’s there in my American face

I could wave my passport around like a flag

and I would be safe in this place

for these child soldiers of Israel

they look like the boys back home

and if it wasn’t for American money

they’d have to leave these people alone

and I’d rather be dancing, dancing to Pat Benatar

but somebody has to do somethin’ about it and here we are

the tractors are coming today

they’re like tanks with bulldozer blades

the name on the side says Caterpillar

that means they’re American made

well, I am American too

and I’ll be where everybody can see

so if they want to run over these houses today

they’re gonna have to run over me

it’s dangerous takin’ a stand

but it’s dangerous running away

sometimes you have to face up to the danger

there is just no other way

for there are such beautiful dreams

I have seen the eyes of a child

and if I can just make one little difference

then I think my life is worth while

and I’d rather be dancing, but instead I’m saying goodbye

but we’ll meet again when it’s over, don’t cry

and I’d rather be dancing, and surely we’d all rather be

and one day we’ll dance in a world that’s peaceful and free

Source: LetterPress. Reprinted from August 2016

Rock Against Racism was a social movement that is not given its full due when histories of Punk and post-Punk are talked about.

Forget what you’ve seen on nostalgia television, Britain in the mid-1970s was not a groovy place to live in. For most of us it wasn’t disco glitterballs, Chopper bikes and Glam fashion but economic depression, brown and orange furnishings, horrible shirts and jackets with HUGE lapels and endemic, casual racism.The legacy of Enoch Powell’s ‘rivers of blood’ speech was rippling through the population and attacks on members of the Black and Asian population were escalating alarmingly. It is from this potent social soup that punk would be born – a movement itself split between its racist fringe and a more politically progressive caucus.

Although there were those of us on the Left who were trying to stand against the trend towards racist violence – witness the formation of the Anti-Nazi League – there were messages of incitement coming from some seemingly unlikely directions.

In August 1976 a heavily intoxicated Eric Clapton blurted out some very unfortunate remarks onstage at the Birmingham Odeon in England. “England is overcrowded,” he said. “I think we should send them all back.” He went on to add that England was in danger of becoming a “black colony.”

Around the same time, David Bowie caused an even greater uproar when he shared some surprising political beliefs. “I believe very strongly in fascism,” he told Playboy. “The only way we can speed up the sort of liberalism that’s hanging foul in the air. . .is a right-wing totally dictatorial tyranny. . .Rock stars are fascists, too. Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars.”

Fortunately, there were those who loved music and were outraged by this turn of events and, prompted by a letter to the music press by photographer and political activist, Red Saunders, a call went out for people to support a new initiative – Rock Against Racism (RAR).

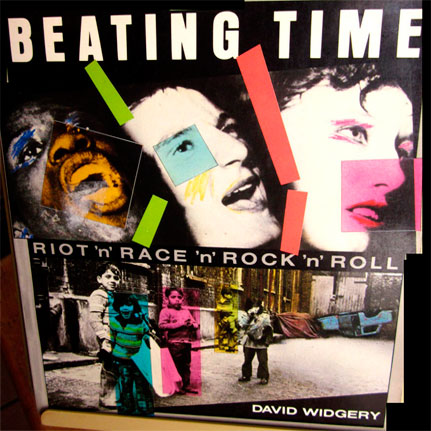

There followed a series of gigs in support of the cause and, hooking into support from emerging punk bands like The Clash and a coming together with the Anti-Fascist League, RAR began to grow. Many mark the official launch date as April 1978 when a march across London was organised, partly as a response to the racist murder of garment factory worker Altab Ali, and which would culminate in a rally in Victoria Park. The turn-out proved to be huge, drawing supporters from across the UK, and a fully fledged movement was born.David Widgery, who put together Beating Time, was there from the very beginning and brings a uniquely informed and almost intimate portrait of how RAR grew and developed. He uses contemporary reportage with original images and newspaper coverage to piece together the history of the movement.

What soon became clear was that campaigning against racism wasn’t just about trying to confront a single issue – racism exists because of the wider political context in which prejudice and discrimination can flourish. As the final years of the moribund Labour government conceded power to the emergent neoliberalism embodied by the Thatcher regime, RAR found itself campaigning for wider issues of social justice well into the 1980s.

Widgery’s book was published in 1986 and although this doesn’t mark the end of the RAR story it was its high water mark. In the following years RAR mutated into many other anti-racist campaigns that the author of this book insightfully anticipates in his final chapter. You will find this book an excellent introduction to a social movement that is not given its full due when histories of Punk and post-Punk are talked about. Writing in The Guardian in 2008 Safraz Manzoor notes:

“Thirty years after the Victoria Park carnival the story of Rock Against Racism is only fleetingly mentioned in most histories of punk, but that does not diminish its extraordinary achievement. It’s an achievement that can perhaps only be gauged by imagining how else things might have been had Red Saunders not been moved to write that letter, had courageous souls like Roger Huddle, Paul Furness and the rest not joined the movement: Eric Clapton would have got away with making racist comments, the National Front would have continued to march into immigrant areas stirring up hatred, winning votes and seats and the course of British politics could have been very different.”

The Clash at Rock Against Racism carnival 1978

SEE ALSO:

- What the Anti-Nazi-League and Rock against Racism teach us about how to defeat the fascists. By David Renton

- How Rock Against Racism created a climate in which being racist was not acceptable.By Patrick Sawer

- Raves, riots and revolution: can the political power of music help to change the world? By Dave Randall

He fought for the people of Chile / With his songs and his guitar / His hands were gentle, his hands were strong. Words by Adrian Mitchell. Music by Arlo Guthrie.

Victor Jara

Lived like a shooting star

He fought for the people of Chile

With his songs and his guitar

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

He worked from a few years old

He sat upon his father’s plow

And watched the earth unfold

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Or one of their children died

His mother sang all night for them

With Victor by her side

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Against the people’s wrongs

He listened to their grief and joy

And turned them into songs

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

And those who worked the land

He sang about the factory workers

And they knew he was their man

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

Working night and day

He sang “Take hold of your brothers hand

You know the future begins today”

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

They arrested Victor then

They caged him in a stadium

With five-thousand frightened men

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

His voice was brave and strong

And he sang for his fellow prisoners

Till the guards cut short his song

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

They beat him on the head

They tore him with electric shocks

And then they shot him dead

His hands were gentle, his hands were strong

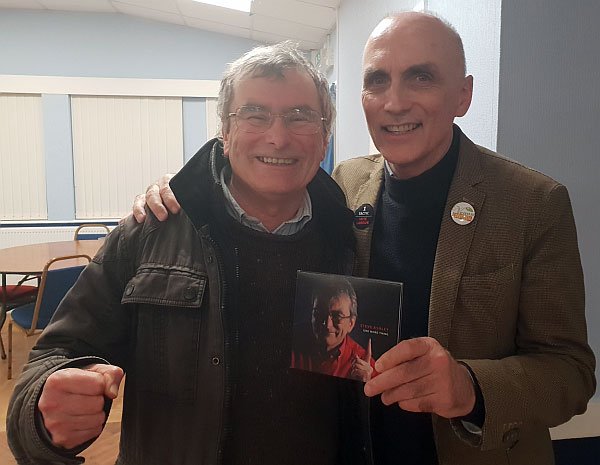

Steve Ashley’s latest album is already picking up rave reviews in the music and political media.

Theresa May, Donald Trump, The Windsors, George Clooney, The White Helmets, riot police, ‘terror correspondents’ and war-hungry politicians – all come under the closest scrutiny in Steve Ashley’s new album, titled One More Thing – amid the stunning melodies and fine English poetry that have hallmarked Steve Ashley’s creative output ever since his legendary 1974 debut, ‘Stroll On’.Dare to question all you see…, he says, on the last track of this, which he has announced as his final album, and true to his word he does exactly that throughout this radical collection of songs.

Far from splenetic, good humour abounds as a gentle yet firm hand steers us through his latest musical essay into the state of our nation, and how leaders seek to manage our lives.Given to a light chuckle on occasion here, Ashley even collapses into laughter at the end of one song.

One More Thing is a showcase for fine English folk songwriting, one that sets contemporary issues within a traditional construct. Dynamic, challenging and inspiring: this album marks the end of a highly original and distinctive solo career.

The Morning Star, gave the album a 5-star review – for “songs casting a critical eye on everything from right-wing politicians, the royal family, religion and reporting by the corporate media”:

“Ashley insists that this really is his last album, but his involvement in left-wing politics meant he couldn’t resist the temptation to retire disgracefully. Any Star reader listening to this album might hope there’s a chance of at least a bit more disgrace before final retirement.”

The early reviews have all been similarly complimentary. David Kidman at Folk Radio writes:

“Even if Steve sticks to his guns and never makes another album, you can bet that he’ll still find plenty more to say about this world – the watchwords of grit, determination and integrity will stay with Steve to the end.”

Oz Hardwick, writing in Rock and Reel, which also gave the album a 5-star rating, calling it ‘understated and vital’:

“One More Thing‘s success is down to the warmth and humanity, the concern for the individual, which underlies these big themes. For every self-serving politician, there are many more ordinary yet remarkable people who will knock on doors, join marches, and simply question prevailing rhetoric, and these songs are for anyone who stands up for what is right.”

One More Thing

One More Thing

by Steve Ashley

Available here…

]]>

Steve O’Donoghue wrote this song about his grandfather Arthur. ‘He joined up as a boy, lying about his age. He was a sort of yellow colour due to the mustard gas. He never talked about the war, except to say, “I’ve seen things no man should have to see.”’

Arthur was not keen on poppies being used to glorify war. A better image for him was the dandelion, its seeds blown away in the wind.

Dandelions: Lyrics

Now Arthur was only a young cub

A brave lion and merely fifteen

But with the rest of his pack

He was sent to attack

To a war that was cruel and obscene

But those lions fought hard and fought bravely

While the donkeys just grazed in a field

They had no sense of shame for their barbarous game

And the thousands of lions they killed

And when he saw them marching up Whitehall

I remember what old Arthur said

He said the donkeys are all wearing poppies

So I shall wear dandelions instead

Now every remembrance sunday

Well I pause at eleven o’clock

And I remember those dandy young lions

And those donkeys and their poppycock

Cos they’ve taken those beautiful poppies

And they use them to glorify war

Well I remember those dandy young lions

And I don’t wear a poppy no more

And when he saw them marching up Whitehall

I remember what old Arthur said

He said the donkeys are all wearing poppies

So I shall wear dandelions instead

Now if you take an old dandelion

And just blow it quite gently he’d say

You can see all the dreams of those soldiers

In the seeds as they just float away

But then the wind takes hold of those seeds

And they rise and quickly they soar

Like the spirit of all those old soldiers

Who believed that their war would end war

And when he saw them marching up Whitehall

I remember what old Arthur said

He said the donkeys are all wearing poppies

So I shall wear dandelions instead

Cos those lions were dandy young workers

Who those donkeys so cruelly misled

And if the Donkeys are gonna wear poppies

I shall wear dandelions instead.

And when he saw them marching up Whitehall

I remember what old Arthur said

He said the donkeys are all wearing poppies

So I shall wear dandelions instead

If you’re old enough to remember those who fought in World War One, they bore dignified witness to the insanity of war.

When I was a kid, I used to run errands for a old man who lived a few doors down from our house. His name was Will Vernon and he was the only World War One veteran that I knew.He was pushing 70 in the late 1960s and had a debilitating cough, all wet and spluttery, an echo of the trenches where he was gassed as a teenager, aged 19.

Will used to give me half a crown to do his weekly shopping, which was a lot of money to a 10 year old.

I happened to see an advert on Facebook offering free access to WW1 records and, thinking of old Will Vernon, I decided to put his name into their search engine where I quickly found his war records.

He was a rifleman in the 3rd Rifle Brigade, fought in the breakthrough of the Hindenburg Line and was admitted to hospital having been gassed on 12th October 1918.

If you’re old enough to remember those who fought in WW1, they bore dignified witness to the insanity of war.

I was briefly a squaddie myself and I’ve found that experience has helped me to oppose war, but not demonise soldiers.

The guys I served with were just like old Will Vernon, teenagers put in a difficult situation without the right equipment – where was his gas mask? – and some loving family’s son.

Billy Bragg: Remembering WW1 veteran Will Vernon

In his tribute to Will Vernon, Billy Bragg performed his classic song Between the Wars at the No Glory in War concert on 25 October 2013.

]]>Source: Counterpunch

Unlike Waters, who connects with Gaza, the biggest open prison in the world, Bono goes out of his way to connect with the EU corporatist project.

Listening to the politics of Roger Waters is rock and roll. The Pink Floyd genius is now the most prominent voice of the BDS movement that is defending Palestinian rights. At the moment, it feels like Waters is the only white man taking on the state of Israel (not forgetting the brilliance of Finkelstein). Indeed, considering the fact that Israel is the heart of Western geopolitics–the true target of Waters’ activism is the Western Empire itself. And he knows it.In contrast, when listening to Bono pontificate, we hear bombers flying overhead. While Waters was in St. Petersburg this September, on tour, Bono was to be found in Paris, also on tour, but meeting up with the French President, Emmanuel Macron, as well. The U2 mediocrity claimed afterwards that he and “the bomber of Syria” were talking about Africa. It was the continuation of a discussion Bono began years ago with “the bombers of Iraq”–Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and George W. Bush.

Waters and Bono come from two different cultures: Waters from the 1960s and Bono from the 1980s. Pink Floyd’s debut album was released in 1967, while U2’s debut album saw the light in 1980. This is significant, because the bandleaders of both groups appear to have absorbed the politics of their formative years. Revolution in the case of Waters, and counterrevolution in the case of Bono. And the words of both today, respectively, continue to give expression to progress on the one hand, and regress on the other.

The culture wars between the 1960s and 1980s, between the culture of Che Guevara and the culture of Ronald Reagan, never went away. Beneath the current battle between populism and its elite critics, the undercurrents of class, imperialism and anti-imperialism are as strong as ever. And even millionaire musicians are pulled one way or the other.

In an interview with RT, in St. Petersburg, Roger Waters summed up in one word the culture of Che Guevara (the anti-imperialist culture) which he is perpetuating. That word is “empathy”. The ability to connect with another’s pain or suffering. And the will to fight to end this pain or suffering, basically sums up the attitude of Che and the “1960s”.

This attempt to understand the weak or vulnerable “other” motivates Waters’ support of the Palestinians today. In fact, “empathy” forces him to open up to Russia. In his RT interview, he tells us that during his concerts–in response to the anti-Russian psy-ops which distorts the West today–he asks his audience: “do you know that Russia sacrificed twenty million of its people, so that you can be free of Nazism?”

Bono doesn’t ask this question. Instead, during his current live shows, he wraps himself up in the flag of power. And shamelessly declares his love of the Empire that’s attacking Russia, with sanctions and up close coups, and war games. The flag is that of the European Union. And the Empire is the iron fist that hides behind that flag: NATO.

Unlike Waters–who wants to connect with the biggest open prison in the world: Gaza–Bono goes out of his way to connect with the corporatist project that is the EU. Forget the weak and vulnerable, within the EU, being bombed by austerity, and being dragged into war after war – Bono’s main concern is defending the flag of the super state.

In a Europe dominated by corporations and their lobbyists: Bono’s words and actions are those of an ultra elitist. Listen to his EU-speak: ‘Well, U2 is kicking off its tour in Berlin this week, and we’ve just had one of our more provocative ideas: during the show we’re going to wave a big, bright, blue EU flag…..to some of us it has become a radical act.’

Bono ends this piece in a German newspaper with the usual delusion: ‘I feel privileged to have witnessed the longest stretch of peace and prosperity ever on the European continent.’

The fact that the EU itself has ended whatever “peace and prosperity” there was in Europe, completely undermines Bono’s sinister “blindness”. By imposing neoliberalism, bailouts, austerity and NATO’s wars (Libya, Syria, Ukraine and Russia) upon Europe, the EU has delegitimized itself. Is it therefore right for Bono to defend this state of affairs, or is it radically right wing?

In his interview with RT, Roger Waters says that there’s always a right and a wrong thing to do. In the context of Palestine, the boycott of Israel is the right thing to do. It is so because the boycott stands on the shoulders of history. Waters points to the 1948 declaration of universal human rights–which itself rests on every slave revolt in the past. Anything which aids this trajectory of humanity is righteousness for itself.

There’s no greater slave revolt today, than that of the Palestinian resistance to Israeli occupation. In fact it’s the lynchpin to the struggle for global justice. Today’s great crime against humanity is Western warmongering in the Middle East (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen). And the basis for this is the Western war against Palestine, which began in 1917. In short, the Western Empire today revolves around the repression of Palestine.

This, of course, means that Israel is not alone. Without the support of the USA and EU, Israel wouldn’t last a day. Israel works for the West. Therefore, to boycott Israel is to boycott the West and its reign of terror. This is were Bono comes in. His concern is not Africa but Western weakness. And his job is to prop it up.

Bono correctly discerns the weakness of the EU today. The European people are actually boycotting it. Their votes are saying no to the idea of ‘the EU über alles’. They don’t want another Roman Empire, another Charlemagne, another Holy Roman Empire, another Pax Romana in the Mediterranean Sea. Indeed, they don’t want another Third Reich. They don’t want to make Europe Great Again. But Bono does.

And Roger Waters doesn’t. He places humanity before the West. And is willing to abandon the West in order to achieve a better world. His music, therefore, is a universal act of resistance, whereas Bono’s is a provincial act of imperialism. By holding up the flag of the EU, Bono is flying the flag of Israel and burning the flag of Palestine. In the language of Waters then: Bono is a Pig.

We, on the other hand, who boycott Israel and the EU are human. We’re children of the 60s. We’re sticks of dynamite in the Wall.

Aidan O’Brien lives in Dublin, Ireland.

]]>They dismissed not just her and her message. They went on to label her a terrorist despite having zero grounds for doing this.

The year 2019 will mark a decade since the end of the deadly Sri Lankan civil war, which left up to 150,000 of the Tamil minority unaccounted for or ‘forcibly disappeared’. Nearly ten years on, Tamils are still fleeing human rights abuses and torture as they have done since the war began in 1983. One Tamil refugee was 9-year-old Mathangi Arulpragasam, known by her friends as Maya.Today Maya goes by the stage name, MIA. In a new documentary, Matangi / Maya / M.I.A, we learn about all the Mayas: the rapper, global pop star, visual artist, activist, mum and immigrant.

Maya was raised in Sri Lanka and India with her two siblings, her mother and her father, a Tamil activist. During the civil war, Maya, her mum and siblings were forced to become refugees and fled to London.

As a teen, Maya documented her life on a London council estate, her family and anyone willing to talk to her video camera. A key theme emerges early in the film: You can’t talk about the struggle without talking about the struggle. Director Steve Loveridge’s mix of candid family discussions with the pop star’s relentless challenging of the media and the music industry, creates a lucid illustration of what has made Maya/MIA controversial as an artist.

Of the many controversies surrounding MIA, her biggest affront has been her existence as a Tamil voice in Western media who insists on talking about the Tamil struggle.

Her popularity increased. As it did, the war in Sri Lanka escalated further and further, to the point where massive loss of life was imminent. She worked her platform at every opportunity – on national TV, at the Grammys, in her music videos – to speak about the plight of Tamils in Sri Lanka.

Literally everyone dismissed her message that the mass murder of Tamil civilians was nearing the point of genocide. The media turned a blind eye to Sri Lanka’s war crimes, choosing to spill more ink on the demonisation of MIA. They dismissed not just her and her message. They went on to label her a terrorist despite having zero grounds for doing this.

The film doesn’t go so far as to question Britain’s role in the Sri Lankan civil war. The conflict followed 132 years of British colonial rule, in which British Ceylon replaced the Sinhalese monarchy. British colonialism worsened divisions between the high-caste Sinhalese majority and Tamil minority. After Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, Sinhala legally became the official language of Sri Lanka, followed by anti-Tamil riots and land grabs of Tamil homelands.

MIA continues to advocate against the mistreatment and abuse of Sri Lankan Tamils, refugees and migrants. No one else has been doing this, suggests Radheyan Simonpillai of Now Toronto: ‘Name a popular musician who addresses refugee concerns – Syrian or Mexican, for example – in their songs. You end up right back at M.I.A.’

Ironically, Toronto-based critic Simonpillai forgets to mention K’Naan. Somali-Canadian rapper, K’Naan, settled in Toronto at age 13 with his mother and two siblings after fleeing civil war in Somalia. K’Naan became ‘Somalia’s loudest musical voice in the Western Hemisphere.’ However, he cut off his foray into pop stardom after being told to water down his lyrics: ‘I come with all the baggage of Somalia – of my grandfather’s poetry, of pounding rhythms, of the war, of being an immigrant, of being an artist, of needing to explain a few things.’

Yet both artists grew up on a US tradition of rap that bases a good part of its rhymes on the fight against oppression, violence and poverty. There’s a double standard here, because a refugee rapper in London or Toronto speaking about civil war in Sri Lanka or Somalia, and Tupac Shakur speaking about gang war in Los Angeles are the same.

‘If you come from the struggle, how the fuck do you talk about the struggle without talking about the struggle?’ Zoom out and MIA answers her own question in a striking passage from the film:

“The kid in a village in Coromandel where we shot the Bird Flu video, and the kid in Liberia playing on that playground is exactly the same. And they have nursery rhymes and they play games. They have an opinion about what kind of hairstyle they want and what t-shirt they’re going to put on in the morning. And they have dreams. And they have … an idea of what they want to be.”

People have always migrated. Children have always dreamed about what they want to be. And artists have always expressed themselves. When refugee children become artists, you better believe they will talk about the struggle.

Matangi / Maya / M.I.A is out now in the UK, and opens on 28 September in the US and on 5 October in Canada. For more locations, check: www.miadocumentary.com

Matangi / Maya / M.I.A Official Trailer

Borders. Video directed by MIA

MIA – P.O.W.A

]]>Source: The Telegraph

The sight of black, white and Asian kids enjoying music together undermined the far-right credo that the races were intrinsically hostile to each other.

Forty years ago, on April 30 1978, tens of thousands of people took part in a huge march through London, from Trafalgar Square to Tower Hamlets to protest against rising levels of racism. There, among the trees at Victoria Park, bands such as the Clash, Birmingham reggae stars Steel Pulse and X-Ray Spex, whose singer was a mixed-race girl from Bromley with the inimitable name of Poly Styrene, performed to a crowd that by early evening had swelled to as many as 100,000.Many had travelled from all over the country: 42 coaches came from Glasgow alone. I, too, was there, a teenage punk rocker who came down by coach from Oxford and was painfully conscious of the suspicious stares from some of the white East Enders watching as we made our way to Victoria Park.

But in the park we were greeted by hundreds of black and white teenagers, fellow punks, rastas, skinheads, soul boys and ageing hippies: people from all sorts of backgrounds who had come together to fight racial prejudice.

Looking back it’s no exaggeration to say that concert, organised by a grass roots organisation called Rock Against Racism, not only paved the way for blockbuster benefit gigs such as Free Nelson Mandela and Live Aid, but helped fundamentally change attitudes to race in Britain.

Initially unsure whether the Victoria Park carnival would find an appreciative audience, the organisers anticipated at best that 20,000 people would turn up. Instead, in the words of the late veteran anti-fascist campaigner Gerry Gable, the event would prove to be “one of the most important cultural events of the postwar period”.

The black campaigner Darcus Howe, who died last year, said that he had fathered five children in Britain and that while the first four had grown up angry, thanks to Rock Against Racism his fifth had grown up “black and at ease”.

Today we are used to musicians aligning themselves with good causes. But back in the mid 1970s Rock Against Racism was one of the first movements that asked pop stars to take a stand on race. And at that point picking sides well and truly mattered. Racial tension on the street was dangerously high.

In 1977 the far-right National Front knocked the Liberals into fourth place in the Greater London Council elections, winning 119,000 votes. In east London, Asians were being subjected to vicious attacks – 110 alone between January 1976 and August 1978 – culminating in the murder of Kenneth Singh in Plaistow in April 1978.

Ironically the flame that sparked the birth of RAR was kindled by bigotry within rock music itself. In August 1976, Eric Clapton drunkenly championed Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech while performing in Birmingham. He declared that Britain was becoming a “black colony” and that he wanted “foreigners out”. It was the spur that the photographer Red Saunders and his friend, the designer Roger Huddle, who had been thinking about setting up an organisation to combat racism, needed.

They penned a furious response to Clapton in the form of an open letter in the New Musical Express. “Half your music is black,” they wrote. “You’re a good musician, but where would you be without the blues and R’n’B?” They encouraged readers to get behind the then fledgling RAR. “We want to organise a rank-and-file movement against the racist poison in music. We urge support for Rock Against Racism.”

“It was an emergency,” Saunders says now. “People were being attacked and murdered.” From the beginning his chosen mode of protest was to champion rock’s black roots. “We were music fans looking for a way for ordinary kids who loved black music to have a voice. Out of that came a youth campaign that wasn’t about boring old-fashioned politics, but harnessed the energy of new sounds like punk and reggae.”

Rock Against Racism marked the point when politics and music came together to fight a common enemy. In May 1977, Peter Hain, the future Northern Ireland Secretary; Ernie Roberts, later a Labour MP, and Paul Holborow, a Socialist Workers Party activist, set up the Anti-Nazi League in an attempt to undermine the credibility of the National Front and expose it as racist.

Their objectives chimed with the preoccupations of the then nascent punk movement, as bands like the Clash and the Sex Pistols started aligned themselves with reggae, undermining fascist attempts to woo white youths.

“Racism was totally in-your-face then,” says Don Letts, the DJ who introduced punks to black music by spinning dub and reggae records at The Roxy club in Covent Garden in the 1970s. “If I wasn’t being chased by the National Front I was being stopped by the police using the ‘sus’ laws. But the Clash and the Sex Pistols grew up with black people living next door, and I bonded with them as friends through our love of black music. We came together through an understanding of our differences. Punk and RAR were immeasurably important at street level because they created a mutual respect.”

In August 1977, the ANL took the controversial decision to confront the National Front on the streets, mounting a huge demonstration that broke up an NF march through Lewisham, in south east London. Meanwhile, RAR started organising gigs and discos, starting at the Royal College of Art and culminating in the Victoria Park Carnival.

The sight of black, white and Asian kids enjoying music together did much to undermine the credo of the far-right that the races were intrinsically hostile to each other and could not mix on an equal footing. Nor was it just about racism: at Victoria Park, Tom Robinson had urged the crowd to join in with the chorus of his groundbreaking song Glad to be Gay, this at a time when the few visible gay figures were effeminate stereotypes lampooned in TV sit coms.

Two more RAR concerts followed in south London’s Brockwell Park and Leeds, and later a string of concerts up and down the country that brought together white, black and multiracial punk, funk, soul and reggae bands on the same stage, in many places for the first time.

In the years that followed, this emerging multiculturalism was reflected on TV, as Two Tone bands such as The Specials, Selector and The Beat gained commercial success.

In 1988, musicians from all backgrounds came together at Wembley to stage the huge Free Nelson Mandela concert, in protest against the long imprisonment of the anti apartheid leader. “Jerry Dammers, who organised the Wembley concert, was inspired by Victoria Park,” says Billy Bragg, who as a 19-year-old boy travelled from Barking to Victoria Park. “The whole Two Tone movement was a vindication of RAR.”

Today the British music scene is visibly diverse: note the celebration of Stormzy, Jorja Smith and Kendrick Lamar at this year’s Brit Awards. There is still a way to go but Britain has become a profoundly more multicultural country since the bad old days of the Seventies. And in some crucial way that’s down to RAR. “I think it was decisive in running the NF out of town,” says Hain now. “It helped create a climate in which being racist was not acceptable.”

Or as Tom Robinson, now a BBC6 broadcaster who will later this year perform his Power in the Darkness album at a number of gigs on the occasion of its 40th anniversary, put it: “It was our Woodstock.”

SEE ALSO: Rock Against Racism: Syd Shelton images that define an era

09 December 2018 Unite Against Fascism and Racism | Details…

09 December | No Pasaran

09 December | No Pasaran

United Against Fascism and Racism

Stop Tommy Robinson

Assemble 11am BBC Portland Place

March to Whitehall.

Timely tale of a boy who walked out of poverty, a teenager who stood up to racism, a soldier who fought fascism and an old man who inspired a new generation.

The Young’uns take The Ballad Of Johnny Longstaff on tour across the UK in January and February 2019. BOOK HERE…

From the shadow of the Teesside shipyards, to the banks of the Thames. From Cable Street to the Spanish Civil War. Johnny Longstaff bore witness to some of the most defining moments of the early 20th century. Before he died, he recorded his story in words which were harrowing, hilarious, poignant, proud and ultimately uplifting.

How the project came about

In 2015, a man arrived at one of our concerts with a picture of his late father and a story. His father’s name was Johnny Longstaff and what a story he had to tell.

As a teenager, Johnny walked 230 miles from our hometown of Stockton-On-Tees to London in search of work and from then on bore witness to some of the most defining moments of the tumultuous 1930s including the Battle of Cable Street and the Spanish Civil War.

Exploring Johnny’s story through his own spoken words with the recordings he made for the Imperial War Museum and having access to his never before published memoirs and his personal book & photo archive has been a labour of love for us.

Three years later we have created a 90 minute show in which 16 original songs interweave with Johnny’s own voice against a backdrop of startling visuals to tell an incredible story. It’s not a story that glorifies conflict or imposes political views – it’s a story that oozes humanity, humour and fellowship.

Johnny’s story

In the summer of 1939, as war clouds loomed over Europe, a 19-year old lad from Teesside went to the House of Commons to meet his local MP. He had just returned from fighting against fascism in the Spanish Civil War (to do so was illegal because of Britain’s policy of non- intervention).

Hearing footsteps coming down the corridor he turned to see the figure of Winston Churchill approaching. The lad’s MP took the opportunity of introducing him. Churchill looked the teenage soldier up and down, took his cigar out of his mouth, and said ‘Would young men like you be prepared to fight against Hitler?’ The lad took a deep breath before he answered; ‘Mr Churchill,’ he said, ‘I’ve been fighting Hitler all of my life.’

His name was Johnny Longstaff.

This is the story of his life from the day it began in abject poverty in Stockton-On-Tees in 1919 to that chance meeting with Churchill in 1939. 16 original songs interweave with the late Johnny’s own recorded voice to tell a remarkable story of one man’s impulse to react to injustice wherever and whenever he saw it.

It’s a story of great humanity but also great humour as a teenager stumbles his way innocently through the tumultuous landscapes of the 1930s – from Teesside to London, then onto Paris and eventually across the Pyrenees into Spain (even though he didn’t even know where Spain was).

16 songs

With sixteen songs the trio sing their way through Longstaff’s remarkable life. Songs like Any Bread and Carrying The Coffin recall the poverty and destitution of life in the north-east in the Great Depression, while Cable Street (see below) retells the tale of the famous battle with Moseley’s fascists on the streets of London. The Great Tomorrow, Trench Tales and David Guest recall the experiences of fighting Franco’s fascists. The show ends with The Valley Of Jarama, which was written by Alex McDade, one of the volunteers of the British Battalion fighting the fascists.

The Ballad Of Johnny Longstaff on tour

The Young’uns take The Ballad Of Johnny Longstaff on tour across the UK in January and February 2019. BOOK HERE…

The Young’uns’ latest album Strangers won the 2018 Best Album in the BBC Folk Awards. They were the winners of Best Group in both the 2015 and 2016 BBC Folk Awards.

“This Teesside trio have captured hearts – and awards – with a magic combination of lusty singing, memorable tunes and heart-on-sleeve songwriting. They are modern day troubadours of working people its a role they play with absolute commitment and huge skill.” – Songlines

Cable Street