Public Reading Rooms is very pleased to publish this interesting and informative piece from the veteran Marxist Ian Birchall . Ian’s article forms part of an important discussion about the hugely significant political developments of recent weeks. Our pages are open. Please write to us at [email protected]

A friend recently suggested to me the comparison between the current wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations and the events of 1968. For someone of my age it is an interesting comparison. Obviously I am in no position to make a properly documented historical assessment, but I have attempted to compare some aspects. I am writing largely from memory, and my perspective will necessarily be subjective and impressionistic, but I offer these somewhat disconnected thoughts as a small contribution to the current political debate.

I should begin by saying something of my own situation, which must be taken into consideration in relation to any comparisons I may make. I was slightly older than the generation radicalised by 1968; I had become active in the Nuclear Disarmament movement around 1960, and in 1962 had joined the International Socialists – forerunners of the SWP. For some five years I had been calling myself a Marxist and a revolutionary, though I was only beginning to understand the meaning of those words. In 1968 events that had seemed to belong to a hypothetical future became part of the real world. I was heavily involved in the movement of 1968 – meetings, demonstrations, etc.; looking back it is hard to imagine how I found the time for it all. Ostensibly I was joint author of a small pamphlet on the French events, though in reality I was merely Tony Cliff’s research assistant.

Today my situation is very different. I have mobility problems which mean that, even without the lockdown, I should be unable to attend meetings or demonstrations. I may respond to events with approval, even admiration, but my knowledge is limited to what is available in print and online, plus occasional discussions with comrades. And of course the present situation is only the very beginning. It is clear that the BLM movement, added to the coronavirus crisis and the increasing threat of climate change, is opening up a new historical phase. But I am unlikely to live long enough to assess what it will mean. To an observer of history like myself it is a bit like reading a detective story from which the last chapters have been torn out.

What can be said about the current wave of resistance from BLM etc. from the perspective of a one-time 1968 activist? Perhaps not much. I am not particularly well-informed, and the movement is still at a very early stage. So my observations will be tentative and cautious.

One comparison illuminates the sheer scale of events. According to no less than Priti Patel, some 137,500 people attended protests in Britain over the weekend of 6-7 June. (Guardian, 8.6.20) That is considerably in excess of the hundred thousand which were claimed for the October 1968 Vietnam demonstration – although we had no lockdown to contend with and had been working to build the demonstration for some months.

News that the Minneapolis city council has pledged to disband the city’s police department was remarkable. An ageing sceptic like myself may wonder just what it will mean and what the new arrangements will amount to, but there is no doubt that some important changes are going on.

US dockworkers on strike for Black Lives Matter

Much has been written about 1968, a good deal by historians who are too young to remember it. There is now a whole field of academic study entitled “1960s protest research”. Of course there will always be a conflict between the viewpoint of those who actually took part and those who have worked from the archives – I am always thankful, when I write about the French Revolution, that there are no surviving sans-culottes to complain “It wasn’t like that”.

The centrepiece of 1968 was the French general strike – ten million workers; still, to the best of my knowledge, the biggest general strike in human history. But illiterate journalists feel it can be dismissed as “student riots”. And 1968 led on to a series of events around the world – the massive strike wave in Italy in 1969, the humiliating defeat of the United States in Vietnam, the strike by British miners in 1974 which provoked a general election and led to the fall of the Tories, the Portuguese revolution which looked as though it might spill over into post-Franco Spain. All these events created a sense that a revolutionary perspective for the coming years was far from unrealistic. Historians with the wisdom of hindsight may assure us that the system was in no danger – but we don’t live our lives in retrospect.

In my recollection one central aspect was the sense of urgency. I remember hearing Tony Cliff in Hornsey Town Hall at the end of May 1968, arguing that capitalism and trade unions could no longer co-exist. Perhaps it would be five years, perhaps it would be seven before the final confrontation. He concluded: “If I am wrong, I see you in the concentration camps”. Cliff himself soon adjusted his over-dramatic timescale. But he was not entirely wrong. In just over five years there would be concentration camps in Chile – and internment in Northern Ireland.

Tony Cliff

One thing that should be stressed is that the question of racism was central in 1968, just as it is today. In Britain one defining political event of the year was Enoch Powell’s “rivers of blood” speech. This was an extremely alarming event, which focussed the minds of the left on the emerging threat from the racist right. And doubly alarming, especially for those of us who had been welcoming the rise in industrial militancy and opposition to the Labour government’s wage controls, was the fact of groups of workers taking strike action in support of Powell. Above all there was the strike by London dockers.

Here it is important to recall a figure often forgotten in accounts of 1968. Terry Barrett was a London docker who had joined the International Socialists and had worked closely with us around the dock strike in 1967. When the dockers voted to strike in support of Powell, Barrett gave out a leaflet – written by Paul Foot – putting a clear class position against Powell, pointing out for example that Powell had called for mass sackings on the docks. Barrett showed great courage and was totally isolated – other dockers threw coins at him. Of course he was quite unable to prevent the dockers from striking for Powell. But the fact that IS took such a firm anti-racist position helped to attract some of the people who would build the Anti-Nazi League a few years later.

In France many of the leaders of the 1968 movement had been radicalised by the colonial war in Algeria which ended in 1962. Alain Krivine, one of the most prominent student leaders, had been a member of the Communist Party youth section, but had been reprimanded for making contacts with the Algerian National Liberation Front. He had then become involved in solidarity activity with the Algerian struggle. Yvon Rocton had gone to Algeria as a conscript and had been sent to a punishment battalion for protesting at the army’s use of torture. On his return to France he had joined a Trotskyist organisation, the Parti Ouvrier Internationaliste. In 1968 he was working at the Sud-Aviation aircraft factory in Nantes, where he led a factory occupation which was to be the first in France, and would spark off a national wave of occupations over the following days.

Obviously racism is central to the current movement of struggle. I want to be very careful about how I discuss the comparison with 1968. Of course people get justifiably very angry when Tory politicians assure them that Britain is not a racist country. And it is the victims of racism who have an absolute right to define the racism they experience. Racist practices and attitudes remain deeply embedded in British society. (I shall confine my comments to Britain – I don’t know enough about the USA to comment in any depth.) Anyone who, like myself, is misguided enough to spend far too much time on Twitter is aware of the vile – and often semi-literate – racist abuse that flourishes there; whether spontaneous or centrally coordinated – probably a bit of both – it is substantial enough to be very alarming.

Yet at the same time it seems to me that it would be defeatist to suggest that nothing has changed, that fifty years of anti-racist campaigning have achieved nothing whatsoever. Doubtless we made mistakes, doubtless we sometimes did not try hard enough. But if nothing has changed, it would seem to imply that campaigning is futile.

My own feeling is that racism in Britain, though still very real, is more on the defensive than it was fifty years ago. I remember how overt racism was in the 1960s. Until just before 1968 it was still legal to advertise a room to let with the words “No Blacks” (or an appalling example, for its mixture of racism and snobbery, “No Blacks except embassy”). South African apartheid was widely defended. Those who opposed sporting links with South Africa were accused of bringing “politics” into sport. Today it would be hard to find a Tory MP who would express other than admiration for Nelson Mandela. But back in 1964 those of us (including myself, Tariq Ali and several others still active on the left today) who demonstrated vigorously against the South African ambassador after Mandela was jailed were a tiny minority and widely reviled.

That racism was equally deeply established in the Labour Party. I remember we raised in our local branch the question of a colour bar in a local Labour Club – and one member quite cheerfully telling us they didn’t want blacks – or Jews! In the 1964 election I was leafleting a polling station with a Labour Party member. He gave a leaflet to a black voter, saying (clearly with no concern as to whether he could be heard) “if you can read”.

Now when people in positions of power and authority are challenged about racism, they are somewhat more defensive, more apologetic, more anxious to insist that they are opposed to racism. And attitudes are changing. As Richard Evans points out in the New Statesman (19-6-20) a poll in 2014 showed that 59 per cent of UK respondents thought the British Empire was something to be proud of. By March this year the figure had fallen to 32 per cent.

I belong to the generation that grew up when the empire was taken for granted. Like many homes mine had a map on the wall showing the British Empire in red. As a child I was made to collect money for missionaries – the benighted populations outside Europe had false religions and had to be given the true one. I doubt if those of us who grew up in that world of empire will ever totally shake off its legacy – but we are dying off fast.

There is a long, long way to go, but we have made some progress and we need to go on pushing. But of course I realise that for someone young and angry being told that things were even worse fifty years ago isn’t a lot of consolation.

So it is important to analyse the various forms which racism takes. Is Boris Johnson a racist? Inasmuch as he is quite happy to make irresponsible use of racial stereotypes in order to achieve journalistic effect, yes. He has the typical arrogance of a privileged white upper-class Brit. But does he have a political strategy based on racist principles? Unlikely, since he wouldn’t know a principle if one ran up his trouser leg. Johnson attacked Muslims and single mothers because he knew it would confirm the vile prejudices of readers of the Spectator and Telegraph. He would praise Stalin if there was money in it.

In 1968 we saw racism as deeply rooted in capitalism, so that the struggle against racism feeds directly into a broader struggle against capitalism. The same seems to be true for many of today’s militants. Socialist Worker (17.6.20) quite rightly quotes with approval Angela Davies’ statement that “the only true path of liberation for black people is the one that leads towards a complete and total overthrow of the capitalist class” – though I suspect the interrelation of the struggles may be more complex than some of Socialist Worker’s simplistic formulations. But at least its positions are more credible than the Weekly Worker’s remarkably complacent claim (11.6.20) that “in western capitalist societies…. deliberate efforts have been made to diversify the professional layers of society over many decades”, and that therefore anti-racism can be dismissed as mere “identity politics”.

1968 must be seen in its historical context. It came towards the end of what is often called the “long boom”, the period of twenty-five years or so after World War II when Western capitalism enjoyed economic expansion and full employment. For many, in the labour movement and elsewhere, it seemed that capitalism had changed for good, that prosperity and full employment would last for ever. The IS held a position known as the “permanent arms economy”, based on the work of Michael Kidron, which argued that the long boom was based on massive arms spending. The mechanisms whereby this happened were complex and open to question (Kidron himself later moved away from the theory), and few of us understood them properly, but the conclusion was simple – the boom was real (as against those on the far left who continued to promise imminent slump) but it would not last for ever and it was bought at the very real price of the danger of nuclear war. As to how long the boom would last and what would happen when it ended, we were rather vague.

The long boom had produced a working class that was strong and self-confident. When its situation began to be undermined as the boom came to an end, it initially fought back with great vigour. The peak year was 1972, when engineers joined miners at the Saltley picket and won the strike; a few months later five dockers were jailed for breaking anti-union laws. As strikes spread, the state was obliged to invoke an obscure legal figure (the Official Solicitor, who pleaded on behalf of children and others unable to defend themselves) to get them out. I remember seeing the release in a pub in Hull, and thinking, in a way I have never done before or since, “Our side has won”.

It didn’t last. By the end of the seventies the militancy had run out of steam. Tony Cliff argued that there had been a “downturn” in struggle. In the short term he was right and saved IS from many of the problems that beset other organisations confronted with a setback to their militant aspirations. In the longer term he was wrong. Cliff and we in the SWP expected the “downturn” to be short-lived and to be followed by a renewal of struggle. We’re still waiting. The lesson, I think, is that there is no automatic relation between economic crisis and resistance.

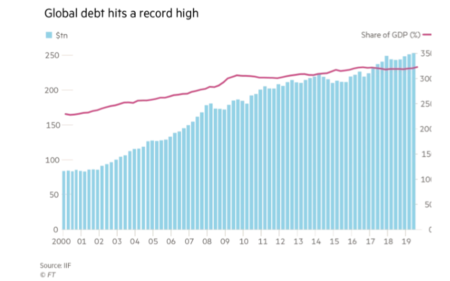

It is clear that the impact of coronavirus will be to produce an international economic crisis. The depth and extent of that crisis is unpredictable. Even more unpredictable is what will be the effect on class consciousness and movements of resistance. Will threats to living standards provoke militant resistance, as they did in 1972, or will rising unemployment intimidate and subdue workers, as it did in the later 1970s? It’s too soon to know.

In the ten years preceding 1968 France had been ruled by General de Gaulle. He was an autocrat, with a carefully designed presidential system that enabled him to exercise power. He was eccentric, rather quaintly old-fashioned, but certainly not a fascist. The left had failed to remove him electorally. In 1968 he put an end to the movement by calling an election; a frightened middle class flocked to vote for him, while a working class that had seemed to be on the brink of achieving much more showed no enthusiasm for the left. But de Gaulle’s triumph was short-lived. The following year he called a referendum and was quietly but effectively stabbed in the back by his own allies. 1968 had, after a short delay, put an end to de Gaulle. I would not want to take a comparison between de Gaulle and Trump too far; but perhaps there are parallels with the way Trump’s support among his own allies is beginning to slip away as he fails to deal with either coronavirus or the BLM revolt.

In 1968 de Gaulle won the support of army leaders. But in the end he did not use the army against the strike movement. France still had a conscript army. Many soldiers had been, or aspired to be, students. And almost every soldier must have had a striker in his family or his close circle of friends. Could the army have been relied on if it had been asked to confront strikers? De Gaulle had the spectacle of Vietnam, where the US army was increasingly unwilling to fight an unjust and unsuccessful racist war, and where many black soldiers sympathised with the black revolt back in the US. Today the US is still haunted by Vietnam; whatever its military needs it dare not bring back the draft. And now Trump’s threats to use the army against protesters has led to open dissent from military leaders. Lenin’s view of the state (“special bodies of armed men”) remains valid, but contradictions within the state are becoming more visible.

Another important question is that of fascism. When fascism first emerged in the 1920s it it caused a lot of difficulties for Marxists, who tended to see it in terms of reactionary movements from the past rather than recognising a new and very dangerous phenomenon. (The Italian Communist Party used to refer to Mussolini’s blackshirts as “white guards”, which must have caused considerable confusion.) A bit later the irresponsible use of the term fascist – in particular the description of social democrats as “social fascists” – played a significant part in enabling Hitler to take power.

But since 1945 the term “fascist” has often been used indiscriminately and confusingly. The IS appeal for left unity in 1968 was entitled “The Urgent Challenge of Fascism”. It was misleading. The threat of racism was real and immediate. Over the coming few years small but pernicious fascist organisations would emerge, but the main threat to the working class, black and white, came from mainstream parties – Labour as well as Tories.

Today the enemy is different. There are real fascists – and at times it is necessary to expose and confront them. But they are not the main enemy. Donald Trump has some reactionary, evil and dangerous policies – but he is not a fascist. Marxist analysis of new forms of reactionary rule, not mere sloganising, is required.

An important fact about the French general strike, often neglected, is that out of ten million strikers, at best three million were union members. Unionisation levels in France were very low – partly as an inheritance of the syndicalist view that unions were the organisation of the “active minority” rather than of the totality of wage-earners, and partly because of the divisions in French trade-unionism, with three main federations, under Communist, social-democratic and secularised ex-Catholic leaderships.

The low level of unionisation was a great asset for the Communist Party and the union it controlled, the CGT. Where they were dominant, the factory occupations were run by union activists, while the non-unionised were sent home to watch the state-controlled television. The Trotskyists of Lutte ouvrière argued that revolutionaries should present a programme for non-unionised workers. British comrades, used to near-100% unionisation levels, tended to be rather scornful of this, saying that the only message for non-union members was “join the union”. Presumably they imagined that revolutionaries should spend their time during a general strike filling in membership forms and putting them in the post (….. oh! the postal workers were on strike).

The point is not to argue against working in the unions. The role of the unions was crucial in controlling the strike and getting workers back to work, and it was vital to be in the unions to counter this. But it was also important to recognise that the majority of workers were not in the unions, and to find ways of addressing them and involving them actively in the movement. Similar flexibility will be required in the future.

The development of communications has been an important factor. Vietnam – and with it the international wave of opposition to the US aggression – was the first war to be widely followed on television. But in other ways things were very different to today. Telephones existed – but they were firmly rooted in houses. The idea of putting one in your pocket was pure science fiction. I remember being in Paris in the 1970s and to phone London I had to go to a post office and get an operator to connect me.

So there were plenty of rumours. I remember hearing in the course of the May events that demonstrators had burned down the Paris Stock Exchange. Naturally we thought this was rather a good thing. When I finally got to Paris in July I made a point of going to the Stock Exchange. I walked right round the building and could not find so much as a single scorch mark.

From the age of Twitter communication in 1968 looks almost unbelievably sluggish. So it is no surprise that the BLM movement has spread to so many countries so rapidly. Within a week of the first demonstrations in the USA the movement had spread to Mexico, Brazil, Britain, France, Germany, Denmark, Italy, Ireland, New Zealand, Poland, Israel and Canada. (“Ten Days That Shook the World”, RS21, 4. 6. 20) More than ever before capitalism is an international system and resistance must be international too.

1968 was a year – like 1848 and the aftermath of 1917 – when revolutionary ideas spread rapidly across frontiers. Often those of us who challenged the Stalinist theory of “socialism in one country” had been accused of advocating “simultaneous revolution”. But in 1968 the idea did not seem quite so absurd.

The far left had to respond, very quickly, to the challenges of 1968. I’ll focus on the International Socialists, as that was where I was.

How can the Marxist left today relate to the emerging movement? We have to begin from where we are. The Marxist left in Britain today is lamentably small and divided. The biggest organisation is probably the SWP, with in reality no more than a thousand members and a paper sale of at best three thousand. The SWP used to claim to “punch above its weight”, but I doubt if it does any more. The simple fact is that, after fifty years of “building the party”, the Marxist left in Britain is much smaller and less influential than it was in 1968.

In 1968 the Marxist left in Britain had the prospect of rapid growth – in 1968 IS more than doubled its membership (450 to 1000). Those new members were mainly young, enthusiastic and hyperactive. There is no similar prospect today.

For many years I believed the SWP offered the possibility of an organisation which combined what was best in classic Marxism-Leninism-Trotskyism with a realistic assessment of current reality. (As Tony Cliff used to say: “If you sit on Marx’s shoulders you see far, but if you sit on Marx’s shoulders and close your eyes, you don’t see very far at all”.) In 2013 I, and many other comrades, were painfully obliged to acknowledge that we had been wrong – an organisation which couldn’t deal with a rogue National Secretary was hardly likely to stand up to the bourgeois state. For a little while there was perhaps a glimmer of hope that the International Socialist Organization in the USA could achieve the required synthesis, but that has now liquidated itself.

The IS response in 1968 was a return to Leninism. After two stormy conferences a “democratic centralist” constitution was adopted. Cliff began to lecture on Lenin and started writing his four-volume biography. It was not an unreasonable position. A more effective, interventionist organisation was needed for the period that was opening up. Lenin’s Bolshevik party was the only model we’d got, hopefully interpreted in not too literal or mechanical a way.

It seemed to make sense in historical terms. 1917 had opened up a period of revolutionary change, but this had been driven off course by the rise of Stalinism. Now, we thought, the Stalinist detour was over. The French Communist Party’s sluggish and conservative response to the strike wave, and the international crisis of Communism caused by the invasion of Czechoslovakia, marked the beginning of the end of Moscow’s domination of the international left. As Tony Cliff used to say – there is now no danger of the left capitulating to Stalinism – they are moving rightwards so fast you can’t catch up with them to capitulate. So, apparently, we could resume the natural course of history from where we had been interrupted in the mid-twenties.

Today it is clear that, whatever we can aspire to in the future, it is not a rerun of 1917. Of course it is still worth studying 1917, as one historical topic among others; there are always lessons to be learned and inspiration to be gained. Lenin still repays study, among other things for his theory of the state, for his remarkable flexibility about organisational forms as objective circumstances changed, and for his wonderfully agnostic final speech to the Comintern in 1922: “The resolution is too Russian, it reflects Russian experience. ….. Nothing will be achieved that way. They must assimilate part of the Russian experience. Just how that will be done, I do not know.”

In a period of rising struggle organisation is certainly required. Nothing happens spontaneously, there is always someone who takes a lead or proposes an initiative. In 1968 we turned to Leninism because it seemed the best thing going. Now there is no obvious model for organisation. So there will undoubtedly be heated debates about organisational forms. In the period just before the coronavirus Extinction Rebellion drew in more activists in a few months than the Marxist left had done in twenty years. This is not to say that XR has solved the problem of organisation; undoubtedly its members will recognise weaknesses and learn from mistakes. There are no models from the past, from 1917 or 1968, which will solve our problems.

The far left in 1968 was small and fragmented. (Until 1968 the largest British Trotskyist organisation had been the Socialist Labour League, which in October 1968 gave out leaflets boasting that it was not taking part in the Vietnam demonstration. IS overtook it in 1968.) IS put out an appeal for left unity on the basis of a minimum programme. This was mainly aimed at the International Marxist Group (IMG). This had “orthodox” Trotskyist politics and until recently had been oriented to the Labour left, but it had done excellent work in building the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. And it had Tariq Ali. Tariq was a formidable orator – I remember hearing him at the Friends’ Meeting House just after he had returned from Vietnam. He had to plead with the audience to stop clapping so that he could get on with his speech. And, although he was no longer a student, he had been built up by the press as a “student leader”. IS plus Tariq could have created a powerful pole of attraction to establish a left organisation of several thousands. (How long it would have lasted after the euphoria of 1968 had worn off is a different question.) It nearly happened – as Ernie Tate has shown in his autobiography (Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s & 60s, 2014) the IMG was divided and might well have agreed to a fusion. Instead IS fused with a small group around Sean Matgamna, which produced three years of internal conflict, and gave the SWP a phobia about factional rights which has lasted half a century.

So what remains? The left unity initiative, which failed in 1968, would now be completely futile. Dragging the tired, depleted fragments of the Marxist left together would achieve nothing – in fifty years we have just acquired more reasons to bear grudges again each other. And, it seems to me, the whole Leninist project is now exhausted. When the USSR collapsed in the early 1990s we hoped it would mean a revival of the “genuine” Marxist left. It didn’t happen. Tony Cliff’s claim (Trotskyism After Trotsky, 1999) that Trotskyism was “coming into its own” again was no more than wishful thinking.

What we need to address is something which blighted all attempts at left unity in 1968, and remains a huge obstacle today. It is what Peter Sedgwick referred to as the idea of the “apostolic succession”, the belief that one particular organisation is the true heir of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky, and has a monopoly of “correct” positions. All other organisations are dismissed as counter-revolutionary, or at best as irrelevant sects. I am more sympathetic to the idea expressed by Tony Cliff in his magnificent lecture on Engels, only five years before his death: “ideas are like a river and a river is formed from lots of streams”.

In 1968 Trotskyists, Maoists and anarchists cooperated briefly, before their differences began to harden. In 1968 some of us in IS cooperated with Black Dwarf, as well as helping to launch the weekly Socialist Worker, believing the two publications could be complementary. Alas, we were soon at each other’s throats.

Today it seems to me that a range of publications – journals and websites – can coexist, helping to develop and propagate Marxist ideas. Jacobin, Catalyst, Salvage, RS21, Historical Materialism, Spectre, Tribune, New Left Review – and many more I’ve probably never heard of, have a role to play. Party publications can contribute as well, if they abandon the claim to a monopoly of truth.

Until 1968 the IS worked inside the Labour Party. This was not “entrism” in the classic sense – it simply provided a milieu where we could meet and discuss with other people of left-wing views. In the early 1960s the tactic paid off – IS membership quadrupled (50 to 200) from work in the LP Young Socialists. (Whether such recruitment ever works except in youth organisations I don’t know – I suspect not). But in the mid-sixties the emphasis was shifting – we were more involved in industrial struggles and tenants’ campaigns, and less in internal arguments in the LP. In 1967 I tried quite hard to get myself expelled, but the LP was too gutless to throw me out.

The Wilson government from 1964 had been a great disappointment even to those of us who had not expected very much of it. Wilson froze wages, tightened immigration controls and backed the US in Vietnam. The response to the Powell speech was abject – for a fortnight after the speech Wilson and the other Labour leaders remained silent; Powell’s slanders went unanswered. 1968 was the end of the road – most comrades left the LP, though a few stayed in where local parties offered a favourable environment. In 1970 there was a fierce internal debate before we even decided to call for a Labour vote.

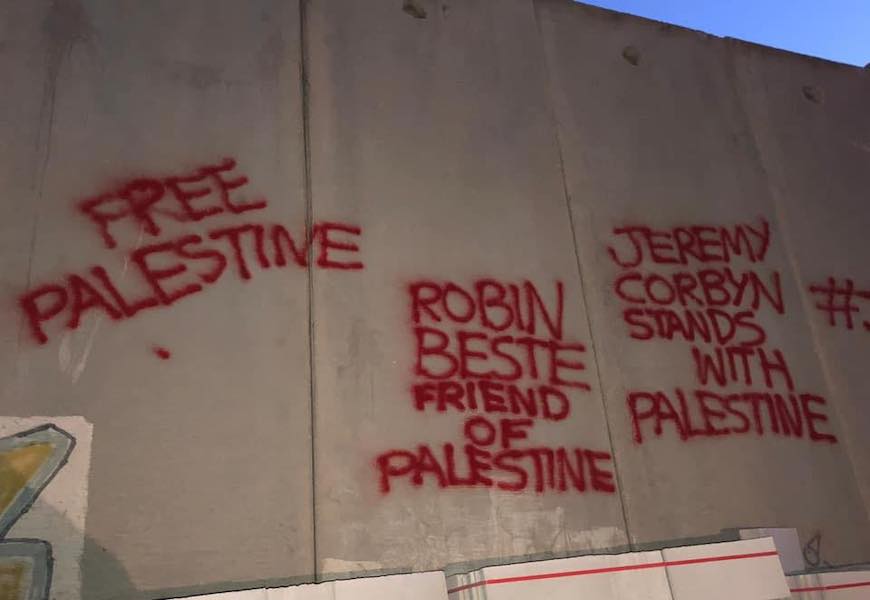

Were we wrong, premature in our departure? In my view the whole Corbyn experience has proved that it is impossible to take over the Labour Party from the top down. But I understand why individuals would want to go into the Labour Party, if they think it is a useful milieu for meeting and discussing with other left-wingers. A publication can address those inside and outside the Labour Party, and encourage dialogue between them. An organisation which requires all its members to be inside or outside the Labour Party merely aggravates the problem.

One of the lessons of 1968 was the need for flexibility in terms of tactics and organisation. There was a student occupation at Hornsey College of Art. One morning I was phoned to be told that security guards with dogs had gone in to clear the students out. I set off for Hornsey, unsure what sort of a confrontation lay ahead. By the time I got there the students had “fraternised” – they were offering cups of tea to the security men and feeding biscuits to the dogs. In the nuclear disarmament movement I had often argued against those who made “non-violence” a principle – here it worked perfectly as a tactic.

When I came into politics, about eight years before 1968, Marxism was pretty thin on the ground. Certainly the writings of Marx and Lenin were easily available in cheap editions produced in Moscow. But only two or three books by Trotsky were available. Luxemburg was almost unknown until a couple of books by Tony Cliff and JP Nettl appeared. Gramsci was virtually unknown, and Lukács was represented only by a couple of volumes of rather Stalinist literary criticism.

1968 led to a boom in left publishing. Much classic Marxist material became available again, and there was a flood of new books. For a while in the 1970s and 1980s Marxism was almost fashionable in academic circles. It would be wrong to claim that nothing of value was produced, but in a great deal of work the link between theory and practice often seemed tenuous.

Today, above all with the Marxist Internet Archive, as well as publishing initiatives like Historical Materialism, there is no problem about the availability of Marxist literature. The question of how it feeds into the problems and needs of a real movement is a very different matter. In 1968 Marxists began to attract a small audience because what they were saying seemed to fit the way history was moving. Likewise Marxists today can have a real influence on the movement if they offer analyses which are convincing and fit the complexity of the situation.

One small sign of hope is the way Marxism remains a target for the apologists of the right. BLM is absurdly accused of being a “Marxist” organisation, and the accusation of “cultural Marxism” is thrown around, generally by those equally ignorant of Marxism and of culture. Hopefully all this will awaken an interest in Marxism among at least a few young people. (I first heard of Trotskyism as a result of the witch-hunt of the South Bank building workers’ strike in 1958.)

One final observation on 1968. It is only a personal impression, and in recent years often based on attendance at funerals. But I am struck by how many of those whom I knew in the years before and after 1968 remained active in left politics. Of course there have been many splits and divisions, and old comrades have chosen different paths. Many have devoted themselves to specific issues and campaigns rather than generalised revolutionary politics. There have been renegades, like the Hitchens brothers, but only very few. Nonetheless I think it is true that the experience of 1968 radicalised a generation of activists who have remained involved, in one way or another, in the left for over half a century. It seems likely that in fifty years time – if human civilisation survives that long – ageing activists will recall how they were first radicalised by the demonstrations of 2020.

That something very significant is now happening is not in question. How it will develop, what forms of organisation and activity will endure or be modified, is quite unpredictable. There are still some very nasty reactionaries at every level of society, and they will not surrender easily. But real gains can be made, and a new generation of activists is emerging. Will there be echoes of 1968? Today’s world is very different from 1968, in its hopes and dangers, but in Victor Serge’s words the left of the future will be “infinitely different from us, infinitely like us”.

Ian Birchall

June 2020

]]>

”

”

]]>

]]>