Regardless of Castillo presidency’s evident shortcomings and mistakes, his ouster represents a grave setback for democracy in Peru and Latin America as a whole. His election last year took place on the back of an almighty crisis of credibility and legitimacy of a political system rigged with corruption and venality in which presidents were forced to resign on corruption charges (some ended in prison), with one committing suicide before being arrested on corruption charges. In the last six years Peru has had six presidents.

The rot was so advanced that no mainstream political party or politician could muster sufficient electoral support to succeed in winning the presidency in 2021 (the main right-wing party, Fuerza Popular’s candidate got less than 14% of the vote in the first round). It goes a long way to explain why an unknown rural primary school teacher from the remote Andean indigenous area of Cajamarca, Pedro Castillo, would become the 63rd president of Peru. In Cajamarca, Castillo obtained up to 72% of the popular vote.

Castillo’s election offered a historic chance to bury Peruvian neoliberalism. I myself penned an article with that prognosis, which I premised on Castillo’s commitment to democratize Peruvian politics via a Constituent Assembly tasked with drafting a new constitution as the base from which to re-found the nation on an anti-neoliberal basis. A proposal that, in the light of recent experience in Latin America, is perfectly implementable but whose precondition, as other experiences in the region have shown, is the vigorous mobilization of the mass of the people, the working class, the peasantry, the urban poor, and all other subordinate strata from society. This did not happen in Peru under Castillo’s presidency.

Ironically, the mass mobilizations that broke out in the Andean regions and in many other areas and cities in Peru when they learned of Castillo’s impeachment solidly confirms that this was the only possible route to implement his programme of change. The mass mobilizations throughout the nation (including Lima) are demanding a Constituent Assembly, the closure of the existing Congress, the liberation, and reinstatement of Castillo to the presidency, and the holding of immediate general elections.

This would explain the paradox that right-wing hostility to president Castillo, unlike other left governments in Latin America, was not waged because Castillo was undertaking any radical government action. In fact, opposition to his government was so blindingly intense that almost every initiative, no matter how trivial or uncontroversial, was met with ferocious rejection by Peru’s right-wing dominated Congress. The Congress’ key right-wing party, was Fuerza Popular led by Keiko Fujimori, daughter of Peru’s former dictator, Alberto Fujimori. In Peru’s Congress of 130 seats, Castillo counted on 15, originally solid, votes from Peru Libre, and 5, not very solid, votes from Juntos por el Peru. In the absence of government mobilization of the masses, the oligarchy knew Castillo represented no threat, thus their intense hostility was to treat his government as an abhorrent abnormality sending a message to the nation that it should never have happened and that would never recur.

One example of parliament’s obtuse obstructionism was the impeachment of his minister of foreign relations, Hector Béjar, a well reputed left-wing academic and intellectual on 17th August 2021, who, barely 15 days after his appointment and less than a month after Castillo’s inauguration (28th July 2021), was forced to resign. Béjar’s ‘offence’, a statement made at a public conference in February 2020 during the election – before his ministerial appointment – in which he asserted a historical fact: terrorism was begun by Peru’s Navy in 1974 well before the appearance of the Shining Path [1980]. Béjar was the first minister out of many to be arbitrarily impeached by Congress.

Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), an extreme guerrilla group, was active in substantial parts of the countryside during the 1980s-1990s and whose confrontation with state military forces led to a generalised situation of conflict. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission that, after the collapse of the Fujimori dictatorship, investigated the atrocities perpetrated during the state war against the Shining Path, reported that 69,280 people died or disappeared between 1980 and 2000.

Congress’ harassment aimed at preventing Castillo’s government from even functioning can be verified with numbers: in the 495 days he lasted in office, Castillo was forced to appoint a total of 78 ministers. Invariably, appointed ministers as in the case of Béjar, would be subjected to ferocious attack by the media and the Establishment (in Béjar’s case, by the Navy itself) and by the right-wing parliamentary majority that was forcing ministers’ resignation with the eagerness of zealous witch hunters.

Béjar was ostensibly impeached for his accurate commentary about the Navy’s activities in the 1970s but more likely for having made the decision for Peru to abandon the Lima Group, adopting a non-interventionist foreign policy towards Venezuela and for condemning unilateral sanctions against nations. Béjar made the announcement of the new policy on 3rd August 2021 and the ‘revelations’ about his Navy commentary were made on August 15th. The demonization campaign was in full swing immediately after that which included: soldiers holding public rallies demanding his resignation, a parliamentary motion from a coalition of parliamentary forces essentially for ‘not being fit for the post’, and for adhering to a ‘communist ideology.’

Something similar but not identical happened with Béjar’s replacement, Oscar Maurtúa, a career diplomat, who had served as minister of foreign relations in several previous right-wing governments from 2005. When in October 2021, Guido Bellido, a radical member of Peru Libre, who upon being appointed Minister of Government, threatened the nationalisation of Camisea gas, an operation run by multinational capital, for refusing to renegotiate its profits in favour of the Peruvian state, Maurtúa resigned two weeks later. Guido Bellido himself, was forced to resign ostensibly for an “apologia of terrorism” but in reality for having had the audacity to threaten to nationalise an asset that ought to belong to Peru.

On 6th October 2021, Guido Bellido, a national leader of Peru Libre, who had been Castillo’s Minister of Government since 29 July, offered his resignation at the president’s request triggered by his nationalization threat. Vladimir Cerrón, Peru Libre’s key national leader followed suit by publicly breaking with Castillo on 16th October, asking him to leave the party and thus leaving Castillo without the party’s parliamentary support. Ever since, Peru Libre has suffered several divisions.

Worse, Castillo was pushed into a corner by being forced to select ministers to the liking of the right-wing parliamentary majority to avoid them not being approved. All took place within a context dominated by intoxicating media demonization, accusations, fake news and generalised hostility to his government but with a Damocles sword – a motion to declare his presidency “vacant” and thus be impeached – hanging over his head.

The first attempt was in November 2021 (a few weeks after Bellido’s forced resignation). It did not gather sufficient parliamentary support (46 against 76, 4 abstentions). The second was in March 2022 with the charge of ‘permanent moral incapacity’, which got 55 votes (54 against and 19 abstentions) but failed because procedurally 87 votes were required. And finally, on 1st December 2022, Congress voted in favour of initiating a process to declare ‘vacancy’ against Castillo for “permanent moral incapacity.” This time, the right wing had managed to gather 73 votes (32 against and 6 abstentions). The motion of well over 100 pages, included at least six ‘parliamentary investigations’ for allegedly ‘leading a criminal organization’, for traffic of influences, for obstruction of justice, for treason (in an interview Castillo broached the possibility of offering Bolivia access to the sea through Peruvian territory), and even, for ‘plagiarising’ his MA thesis.

By then Castillo was incredibly isolated surrounded by the rarefied, putrid and feverish Lima political establishment that were as a pack of hungry wolves that had scented blood: Castillo would have to face a final hearing set by Peru’s congressional majority on 7th December. On the same day, in an event surrounded by confusion – maliciously depicted by the world mainstream media as a coup d’état – the president went on national TV to announce his decision to dissolve Congress temporarily, establish an exceptional emergency government and, the holding of elections to elect a new Congress with Constituent Assembly powers within nine months. US ambassador in Lima, Lisa D. Kenna, immediately reacted on that very day with a note stressing the US ‘rejects any unconstitutional act by president Castillo to prevent Congress to fulfil its mandate.’ The Congress’ ‘mandate’ was to impeach president Castillo.

We know the rest of the story: Congress on the same day carried the ‘vacancy’ motion by 101 votes, Castillo was arrested, and Dina Boluarte has been sworn in as interim president. Declaring the dissolution of the Congress may not have been the most skilful tactical move Castillo made but he put the limelight on the key institution that obstinately obstructed the possibility of socio-economic progress that Castillo’s presidency represented.

Castillo had no support whatsoever among the economic or political elite, the judiciary, the state bureaucracy, the police or the armed forces, or the mainstream media. He was politically right in calling for the dissolution of the obstruction of Congress to allow for the mass of the people through the ballot box to be given the chance to democratically remove it. An Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (IEP in its Spanish acronym) survey in November showed the rate of disapproval of Congress to be 86%, up 5 points from October, and staying on 75-78% throughout the second half 2021.

What was not expected with Castillo’s impeachment was the vigorous outburst of social mobilization throughout Peru. Its epicentre was in the Peruvian ‘sierra’, the indigenous hinterlands where Castillo got most of his electoral support, but also in key cities, including Lima. The demands raised by the mass movement are for the reinstatement of Castillo, dissolution of Congress, the resignation of Boluarte, the holding of immediate parliamentary elections and, a new constitution. Demonstrators, expressing their fury in Lima, carried placards declaring “Congress is a den of rats”.

In light of the huge mass mobilizations one inevitably wonders why was this not unleashed before, say, one and a half year ago? Castillo, heavily isolated and under almighty pressure, hoping to buy some breathing space, sought to ingratiate himself with the national and international right by, for example, appointing a neoliberal economist, Julio Valverde, in charge of the Central Bank, tried to get closer to the deadly Organization of American States, met Bolsonaro in Brazil and, distanced himself from Venezuela. To no avail, the elite demanded ever more concessions but would never be satisfied no matter how many Castillo made.

The repression unleashed against the popular mobilizations has been swift and brutal but ineffective. Reports talk of at least eighteen people killed by bullets from the police and more than a hundred injured, yet mobilizations and marches have grown and spread further. Though the ‘interim government’ has already banned demonstrations, they have continued. Three days ago they occupied the Andahuaylas airport; an indefinite strike has been declared in Cusco; in Apurimac, school lessons have been suspended; plus a multiple blockading of motorways in many points in the country. It is evident the political atmosphere in Peru was already pretty charged and these social energies were dormant but waiting to be awaken.

Though it is premature to draw too many conclusions about what this popular resistance might bring about, it is clear that the oligarchy miscalculated what it expected the outcome of Castillo’s ouster would be: the crushing defeat of this attempt, however timid, of the lower classes, especially cholos (pejorative name for indigenous people in Peru), to change the status quo. Peru’s oligarchy found it intolerable that a cholo, Castillo, was the country’s president and even less that he dared to threaten to enlist the mass of the people to actively participate in a Constituent Assembly entrusted with drafting a new constitution.

The appointed interim president, Dina Boluarte, feeling the pressure of the mass mobilization announced a proposal to hold ‘anticipated elections’ in 2024 instead of 2026, the date of the end of Castillo’s official mandate. However, it has been reported that Castillo sent a message to the people encouraging them to fight for a Constituent Assembly and not fall into the ‘dirty trap of new elections.” Through one of his lawyers, Dr Ronald Atencio, Castillo communicated that his detention was illegal and arbitrary with his constitutional rights being violated, that he is the subject of political persecution, which threatens to turn him into a political prisoner, that he has no intention of seeking asylum, and that he is fully aware of the mobilizations throughout the country and the demands for his freedom.

We’ll see how things develop from here. Castillo’s ouster is a negative development; it is a setback for the left in Peru and for democracy in Latin America. Latin America’s left presidents have understood this and condemned the parliamentary coup against democratically elected president Pedro Castillo. Among the presidents condemning the coup are, Cuba’s Miguel Diaz-Canel, Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro, Honduras’ Xiomara Castro, Argentina’s Fernandez, Colombia’s Petro, Mexico’s Lopez Obrador, and Bolivia’s Arce.

More dramatically, the presidents of Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, and Bolivia issued a joint communiqué (12th December) demanding Castillo’s reinstatement that in its relevant part reads, “It is not news to the world that President Castillo Terrones, from the day of his election, was the victim of anti-democratic harassment […] Our governments call on all actors involved in the above process to prioritise the will of the people as expressed at the ballot box. This is the way to interpret the scope and meaning of the notion of democracy as enshrined in the Inter-American Human Rights System. We urge those who make up the institutions to refrain from reversing the popular will expressed through free suffrage.” (my translation)

At the XIII ALBA-TCP summit held in Havana on December 15th, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Dominica, Antigua and Barbuda, St. Vincent and the Grenadines; Saint Lucía, St. Kitts and Nevis, Grenada and Cuba condemned the detention of president Pedro Castillo which they characterised as a coup d’etat.

It is very doubtful that Peru’s oligarchy will be able to bring political stability to the country. Since 2016 the country has had 6 presidents, none of whom has completed their mandate, and the impeachment of Castillo has let the genie (militant mass mobilizations) out of the bottle and it looks pretty unlikely they will be able to put it back. The illegitimate government of Boluarte has on 14th December declared a state of emergency throughout the national territory and, ominously, placed the armed forces in charge of securing law and order. The armed forces, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that investigated the dirty war between the Peruvian state and the Shining Path guerrillas (1980-1992), were responsible for about 50 per cent of the 70,000 deaths the war cost. It is the typical but worst possible action that Peru’s oligarchy can undertake.

The demands of the mass movement must be met: immediate and unconditional freedom of president Castillo, the immediate holding of elections for a Constituent Assembly for a new anti- neoliberal constitution, and for the immediate cessation of the brutal repression by sending the armed forces back to their barracks.

]]>Mendes is right; since 2 October (the date Lula won the first round with 48%), the defeated Jair Bolsonaro and his supporters have spewed a huge amount of fake news against the PT presidential candidate and his supporters. They have spread a message of hatred against not only Lula but anybody who questions or objects to it, with Bolsonaro leading by example while persistently violating existing electoral norms and rules. The violence and intimidation he has promoted has resulted in an increasingly tense atmosphere—which is liable to reach boiling point ahead of today’s second round.

Dirty Campaign

Bolsonaro’s dirty electoral campaign has been its most stark in the context of the gross abuse of his position to favour his candidacy. His expansion of increasing welfare payments in the months leading up to the first round through a special budgetary provision, popularly known as the ‘secret budget’, was deemed a scandalous sidestepping of existing constitutional norms.

And Bolsonaro’s election campaign has so intoxicated Brazil’s political atmosphere with fake news that on 18 October the Federal Police (FP) submitted a report to the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE in its Portuguese abbreviation) that bolsonarista social networks were ‘diminishing the frontier between truth and lie’. The FP’s report states that in the dissemination of false news about electronic voting in Brazil, Bolsonaro’s sons, Flavio (a senator), Eduardo (an MP), and Carlos (a local councillor), plus several key parliamentarians and members of his party, are directly involved.

The defamation of Lula has, of course, been a favourite subject. On 11 and 17 October, there were TV spots falsely accusing the ex president of being associated with organised crime. Of these, 164 were so decontextualized and so offensive that the TSE granted Lula the right to directly respond to them. The Rio de Janeiro Court Justice judge, Luciana de Oliveira, ordered on 19 October the withdrawal of two Facebook and Twitter posts insinuating Lula had shown paedophilic behaviour during an electoral visit to the Complexo Alemão neighbourhood in Rio de Janeiro the week prior.

The electoral authorities have sought to clamp down on the campaign of disinformation—including its claims that Lula practices Satanism, is engaged in narco trafficking, and suffers from alcoholism. An audio recording of a supposed conversation between two leaders of the PCC (one of the largest gangs in Brazil) about Lula being a better president for organised crime was widely circulated in Bolsonaro’s social media platforms; then, on 21 October, the same networks circulated an photo of a public meeting between Lula and Andre Ceciliano MP, who was substituted with narco trafficker Celsinho da Vila Vintem.

A video used in bolsonarista social networks also showed writer Marilena Chaui grabbing a bottle from Lula’s hands during a public event at the University of Sao Paulo in August, which went viral, along with allegations that the ex-president was drunk. In reality, Reuters Fact Check shows Lula was trying to open a bottle of water while holding a microphone at the same time, so Chaui took it from his hand, opened it, and gave it back to him.

The smear of alcoholism does not end there: a bolsonarista candidate for Congress in Parana, Ogier Buchi, formally requested in September that the TSE bar Lula from presidential candidacy on the grounds of alcoholism, for which he demanded the ex-president be tested. The TSE denied the request.

Incitement to Violence

While facilitating these lies, more seriously, President Bolsonaro has made it easy for civilians to purchase all types of guns, leading to the acquisition of thousands of weapons by his supporters. In nearly four years, Bolsonaro has issued a total of 42 legal instruments regarding the acquisition of firearms. Almost all of these presidential decisions were published in the quiet of the night, and in night editions of the Official Gazette (on many occasions on the eve of bank holidays to minimise publicity).

Rio de Janeiro, a city of 16 million, is where the connection between armed gangs and right wing politics is at its strongest, with militarised groups, drug traffickers, and evangelical churches dominating most of the poor areas. Bolsonaro won against Lula in the first round in nine out the ten of the Rio areas controlled by militias. The PT’s Rio de Janeiro Councillor, Taina de Paula, pointed out that the activists campaigning for Bolsonaro operate in these areas while most other campaigners cannot, and has speculated on a relationship between right-wing militias and drug traffickers.

This presidential election has led to unusually high levels of political violence, which continues to pose a threat. In a special report by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), its authors asserted that ‘Police militias and drug trafficking groups use violence to intimidate candidates who pose a threat to their activities.’ Two other NGOs have reported that compared to 46 instances of recorded political violence in 2018, when Bolsonaro was elected, the 2022 election has seen the figure so far hit 247—a 400% increase.

Former MP for Rio de Janeiro Roberto Jefferson, a Bolsonaro ally, was so furious with the decision by TSE Minister, Carmen Lucia, to vote for punishing Sao Paulo radio station for offensive comments on Lula that he posted a video slinging a string of insults at her, including ‘witch’, ‘prostitute’, and others much stronger.

The above mentioned Roberto Jefferson was arrested in 2021 as part of a clampdown on ‘digital militias’, which saw him placed under house arrest. When police went to his Rio home to take him into custody for breaking his confinement and the vicious attack on judge Carmen Lucia, he fired a rifle and threw grenades, and then proceeded to barricade himself in his house using other firearms and explosives for eight hours.

Though Bolsonaro condemned Jefferson’s actions, he repudiated the investigation that led to his house arrest. Lula tweeted: ‘[Jefferson] is the face of everything that Bolsonaro stands for.’

The manner of this liberalisation of firearm rules raises suspicions that ever since his election in 2018, Bolsonaro has been preparing to lead some kind of authoritarian outcome by non-peaceful means. It remains not implausible that if he loses this run-off, he may feel tempted to use violence to stay in power.

Military Tutelage

There is, as a result, huge concern about Bolsonaro’s repeated efforts to undermine democracy, specially about his persistent questioning of the trustworthiness of the electronic voting machines, which he has falsely suggested could be used to rig the election against him. His cabinet ministers, nearly half of whom are military generals, have also repeatedly questioned the election process.

There is great apprehension that sections of the military top brass may support Bolsonaro in an eventual rejection of the election results if he is defeated, not helped by persistent rumours that the military will have a ‘parallel vote count’ for the electoral process. This section of the military I refer to is unhappy with the TSE’s hard line in clamping down on bolsonarismo’s disinformation campaign. Hamilton Mourão, a retired army general, Bolsonaro’s vice president, and now elected senator for Rio Grande do Sul, shares this view. Mourão supported a Bolsonaro threat to increase the number of members of the TSE to reduce its vigour in fighting fake news. He even publicly attacked TSE judge Alexandre de Moraes for ‘overstepping his authority’.

Another General, Paulo Chagas, attacked the TSE as recently as 22 October for ‘conspiring in favour of the election of a convicted thief” (read: Lula). In April, General Eduardo Vilas Boas, special adviser to the presidency’s security cabinet, launched a similar attack against the TSE. And Bolsonaro’s vice-president and current running election mate, Walter Braga Netto, a retired general and former minister of defence, broached the view in July 2022 that without printed ballots, the 2022 election was unviable.

Worse, Braga Netto, with the commanders of the Navy, Army, and Air Force, signed a communiqué in March 2022 both celebrating the anniversary of the 1964 military coup d’état that ousted democratically elected president Joao Goulart, for ‘reflecting the aspirations of the people at that time’, and condemning those who depict the military dictatorship ‘as an anti-popular, anti-national and anti-democratic regime’.

Lula for Hope

In contrast to the terrifying atmosphere created by Bolsonaro, Lula brings a message of hope and intends to run a government that can overcome these four bolsonarista years. Lula stands on solid ground to make this promise.

The legacy of the PT administrations (2002-2016) is indeed impressive: 36 million Brazilians were taken out of poverty; the Zero Hunger programme guaranteed three meals a day for millions who had previously gone hungry; housing policies meant new houses for 10 million people in 96% of the country’s municipalities; 15 million new jobs were created; unemployment was 5.4%; the number of university students increased by 130%; spending on health increased by 86%, employing about 19,000 new health professionals giving healthcare to 63 million poor Brazilians; external debt fell from 42% to 24% of GDP; and Brazil played a leading and influential role in the world. And much more—no wonder Lula ended his government in 2010 with an 87% rate of approval.

Lula has placed himself at the head of a broad national coalition that defeated Bolsonaro in the first round, and has just made public a Letter for the Brazil of Tomorrow, which lays out key components of his government programme.

It includes policies on investment and social progress with jobs and good income, sustainable development and stopping the destruction of the Amazon, expansion of state expenditure on education, health, housing, infrastructure, public safety, and sports, upholding and promoting human rights and citizenship, re-industrialising Brazil, creating sustainable agriculture, restoring Brazil’s active voice in world politics, and the restoration and expansion of all freedoms currently curtailed and under threat to ensure their full enjoyment in a society organised against prejudice and discrimination.

The priority for his government will be helping the 33 million people going hungry and 100 million people thrown into poverty by bolsonarista misgovernment, both central elements in the strategic aim to reconstruct the nation.

In his Letter, Lula says that on 30 October, Brazilians confront a stark choice:

One is the country of hate, lies, intolerance, unemployment, low wages, hunger, weapons and deaths, insensitivity, malice, racism, homophobia, destruction of the Amazon and the environment, international isolation, economic stagnation, admiration of dictatorship and torturers. A Brazil of fear and insecurity with Bolsonaro.

The other is the country of hope, of respect, of jobs, of decent wages, of dignified retirement, of rights and opportunities for all, of life, of health, of education, of the preservation of the environment, of respect for women, for the black population and for diversity; of sovereign integration with the world, of food on the plate and, above all, of an unwavering commitment to democracy. A Brazil of hope, a Brazil for all.

Bolsonaro has made it abundantly clear that unless electoral fraud is perpetrated against him, he should win. On Thursday 26 October, four days before polling day, he called a press conference to denounce the alleged suppression of his electoral propaganda in radio stations in Bahia and Pernambuco. The TSE dismissed the allegation for ‘lack of credible evidence.’ The press conference occurred immediately after an emergency meeting with ministers and commanders of the three armed forces branches in which Bolsonaro announced his intention to challenge the TSE decision. This false allegation seems to be the ‘smoking gun’ he needed to ‘prove’ the election was stolen, if he loses.

Simply put, a hard-won democracy is once again on the brink. Only a Lula victory can pull it back from the abyss.

This article was first published in Tribune

About the Author

Francisco Dominguez is head of the Research Group on Latin America at Middlesex University. He is also the national secretary of the Venezuela Solidarity Campaign and co-author of Right-Wing Politics in the New Latin America (Zed, 2011).

]]>

Please read below the Brazil Solidarity Initiative’s urgent statement on the defence of Brazilian democracy and the electoral system in the face of growing political violence and threats of a far-right powergrab from Bolsonaro. The election takes place today (October 2nd.)

On Sunday 2 October, over 150 million Brazilian voters will elect the next president of one of the world’s largest democracies. The choice is between the far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro and progressive candidate Lula da Silva.

Polls show Lula has a strong lead in the polls and is on track to pass the 50% threshold needed to be elected in the first round.

Lula previously served as Brazil’s president after being elected as the country’s first working class leader earlier this century. When he left office in 2011 he had record-high approval ratings of 83 percent, the result of his government’s success in reducing poverty and addressing social inequality,

Lula was favourite to win the 2018 Presidential election until he was arrested and jailed on trumped-up charges orchestrated by powerful elites in Brazil and Washington.

That injustice opened the door to the election of Jair Bolsonaro, a strong supporter of Brazil’s past military dictatorship and under which he had served as a military officer.

In office, Bolsonaro has repeatedly undermined Brazil’s democracy and trampled on the rights of women, LGBT, Black & Indigenous communities and environmental activists.

The run-up to this Sunday’s Presidential election has been no different. Bolsonaro and his cabinet ministers, nearly half of whom are military generals, have baselessly sought to bring into question the integrity of the election process. They have suggested that the military should have a greater role in overseeing the election and have threatened to reject the results if Bolsonaro loses. Bolsonaro even told supporters that “If necessary, we will go to war” over the election results. While his son has called on the growing number of Brazilian gun-holders to become “Bolsonaro volunteers”.

Threats and a climate of hate whipped up by Bolsonaro and his allies have created a context of rising political violence against supporters of Lula Da Silva. There has been the killing of Lula supporters and Worker’s Party officials and attacks on pro-Lula marches.

We call on all progressives to be alert to the threats posed by Jair Bolsonaro to Brazil’s democracy and any attempts to prevent the peaceful transfer of power. We call on the UK Government to speak out against any efforts to incite political violence and undermine the electoral process and to review relations with any Brazilian government that comes to power through undemocratic means.

Please share the call for vigilance over the Brazilian election on Facebook and twitter. You can also read this urgent statement on the Brazil Solidarity Initiative website here.

]]>A few days ago, when neofascist candidate José Antonio Kast was winning the first round of the country’s presidential elections, Chile’s 2019 rebellion aimed at burying neoliberalism appeared to be at an end. However, it has been greatly reinvigorated with the landslide victory of the Apruebo Dignidad1 (I Vote For Dignity) candidate, Gabriel Boric Font, who obtained 56 percent of the vote in the second round, that is nearly 5 million votes, the largest ever in the country’s history. Gabriel, age 35 is the youngest president ever.

That result would have been greater had it not been for the policy of the minister of transport, Gloria Hutt Hesse, deliberately offering almost no public transport services, especially buses to the poor barrios, aimed at minimising the number of pro-Boric voters, hoping they would give up and go back home.2 Throughout Election Day, there were constant reports on the mainstream media, especially TV, of people in the whole country but particularly at Santiago3 bus stops bitterly complaining for having to wait for 2 and even 3 hours for buses to go to polling centres. Thus, there were justified fears they would rig the election, but the determination of poor voters was such that the manoeuvre did not work.

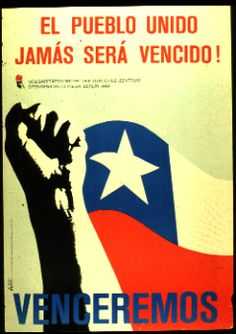

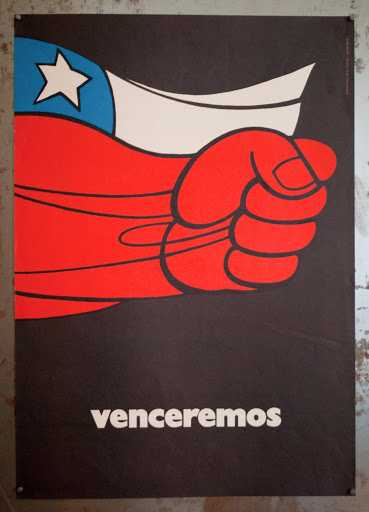

Kast’s campaign, with the complicity of the right and the mainstream media, waged one of the dirtiest electoral campaigns in the country’s history, reminiscent of the US-funded and US-led ‘terror propaganda’ mounted against socialist candidate Salvador Allende in 1958, 1964 and 1970. Through innuendo and the use of social media, the Kast camp spewed out crass anti-communist propaganda, charged Boric with assisting terrorism, suggested that Boric would install a totalitarian regime in Chile, and such like. The campaign sought to instil fear primarily in the petty bourgeoisie by repeatedly predicting that drug addiction – even implying that Boric takes drugs, crime, and narco-trafficking, would spin out control if Boric became president. Besides, the mainstream media assailed Boric with insidious questions about Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba, for which Boric did not produce the most impressive answers.

To no avail, the mass of the population saw it through and knew that their vote was the only way to stop pinochetismo taking hold of the presidency, and they had had enough of president Piñera. Their perception was correct, they knew that in the circumstances the best way to ensure the aims of the social rebellion of October 2019 was by defeating Kast and his brand of unalloyed pinochetismo.

As the electoral campaign unfolded, though Kast backtracked on some of his most virulent pinochetista statements, people knew that if he won he would not hesitate to fully implement them. Among many other gems, Kast declared his intention as president to abolish the ministry for women, same sex marriage, the (very restrictive) law on abortion, eliminate funding for the Museum in the Memory of the victims of the dictatorship and the Gabriela Mistral Centre for the promotion of arts, literature and theatre, withdraw Chile from the International Commission of Human Rights, close down the National Institute of Human Rights, cease the activities of FLACSO (prestigious Latin American centre of sociological investigation), build a ditch in the North of Chile (border with Bolivia and Peru) to stop illegal immigration, and empower the president with the legal authority to detain people in places other than police stations or jails (that is, restore the illegal procedures of Pinochet’s sinister police).

Kast’s intentions left no doubt as to what the correct option was in the election. I was, however, flabbergasted with various leftist analyses advocating not to vote, in one case because ‘there is no essential difference between Kast and Boric’, and, even worse, another suggested that ‘the dilemma between fascism and democracy was false’ because Chile’s democracy is defective. My despair with such ‘principled posturing’, probably dictated by the best of political intentions, turned into shock when on election day itself a Telesur correspondent in Santiago interviewed a Chilean activist who only attacked Boric with the main message of the feature being “whoever wins, Chile loses”.4

The centre-left Concertación coalition5 that in the 1990-2021 period governed the nation for 24 years, bears a heavy responsibility for maintaining and even perfecting the neoliberal system, expressed openly its preference for Boric, and assiduously courted support for im in the second round. Hence, those who believe there is no difference between Kast and Boric, do so not only from an ultra-left stance but also by finding Boric guilty by association, even though he has not yet had the chance to even perpetrate the crime.

This brings us to a central political issue: what has the October 2019 Rebellion and all its impressively positive consequences posed for the Chilean working class? What is posed in Chile is the struggle not (yet) for power but for the masses that for decades were conned into accepting (however grudgingly) neoliberalism as a fact of life, until the 2019 rebellion that was the first mass mobilization not only to oppose but also to get rid of neoliberalism.6 The Rebellion extracted extraordinary concessions from the ruling class: a referendum for a Constitutional Convention entrusted legally with the task to draft an anti-neoliberal constitution to replace the 1980 one promulgated under Pinochet’s rule.

The referendum approved the proposal of a new constitution and the election of a convention by 78 and 79 per cent, respectively in October 2020. The election of the Convention gave Chile’s right only 37 seats out of 155, that is, barely 23 per cent, whereas those in favour of radical change got an aggregated total of 118 seats, or 77 per cent. More noticeably, Socialists and Christian Democrats, the old Concertación parties, got jointly a total 17 seats. The biggest problem remains the fragmentation of the emerging forces aiming for change since together they hold almost all the remaining seats, but structured in easily 50 different groups. Nevertheless, in tune with the political context the Convention elected Elisa Loncón Antileo, a Mapuche indigenous leader as its president, and there were 17 seats reserved exclusively for the indigenous nations and elected only by them; a development of gigantic significance.

The mass rebellion also obtained other concessions from the government and parliament such as the return of 70 percent of their pension contributions from the private ‘pension administrators’, which rightly Chileans see as a massive swindle that has lasted for over 3 decades. This has dealt a heavy blow to Chile’s financial capital. A proposal in parliament for the return of the remaining 30 percent (at the end of September 2021) failed to be approved by a very small margin of votes. I am certain the AFPs have not heard the last on this matter.

The scenario depicted above suddenly became confused with the results of the presidential election’s first round where not only Kast came out first (with 27 percent against 25 for Boric), but which also elected Deputies and Senators for Chile’s two parliament chambers. Though Apruebo Dignidad did very well with 37 deputies (out of 155) and 5 senators (out of 50), the right-wing Chile Podemos Más (Piñera’s supporters) got 53 deputies and 22 senators, whilst the old Concertación got 37 deputies and 17 senators.

There are several dynamics at work here. With regards to the parliamentary election, traditional mechanisms and existing clientelistic relations apply with experienced politicians exerting local influence and getting elected. In contrast, most of the elected members of the Convention are an emerging bunch of motley pressure groups organised around single-issue campaigns (AFP, privatization of water, price of gas, abuse of utilities companies, defence of Mapuche ancestral lands, state corruption and so forth), which did not stand candidates for a parliamentary seat.

A most important fact was Boric’s public commitment in his victory speech (19 Dec) to support and work together with the Constitutional Convention for a new constitution. This has given and will give enormous impetus to the efforts to constitutionally replace the existing neoliberal economic model.

What the Chilean working class must address is their lack of political leadership. They do not have even a Front of Popular Resistance (FNRP) as the people of Honduras to fight against the coup that ousted Mel Zelaya in 2009. The FNPR, made up of many and varied social and political movements, evolved into the Libre party that has just succeeded in electing Xiomara Castro, as the country’s first female president.7 The obvious possible avenue to address this potentially dangerous shortcoming would be to bring together in a national conference, all the many single-issue groups together with all social movements and willing political currents to set up a Popular Front for an Anti-Neoliberal Constitution.

After all, they have taken to the streets for two years to bury the oppressive, abusive and exploitative neoliberal model, and it is becoming clearer what to replace it with: a system based on a new constitution that allows the nationalization of all utilities and natural resources, punishes the corrupt, respects the ancestral lands of the Mapuche, and guarantees decent health, education and pensions. The road to get there will continue to be bumpy and messy, but we have won the masses; now, with a sympathetic government in place, we can launch the transformation of the state and build a better Chile.

1 An electoral coalition of essentially the Broad Front and the Communist Party, with smaller groups.

2 In Chile voting is voluntary and the levels of abstention for the first round was 53 per cent; El País on Dec 17 reported that 60 per cent of the voters in La Pintana, a Boric stronghold, stayed home in the first round.

3 Santiago has over 6 million inhabitants of the 19 million Chilean total.

4 The leaders and presidents of the Latin American countries that make Telesur possible would fundamentally disagree with such an, in my view, irresponsible message.

5 The Concertación is made up essentially of the Socialist and Christian Democratic parties, plus other smaller parties, with the Socialists and Christian Democrats holding Chile’s presidency respectively for 3 and 2 periods out of a total 6.

6 The battle for Chile, https://prruk.org/the-battle-for-chile/

7 See my take on Honduras here https://prruk.org/honduras-left-wing-breakthrough/

By means of sheer resistance, resilience, mobilisation, and organisation, they have managed to defeat Juan Orlando Hernandez’s narco-dictatorship at the ballot box. Xiomara Castro, presidential candidate of the left-wing Libre party (the Freedom and Refoundation Party), in its Spanish acronym), obtained a splendid 50+ percent—between 15 to 20 percent more votes than her closest rival candidate, Nasry Asfura, National Party candidate, in an election with historic high levels of participation (68 percent).

The extraordinary feat performed by the people of Honduras takes place under the dictatorial regime of Hernandez (aka JOH) in an election marred by what appears to be targeted assassinations of candidates and activists. Up to October 2021, 64 acts of electoral violence, including 11 attacks and 27 assassinations, had been perpetrated. And in the period preceding the election (11-23 November) another string of assassinations, mainly of candidates, took place.

None of the fatal victims were members of Hernandez’s National Party. The aim seems to have been to terrorise the opposition, and particularly their electorate, into believing that it was unsafe to turn out to vote—and that even if they did, they would again steal the election through fraud and violence, as they have done twice already, in 2013 and 2017.

Commentators correctly characterise this as the ‘Colombianisation’ of Honduran politics—that is, a ruling gang in power deploys security forces and paramilitary groups to assassinate opposition activists. In Honduras, the most despicable act was the murder of environmental activist, feminist, and indigenous leader Berta Caceres by armed intruders in her own house, after years of death threats.

She had been a leading figure in the grassroots struggle against electoral fraud and dictatorship, and had been calling for the urgent re-founding of the nation, a proposal that has been incorporated into the programme of mass social movements such as the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH). Since 2009, hundreds of activists have been assassinated at the hands of the police, the army, and paramilitaries.

The Colombianisation analogy does not stop at the assassination of opponents. Last June, the Washington Post explained the extent of infiltration by organised crime: ‘Military and police chiefs, politicians, businessmen, mayors and even three presidents have been linked to cocaine trafficking or accused of receiving funds from trafficking.’

US Judge Kevin Castel, who sentenced ‘Tony’ Hernandez, JOH’s brother, to life in prison after being found guilty of smuggling 185 tons of cocaine into the US, said: ‘Here, the [drug]trafficking was indeed state-sponsored’. In March 2021, at the trial against Geovanny Fuentes, a Honduran accused of drug trafficking, the prosecutor Jacob Gutwillig said that President JOH helped Fuentes with the trafficking of tons of cocaine.

Corruption permeates the whole Honduran establishment. National Party candidate Nasry Asfura has faced a pre-trial ‘for abuse of authority, use of false documents, embezzlement of public funds, fraud and money laundering’, and Yani Rosenthal, candidate of the once-ruling Liberal party, a congressman and a banker, was found guilty and sentenced to three years in prison in the US for ‘participating in financial transactions using illicit proceeds (drug money laundering).’

The parallels continue. Like Colombia, Honduras is a narco-state in which the US has a host of military bases. It was from Honduran territory that the Contra mercenaries waged a proxy war against Sandinista Nicaragua in the 1980s, and it was also from Honduras that the US-led military invasion of Guatemala was launched in 1954, bringing about the violent ousting of democratically elected left-wing nationalist president Jacobo Arbenz. Specialists aptly refer to the country as ‘USS Honduras’.

So cocaine trafficking and state terrorism, which operates as part of the drug business in cahoots with key state institutions, is ‘tolerated’ and probably supported by various US agencies ‘in exchange’ for a large US military presence—the US has Soto Cano and 12 more US military bases in Honduras—due to geopolitical calculations like regional combat against left-wing governments. This criminal system’s stability requires the elimination of political and social activists.

Thus many US institutions, from the White House all the way down the food chain, turn a blind eye to the colossal levels of corruption. In fact, SOUTHCOM has been actively building Honduras’ repressive military capabilities by funding and training special units like Batallion-316, which reportedly acts as a death squad, ‘guilty of kidnap, torture, and murder’. ‘Between 2010 and 2016, as US “aid” and training continued to flow, over 120 environmental activists were murdered by hitmen, gangs, police, and the military for opposing illegal logging and mining,’ one report explains.

The legacy left by right-wing governments since the violent ousting of Mel Zelaya in 2009 is abysmal. Honduras is one the most violent countries in the world (37 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, with 60 percent attributable to organised crime), with staggering levels of poverty (73.6 percent of households live below the poverty line, out of which 53.7 percent live in extreme poverty), high levels of unemployment (well over 12 percent), and even higher levels of underemployment (the informal sector of the economy, due to the effects of Covid-19, grew from 60 to 70 percent). Its external debt is over US$15 billion (57 percent of its GDP), and the nation suffers from high incidences of embezzlement and illegal appropriation of state resources by this criminal administration.

The rot is so pronounced that back in February this year, a group of Democrats in the US Senate introduced legislation intended to cut off economic aid and sales of ammunition to Honduran security forces. The proposal ‘lays bare the violence and abuses perpetrated since the 2009 military-backed coup, as a result of widespread collusion between government officials, state and private security forces, organised crime and business leaders.’ In Britain, Colin Burgon, the president of Labour Friends of Progressive Latin America, issued scathing criticism of the British government’s complicity for ‘having sold (when Boris Johnson was Foreign Minister no less) to the Honduran government spyware designed to eavesdrop on its citizens, months before the state rounded up thousands of people in a well-orchestrated surveillance operation.’

To top it all off, through the ZEDES (Special Zones of Development and Employment) initiative, whole chunks of the national territory are being given to private enterprise subjected to a ‘special regime’ that empowers investors to establish their own security bodies—including their own police force and penitentiary system—to investigate criminal offences and instigate legal prosecutions. This is taking neoliberalism to abhorrent levels, the dream of multinational capital: the selling-off of portions of the national territory to private enterprise. Stating that the Honduran oligarchy, led by JOH, is ‘selling the country down the river’ is not a figure of speech.

It is this monstrosity, constructed since the overthrow of President Mel Zelaya in 2009 on top of the existing oligarchic state, that the now victorious Libre party and incoming president Xiomara Castro need to overcome to start improving the lives of the people of Honduras. The array of extremely nasty internal and external forces that her government will be up against is frighteningly powerful, and they have demonstrated in abundance what they are prepared to do to defend their felonious interests.

President-elect Xiomara’s party Libre, is the largest in the 128-seat Congress, and with its coalition partner, Salvador, will have a very strong parliamentary presence, which will be central to any proposed referendum for a Constituent Assembly aimed at re-founding the nation. Libre has also won in the capital city Tegucigalpa, and in San Pedro Sula, the country’s second largest city. More importantly, unlike elections elsewhere (in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia), the National Party’s candidate, Asfura, has conceded defeat. Thus, Xiomara has a very strong mandate.

However, in a region dominated by US-led ‘regime change’ operations—the coup in Bolivia, the coup attempt in Nicaragua, the mercenary attack against Venezuela, plus a raft of violent street disorders in Cuba, vigorous destabilisation against recently elected President Castillo in Peru, and so on ad nausea—Honduras will need all the international solidarity we can provide, which we must do.

The heroic struggle of the people of Honduras has again demonstrated that it can be done: neoliberalism and its brutal foreign and imperialist instigators can be defeated and a better world can be built. So, before Washington, their Honduran cronies, their European accomplices, and the world corporate media unleash any shenanigans, let’s say loud and clear: US hands off Honduras!

This article first appeared in Tribune.

]]>And this is a continuing problem: in recent weeks we have seen further attempts. The left has been successful in the regional elections in Venezuela but the US refuses to recognise the left’s victory. Instead Venezuela is suffering from a punishing raft of sanctions, imposed by Trump and maintained by President Biden. The sanctions, which amount to a blockade, are designed to inflict such damage on the economy that the people will be amenable to ‘regime change’. Such a result would be enormously damaging for the people of Venezuela, their self-determination and progress.

And US attempts to undermine and destroy Cuba continue. Recently the US has tried to mobilise demonstrations against the government in Cuba in an attempt to foment regime change. These have met with little support. Meanwhile, the Biden administration has so far left all the Trump-era sanctions in place. These powerful sanctions coupled with Covid have halved foreign currency inflows over the last two years, leading to shortages of basic goods with the goal of generating discontent.

But nevertheless Cuba’s anti-covid work goes from strength to strength. More than 81 percent of Cuba’s population of 11 million is fully vaccinated, and researchers are upgrading the Cuban vaccine to ensure protection against the new Omicron variant. This is the reality of the Cuban system that the US wishes to destroy – health security for its people, not to mention the health solidarity that we have seen Cuba extend to other countries.

Given the amount of effort that the US puts into destabilising socialist governments and progressive advance in Latin America, it is not surprising that at times there have been victories which have been reversed or overthrown. But what we see is that the reversal is never accepted, whether in Bolivia or most recently Honduras, where the people have organised and fought back until victory. Bolivia recently celebrated the first anniversary of reversing the coup which took place against Evo Morales in 2019. The 2020 election saw a landslide victory for the MAS candidate after a year of brutal repression and neoliberal hardship. The process has taken longer in Honduras, but the coup in 2009 against Manuel Zelaya has now been reversed with the recent glorious victory of Castro, after 12 terrible years of neo-liberalism. Now Honduras will begin the process of building a democratic socialist society.

Of course there are many other examples across Latin America of imperialist intervention, and the common theme over decades has been western determination to introduce neoliberal economic policies to allow unfettered exploitation of the people and their economic resources. Indeed we can say that Latin America has been a testbed for neoliberal policies which have for decades been the main weapon for destroying socialism and for advancing US interests across the globe.

There has of course been repeated rejection of neoliberalism, Argentina is a powerful case that comes to mind, but when the US fails to impose its economic policy prescriptions it resorts to other means. Military intervention and war is one such method, but in Latin America the US has perfected a whole range of methods, from political intervention in elections, to lawfare and its use to conduct coups against legitimately elected representatives of the people.

Struggles on this front still continue – in Ecuador, for example, with the lawfare coup against Correa, but the left is still a huge force and I have no doubt that it will recover and prevail.

Brazil’s election next year is of the utmost importance globally. At the minute it is looking like Lula versus Bolsonaro and the US will do everything it can to support Bolsonaro. Lula is ahead and we must do everything possible to support his re-election. His victory will change geopolitics significantly for the better – whether it’s climate change, or increasing multipolarity. Brazil is an economic power house and it can once again be a political power house for the left.

Many of us will have been directly involved in one of the great initiatives of the Brazilian Workers Party – the World Social Forum, founded in Porto Alegre and backed by the city’s PT government, twenty years ago. 12,000 people attended that first meeting from around the world, organising and discussing alternatives to neoliberalism, and for a globalisation from below. That was a moment of transformation not only for the movement internationally but for Brazil, leading eventually to the electoral victory of Lula. No wonder the Brazilian elite and its US allies worked to drive him out of politics, but those malign forces will be defeated.

It is that kind of international cooperation, that emerged from Porto Alegre, that we need to regain, to re-empower ourselves as an international movement. A fighting movement, like the movements in Latin America, that don’t lie down when faced with coups, lawfare, economic warfare, military intervention, but re-organise and win.

We must stand together with the forces of progress internationally, get ourselves united and organised to challenge our own ruling class and the imperialist role it plays across the world. There is nowhere better to look to for lessons, guidance and inspiration than to our comrades in Latin America.

This is the text of a speech delivered at the Latin America conference in London on 4th December, 2021

]]>Giorgio Trucchi writes: Honduras is at the most important crossroads of its recent history.

On November 28, more than 5 million Hondurans will be asked to elect the President of the Republic, 128 deputies to the National Congress, 20 to the Central American Parliament, 298 mayors and more than 2 thousand municipal councillors.

As the election date approaches, the political atmosphere has become polarized, conflict has intensified and social tension grown.

No one has forgetten the violent repression of 2017 against those who protested against the gross electoral fraud that prolonged the agony of the current government regime. At that time, more than thirty people lost their lives violently and these crimes have remained in total impunity.

The bloody events of the last few days reawaken the ghosts of that violence and repression.

On November 11, a Liberal Party candidate for councillor, Óscar Moya, was shot several times in Santiago de Puringla (La Paz). Two days later the mayor of Cantarranas (Francisco Morazán) and candidate for reelection for the Liberal Party, Francisco Gaitán, was assassinated.

The following day the leader of the opposition Libertad y Refundación (Libre) Party, Elvir Casaña, and a Liberal Party activist, Luis Gustavo Castellanos, were killed in San Luis (Santa Bárbara) and San Jerónimo (Copán), respectively. Two other activists were wounded in the deadly attack on Castellanos.

On November 15, another attack killed Dario Juarez, a Liberal Party vice-mayor candidate in the municipality of Concordia (Olancho). Two days later, unknown persons made an attempt on the lives of Héctor Estrada, independent candidate for mayor of Campamento (Olancho) and Juan Carlos Carbajal, candidate for mayor of El Progreso for the Salvador Party of Honduras.

According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Honduras and the National Violence Observatory (ONV) of the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), more than 30 violent deaths have been registered in the context of the current electoral process, which is shaping up to be even more violent than that of 2017.

The Observatory reported at least 64 cases of electoral violence up until October 25, including 27 homicides and 11 attacks. To these must be added the most recent attacks that took the lives of five people in five days (as detailed above) and other non-fatal attacks.

The OHCHR condemned these acts of electoral violence “that affect the right to political participation” and urged the authorities to carry out “prompt, thorough and impartial investigations”.

A legacy of impunity

“These murders of local leaders are a prelude to what could happen during and after the elections. Let us remember that all this is happening after the approval in Congress of reforms and laws that deepen the criminalization of social protest and citizen mobilization,” warned Bertha Oliva, coordinator of the Committee of Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras (Cofadeh).

“They have been practically legalizing repression against those who demonstrate their discontent and defend human rights. These are the results,” she added.

In 2017, repression against those protesting the electoral fraud orchestrated by the ruling National Party claimed the lives of 37 innocent victims (Cofadeh 2018). Of all these cases only one was successfully prosecuted and the charges against the police officer accused of shooting and killing were dismissed.

“The chain of command was never investigated, nor the context in which these deaths were caused. The dictatorship gave the military police guarantees of impunity to capture, torture and execute opponents in the streets. This only generates the conditions for similar and even more violent events to be repeated”, predicted the human rights defender.

In this sense, Cofadeh will be monitoring and denouncing any electoral crimes committed before and during Election Day, as well as violations against people exercising their right to vote.

Three for the presidency

Of the 16 presidential aspirants, only three have a real chance of winning: Xiomara Castro of the opposition Libre Party, who leads most polls; Nasry “Tito” Asfura Zablah of the National Party, main opponent of the former first lady and Yani Rosenthal of the Liberal Party, representing the other traditional party in Honduras but with little chance of victory.

For Xiomara Castro, this is her second attempt to reach the presidency of the country, after the allegations of fraud around the questionable defeat she suffered in 2013 at the hands of Juan Orlando Hernandez.

After the public presentation of her “Government Plan to Refound Honduras 2022-2026”, Castro and Salvador Nasralla (of the Salvador Party of Honduras) formed an alliance, joined by the Innovation and Unity Party (Pinu), some sectors of the Liberal Party and an independent candidacy. In order to join efforts and potential votes, Nasralla renounced his presidential candidacy and supported Libre’s candidacy.

Nasralla, an eccentric, well known sports talk show host, was the 2017 presidential candidate of the Opposition Alliance against the Dictatorship, which also included Libre and Pinu and which received the support of a wide range of social, popular and union organizations.

On that occasion, the Alliance denounced the unconstitutionality of a new candidacy of Juan Orlando Hernández, since in Honduras the Constitution prohibited presidential reelection. The Alliance also mobilized for weeks against the electoral fraud that deprived Nasralla of the presidential seat, with the tacit consent of the United States, the European Union and the OAS.

“Tito” Asfura, popularly known as “Papi a la orden”, has been mayor of Tegucigalpa for two terms (2014-2022) for the ruling National party. A businessman with more than 30 years occupying governmental and legislative positions, he was a shareholder of an offshore company in Panama while still a public official. In the end, the said company ended up under the control of Banco Ficohsa, owned by the powerful Atala Faraj family.

In June of this year, the Court of Appeals suspended a pre-trial hearing against Asfura for abuse of authority, use of false documents, embezzlement of public funds, fraud and money laundering. In order to reactivate the hearing, the Superior Court of Accounts will have to carry out a special audit on the funds investigated by the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

According to information published in recent days, the former mayor of Tegucigalpa has also been linked to the notorious “Diamante” corruption case involving the mayor of San José, Costa Rica, Johnny Araya, who is being investigated by Costa Rican authorities for alleged bribes in exchange for public works.

The third candidate is former congressman and banker Yani Rosenthal, who in 2017 was indicted and sentenced to three years in prison in the United States for participating in financial transactions using illicit proceeds (drug money laundering). He voluntarily turned himself in and was held at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York but returned to Honduras in mid-2020.

Both the investigations carried out by US prosecutors and the media Pandora Papers investigation revealed the connection between the Rosenthal family, one of the richest in the region, and several offshore companies that may have been used to launder money.

Programs and proposals

In her government program, Xiomara Castro points out the need to rebuild the democracy broken by the 2009 coup and to re-found the country through a Constituent Assembly that “gathers all sectors to agree on the legal bases of their future coexistence in a new consensual order”, leading the nation towards the construction of a democratic socialist state. While, by contrast, both Asfura and Rosenthal propose the same worn out neoliberal recipes that have led Honduras to be among the poorest and most unequal countries of the continent.

“Xiomara proposes a government of national reconciliation that includes all sectors of the opposition. A government that aims to overcome these disastrous years that have deepened the neoliberal model, privatizing services, ceding national territory, handing over public goods, expanding extractivism, putting national sovereignty up for sale,” said Gilberto Ríos, candidate for congressman for Libre.

The social movement leader explained that Libre’s government plan proposes to move from a deeply oligarchic State to a democratic socialist one. Among many other points, it intends to repeal all those laws and reforms approved by the dictatorship, which deeply harm the interests and rights of the immense majority of the Honduran population.

Thus, we are talking about, among others, the Hourly Employment Law that deepens labor insecurity and annuls the rights of workers, the Secrecy Law that blocks public auditing of State funds, as well as the Surveillance Law that allows spying on the political opposition and too the Organic Law of the Economic Development Zones (ZEDEs) that violates national sovereignty. It is also expected to reverse reforms made to the Penal Code that criminalize social protest and mobilization.

“It will be a more redistributive government, of social works and projects, that defends human rights, consistent with the needs and security of the population. In this sense – clarified Ríos – we differentiate ourselves from the other candidates and political parties because they are openly neoliberal and represent the interests of the Honduran oligarchy, transnational capital and the old bipartisanship. That is what it is all about: defeating the traditional bipartisanship and neoliberalism”.

How is Honduras now?

The Central American country arrives at these elections in difficult conditions, to put it euphemistically.

Honduras currently ranks among the most unequal countries in Latin America, with 62 percent of the population mired in poverty and almost 40 percent in extreme poverty (EPHPM 2020). According to a recent report by the National Institute of Statistics (INE 2021), removed from the institution’s website twelve hours after its publication, in July 2021 poverty had reached 73.6 percent of the population.

That increase is also the result of disappointing government management in the face of the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and the two hurricanes that struck the country last year.

According to figures from the Technical Unit for Food and Nutritional Security (Utsan), 1.3 million Hondurans face food insecurity and almost 350 thousand people are in a “critical situation”. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate has reached 10% of the economically active population (EAP), perhaps the highest in the Latin American region. There are at least 4 million Hondurans with employment problems and more than 700 thousand unemployed workers.

Faced with this scenario, thousands of families have taken irregular migration as their only option, the vast majority of whom are being held up at the borders. It is a portrait of one of the deepest tragedies of the last 40 years.

“In the last ten years Honduras has had a frank deterioration, not only in the rule of law in general, in democratic institutionality, in the population’s access to basic services and in the fight against poverty, but also socio-economically. When one looks at all these indicators, one realizes that rather than a failed state, we should speak of a dead state,” said Ismael Zepeda, economist at the Social Forum on Foreign Debt and Development of Honduras (Fosdeh).

Currently Honduras’ public debt exceeds 70% of GDP: the country’s economic growth is concentrated mainly in three sectors: financial, energy and telecommunications.

“These are sectors that do not produce development, nor do they generate redistribution, rather they produce more concentration of weath. In addition, we have an army of more than 250,000 public employees who absorb almost 50% of the budget, while there is a worrying drop in revenue. The situation is unsustainable and will represent a very heavy burden for whoever wins the elections”, explained Zepeda.

For years, the National Party has maintained a supernumerary staff, mainly composed of party activists. In practice, it has plundered the State so as to employ its political leaders and create client networks so as to stay in power.

State reengineering

For the Fosdeh economist, an immediate reengineering of the government, a reconversion of the productive system, a fiscal pact to dynamize the economy and efforts towards progressive taxation are necessary. Likewise, it is imperative to guarantee transparency, accountability and the fight against corruption, while promoting a strategy of internal and external debt reduction.

Finally, the generation of decent jobs, the creation of programs that prevent the deepening of poverty, more equitable management and redistributive policies to reduce social inequality, are also key elements the new government must implement.

“When a country is mired in a multiple crisis and has badly deteriorated, it is easy, so to speak, for a candidate to make promises. The most important thing, then, is not so much what is offered, but the way in which things eventually get done”, concluded Zepeda.

Labor insecurity

The 2009 coup d’état in Honduras not only broke the institutional framework and strengthened the oligarchy and elite power groups, but also allowed the governments that followed the coup to deepen the neoliberal extractivist model, encouraging the plundering of national territory and public wealth and increasingly deregulating the labor market.

For Joel Almendares, secretary general of the United Confederation of Honduran Workers (CUTH), the impacts of these policies on labor and union rights have been devastating for the vast majority of the population.

“There has been a growing deregulation of labor, coupled with the deepening of labor flexibilization and insecurity. One of the most nefarious laws has undoubtedly been the Hourly Employment Law: rights have been lost and permanent jobs have been made precarious,” said Almendares.

“There were also companies or institutions that simply changed their name or corporate name and did away with unions. Others created parallel unions to counteract a genuine organizing process,” he added.

Regression

All of these anti-worker measures have negatively impacted the safeguarding of rights.

“There are clear setbacks in the right to free unionization and collective bargaining. The programs to generate employment have been a mockery, tailored to the interests of large transnationals. Juan Orlando Hernández has definitely been a disaster for the labor and union sector”, stated the CUTH general secretary.

Another factor contributing to the deepening of the crisis has been the behavior of the government’s labor authorities.

“Shielding themselves behind the need to generate employment and supposed development, they have been biased and have systematically protected the interests of big national and transnational capital. They have done so at the expense of the rights of workers, abandoning them and allowing the violation of their rights. They have not protected them, and have been their executioners instead,” he lamented.

In view of this situation, the CUTH presented the Libre candidate with the political proposal of the union sector where, among other points, it calls for the immediate repeal of the above mentioned laws, to put a stop to outsourcing and labor insecurity, and to guarantee respect for the Teachers’ Statute and the ILO conventions[1].

The cancer of corruption

On November 17, the feature film “At the edge of the shadows” (you can see it here) was released in a movie theater in Tegucigalpa, a documentary that reflects the web of corruption, impunity, territorial dispossession and violence experienced by the Honduran people, forced to confront perverse plans that operate from the shadows.

Luís Méndez, member of the collective ‘La Cofradía’ that made the documentary, explained that the objective of the work is precisely to show citizens how corruption networks are formed and how they are articulated to involve politicians, public officials, national and transnational economic groups in a way cutting across all society.

The documentary addresses four crucial areas: the looting of Social Security and the health crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the dispossession of territories and pubic wealth, the co-optation of the justice system and its collusion with corruption, organized crime and the criminalization of protest. The fourth area has to do with the concept of democracy in a context as broken as the Honduran one.

Through key characters and experts, and with the participation of the current head of the Specialized Prosecutor Unit against Corruption Networks (Uferco), Luis Javier Santos, to tie up loose ends, the film rocks the country’s foundations, shaking up the conscience of the people, showing how Honduras is controlled by a criminal network that has ruled since the 2009 coup, and has become entrenched in the state apparatus.

“The documentary provokes disappointment, anger and rage, but also leaves the feeling that we are not defeated, that it is possible to fight, as many organizations and people do from the territories and cities.

In the midst of so much State violence, in the midst of a State held hostage – continued Méndez – there is resistance and struggle. As Berta Cáceres said, our peoples know how to do justice and they do it following their own trajectory, from their resistance, from their struggle for emancipation”.

Enough is enough!

A few days before the elections, the Convergence against Continuity, a platform made up of several organizations and personalities, made a public statement and recalled that these elections “are being held in a context of narco-dictatorship, whose creators came to control the State by violent and unconstitutional means and are not willing to hand over power by democratic political means”.

In this sense, the Convergence ratified its repudiation of “the mafia led by Juan Orlando Hernandez” and warned of the possibility that, in view of an imminent defeat, “he may orchestrate a new and violent electoral fraud by manipulating the voting process and vote counting”.

Finally, they made a vehement call to the Honduran people to “mobilize massively to the polls” and defend their vote “from these anti-democratic machinations”.

They also urged them to punish with their vote “the criminal group that has hijacked the State” and to vote for those candidates “who have shown firm signs of being against the narco-dictatorship, of fighting against corruption and for the defense of national sovereignty”.

Violence against human rights defenders

Several international reports, including “Last Line of Defense” published this year by the British organization Global Witness, point to Honduras as one of the most dangerous places in the world for human rights defenders, especially for those who defend land and common wealth.

The emblematic cases of the murder of Berta Cáceres, the disappearance of the Garífuna activists of Triunfo de la Cruz and the illegal imprisonment of the eight water and life defenders of Guapinol are a clear example of what is happening in the country.

The use and abuse of the justice system and the collusion of the State with extractive companies are two of the elements that characterize the systematic violation of human rights in Honduras.

According to Global Witness, in 2020 at least 129 Garifuna and indigenous people suffered attacks for opposing extractive projects and 153 defenders have been murdered in the last decade. In addition, the Center for Information on Business and Human Rights (Ciedh) points to Honduras as the country with the most judicial harassment against human rights defenders.

The situation of women and LGBTI people is also dramatic.

The Women’s Human Rights Observatory of the Women’s Rights Center (CDM) reports that in the first five months of the year, the Public Ministry registered a total of 1,423 complaints of sexual crimes (9.5 per day). Of these, 1,238 were attacks against women (8.1 per day) and 63.4 percent (785) were against minors. These data confirm that in Honduras a woman or girl is sexually assaulted every 3 hours.

In the last ten years, 4,707 women have been murdered in Honduras. 710 were killed in the last two years (2019-2020) and 301 women were victims of femicide up until November 15 of this year. Impunity is practically absolute.

According to the Observatory of Violent Deaths of the Catrachas Lesbian Network, in just over 12 years 390 LGBTI people have been murdered, 17 so far this year. Ninety-one percent of the cases remain in complete oblivion and impunity. Only 9 percent of perpetrators are convicted.

In recent months, a large and representative group of women’s and feminist organizations held a discussion with Xiomara Castro to present their demands and proposals. The activity led to the signing of a ‘State Pact’, the content of which will be implemented if Xiomara is elected as the first woman president of Honduras.

Similarly, in her government plan, Xiomara pledged to implement public policies safeguarding the existence and guaranteed access to fundamental human rights for LGBTI people (p.64).

Voting against the dictatorship

The Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (Copinh) added its voice “in moments of the battle for survival in the face of the maximum expression of dispossession, fear and violence in the history of our country under a de facto and authoritarian government.”